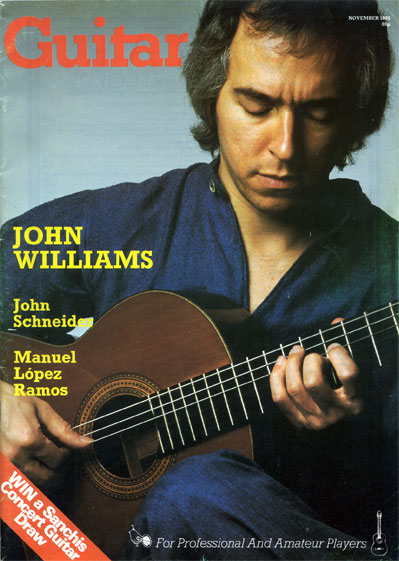

John Williams

interviewed in 1983

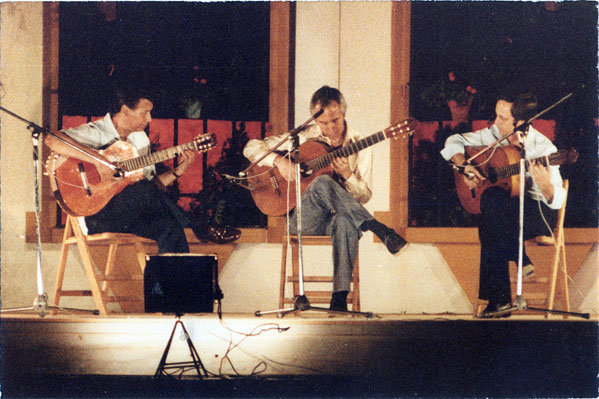

John’s two-week classical guitar course at Paco Peña’s Encuentro Flamenco is described in [Guitar, Nov 1983]. The following conversation took place, in a congenial atmosphere of sun, señoritas and sloth, at the end of it.

How do you come to be doing this course with Paco?

I knew about it two or three years ago when Paco started it; he’d been thinking quite a lot about it in London, because he wanted to do it very much, in such a way that everyone in Córdoba would co-operate and it would grow into something very important in the city. I felt that it was an important thing for him, actually to do it, and in a sense I was already bound up with the enthusiasm of it through hearing him talk about it, so when he finally asked me if there was a chance that I would come, if I remember rightly, I half-invited myself—being friends can sometimes be a little difficult when it comes to ‘official’ invitations.

So it was really a sort of foregone conclusion that if I did come I would do a course of some kind, and that during the stay I would play a concert.

You seem to have had very clear ideas about what you wanted to do with the course.

Yes. Luckily Paco wanted me to have a free rein, and over the last few years I’ve developed quite a lot of specific ideas about class teaching—so-called ‘Master Classes’, although I’m not very keen on the term; and my attitudes to beginners’ and children’s teaching are also becoming much more crystallised, not that those affected this course directly.

I decided, as I’ve done before in previous courses, that I wanted to concentrate on Baroque music and the influences of the pre-Baroque (the Renaissance, if you like); and on contemporary and ensemble music—leaving out that vast, wonderful, colourful repertory of the 19th century, and to a large extent the repertory of the 20th, let’s say the Romantic, Impressionist and Nationalist schools.

The reason for this is that over twenty years of teaching experience, I’ve come to be much less critical of other players, of whatever standard, when they’re playing Romantic or Impressionist music: much less critical in the sense that there are many ways that I like (or dislike) to play various pieces of music, but less and less where I can honestly say that someone is doing something right or wrong. The music is subjective in its expression, thereby the term Romantic; I find it difficult to say with conviction to someone, you shouldn’t play the middle part of Sevilla like this, however that might be. This attitude of mine connects very strongly with the way that I like to hold the class, which is (as much as possible) as an open discussion.

For this reason the music of the Baroque and pre-Baroque periods (and it’s a question of both musical and technical style, which is very, very interesting for guitarists); the world of contemporary music, with all the implications of the dynamics and musical systems involved; and ensemble music; these three categories afford the most constructive use of the opportunity of having a class. And all three, of course, lead to constant useful talk, criticism, and to-and-froing in the conversation.

Do you see a relation, then, between contemporary music and Baroque music, in that they both allow more freedom to the performer than that chunk of music in the middle?

I do, actually, and that attitude applies to all three categories; because it’s my personal view that the guitar has come at a very critical time in the history of our Western European musical culture. There are a lot of cultural and social parallels between all the popular forms of music today, and the music of the Renaissance or even the Baroque period, because both are ensemble, communal music. And these connections are not only musical and social/cultural, but funnily enough, they’re technical: this is one of the delights I’ve found over the last five years, as my own nose was rubbed in it by experience.

So much of the problem in the playing of Baroque music (and this is one of the main things, you’ll remember, we talked about in the class) is recapturing the style of that whole world of dynamics: of notes inégales, so-called double-pointées (double-dotting), the styles of the dances, the Allemandes, the Courantes, the French Overture, the methods of playing continuo… all these have great importance and interest for us as guitarists.

What I’ve realised over the last five years, is that all the interest we’ve been giving it has been almost solely directed to copying, and relating to the guitar, all the methods of ornamentation and dynamics of the harpsichord school; but in the process we’ve completely forgotten, although we know the lute was a Baroque instrument as well, that all these systems of playing unequal notes derived from the techniques of Renaissance and mediæval lute-playing! The techniques of inégales and all that were built into the way they played with the right hand, using thumb and forefinger for single-note passages. All the discussion that the harpsichordists have had to have on recapturing style through the use of inégales, is an effort to recapture by musicological study what the early lute-players did without thinking!

What has become for me really fascinating is that all the forms of popular music today, as played on the guitar, have that same built-in dynamic: either through finger-picking with the thumb and fingers, or most common of all (whether in blues, rock or jazz), through the use of a plectrum, which is down and up, a built-in difference of dynamic in alternate notes. Flamenco players have it too in the use of the thumb for rapid bass falsetas (alzapúa), and in their rasgueados (although not of course in their scale passages, which are like classical scales). So that overall the question is one that’s come to fascinate me, and it’s one that I’ve devoted a lot of time to in the class; and it got to be really lively, with half-a-dozen people who were very vocal in their ideas.

How far do you think the quest for authenticity can take us? How healthy is it that we should be trying to do exactly what John Dowland did four hundred years ago?

I’m not an expert on the period (although I’ve tried to learn as much as possible simply as a guide to the spirit of the music). I think that authenticity from that point of view is of crucial importance in knowing what one may do, not what one should do. I believe that musicians of all periods have always differed among themselves. I don’ think there was ever one magnificent age, whether Dowland’s, or Rameau’s, or Bach’s, when all the musicians agreed on an authentic style for their time, and we only have to find that out before we’ve got the magic way of playing today; because people varied then like they do today, and as they always will, thank God.

But I believe that research into old styles—and particularly the techniques, the technical limitations or otherwise of the instruments themselves—is always the best guide as to how the music sounded.

Now that’s not necessarily the best guide as to how we should make the music sound today, because we may find, in some cases, that there were limitations in those days that they were trying to get over. I’ve talked to people who are really immersed in that period, who really know it in their fingertips, like Anthony Rooley and Jim Tyler. My impression is, that their attitude is one of such vitality and enjoyment, everything they’ve learned is put at the service of bringing the music to life, not simply copying every tiny piece of ‘authenticity’ detail for detail.

The reason I ask is that there was a folk group called the New Lost City Ramblers who devoted themselves to rediscovering the ethnic American folk music of the 1920s and ’30s, and dug out lots of recordings and learnt them note for note. And the genuine old-time musicians that were still alive from that period, when they heard them, had tremendous respect for their scholarship and dedication, but they were astonished that the NLCR should want to play what anybody else played note for note, instead of doing their own thing.

I think that’s a good example, and you could apply that to other areas of playing, not just the notes but the dynamics. In fact I had that in mind when I was talking about copying the whole 18th century keyboard style of notes inégales and all that: we get caught up on the guitar trying to do that note for note, without realising that they were actually, as I said before, recreating something that was quite unconscious and natural in the lute era.

Musical fashions come and go, don’t they, although nobody admits it: for example, you never hear Mozart’s arrangement of Messiah now, everybody’s playing from Handel’s autograph scores. Do you think there’ll come another wave and people will lose interest in being authentic?

I don’t think so, not in that way, because authenticity has now come full circle for the periods in question. Take Bach’s violin suites, for instance, rediscovered in arrangements and editions by Schumann, Brahms and other 19th century violinists. All these made changes in the texts, for instance in the Chaconne, which we spent a lot of time on in the class. But now we’ve gone back to Bach’s original notes, and what we have found in that case is that it completely mirrors, technically, what we know about the instruments. The violin, for instance, of Bach’s day—all the old violins, Stradivarius, the whole lot, were all changed in the 19th century. Violinists know this, but a lot of other instrumentalists don’t realise it. This affects the style of playing; but technically and musically, we now know what was the original, and we know what were the reasons for it: we can see that it gave a more expressive, richer, more rhythmical, expression of the music, and that the 19th century manner, supposedly more romantic, was in fact a dead weight. I wasn’t anything like as expressive as the original, through misconceptions about reading the time and the instruments and the technique.

So in that way, with that period, we’ve come full circle. But I think on the guitar we have to go a little further back. We’re very lucky, because although the lute is not our instrument we can claim it as a relative, with a bit of the same popular liveliness; and we can save ourselves a lot of trouble if we just go straight back to that.

What do you think of the way the guitar is being taught these days?

I personally don’t have a lot of experience of the actual teaching at beginner level; All I see is the products of it (I keep in touch as much as possible, obviously, through students and other players). But my feeling, from watching first-year students at college, to advanced students, to professionals, has come to be that the basics of our teaching are actually wrong, and I feel very strongly about that now. And this is the reason, I think, that every time we have a comparison—at a supposedly comparable standard of playing—between a guitarist and another instrumentalist, there is a musical gap which is absolutely enormous. For example, in a competition where a guitarist is competing with other instrumentalists—violinists, pianists, flautists, whatever—he or she may be a finalist, or even a winner. But when it comes to very ordinary single-line phrasing, of tunes that are not particularly difficult: not only are they not as good as their peers on other instruments, in my experience they are nowhere near as good as everyone else in the competition. You can have forty people in an average music competition, with maybe three guitarists. And the best of those may be judged in the top half-dozen of the lot; but he will not be able to phrase, quite simply, a single line as well as the other thirty-seven. This is very common, to anyone that really listens.

You presumably, don’t feel, then, that this is because the guitar has only recently arrived on the scene as a serious instrument?

No, I don’t think it’s anything to do with that—the people concerned have been playing the same length of time! The reason you gave may be why its teaching hasn’t been sorted out properly, but in itself it’s not the reason that people don’t phrase properly.

My feeling is that guitar teaching—I know some people are aware of this, but I’m talking about the general approach now—the awareness of this in guitar teaching has not gone to the sufficient length of completely re-appraising instruction at the beginner’s level, whether with schoolchildren or adult amateurs.

The guitar is a string instrument, not a hybrid, not a cross between a violin and a harpsichord or piano, by virtue of one simple and important factor: we have to coordinate two hands to make a note. Before we do anything else we must learn to phrase; which means not just musical phrasing but thinking in terms of tone-colour, and how we make the note, just like a violinist does when he starts off. We don’t do that: we start with a few right-hand arpeggios and a couple of scales, and after a few weeks Hey Presto! we’re playing a simple little Carcassi study, or Carulli, or whatever. Straight away we’re in the deep end, not only in coordinating two hands but chords juxtaposed with arpeggios, scales, legatos, etc. etc. And frankly, it’s ridiculous. Because we’re doing that, with all the technical difficulties and limitations, without ever having developed in our fingers the ability to feel, and play, and phrase, a single melody line.

The proof of that is what actually happened in the class here: I brought a vast amount of early consort material, recorder ensemble music—all easy single-line stuff—involving both sight-reading and phrasing. We had the most advanced people in the class playing it. But even when they’d got over their sight-reading problems (which were pathetic), we were left with phrasing that was nonexistent.

And I understand that, I understand it for what it is: an example of the way in which the whole development of our technique is based around too many complex structures, which we can’t handle. Bits of chord-playing, of harmony-playing, of arpeggios, of scales, all hand-in-hand from the second or third week, at the expense of concentrating on the simple, beautiful, controlled melodic line. I feel there has to be a revolution—it’s not too strong a word—in guitar-teaching.

So how that’s to be done in practice, at the moment I’m not qualified to say. I need to talk with two or three well-qualified teachers who have a lot of direct experience and whom I trust a lot. I also want to open that subject up for discussion when I’m doing classes. But at the moment I’m deeply convinced of this, from talking with very good friends who are great musicians on other instruments, about how it honestly affects them when the guitarists play. It’s the unspoken Achilles heel of the guitar world.

This whole area has been the subject of a lot of attention in the last few years, especially from people like John Gavall, who have put a massive amount of effort into studying these things, and what is the best method. One considerable area of controversy seems to be whether a uniform system of guidelines should be imposed, because it’s felt that this takes away the teacher’s freedom to teach as he thinks best.

Yes, but to say that teaching should be conducted with regard to single-line phrasing before other elements predominate—that’s not really a guideline, that’s a general principle with which you agree or disagree. Once you agree, there can be many ways of putting it into practice.

I’m very glad you mentioned John Gavall, incidentally, because I first came across him in the late ’50s, when Gordon Crosskey moved up and taught for the West Riding County Council, under John Gavall, as a peripatetic guitar teacher. We had a lot of discussions, and I was very influenced then, without being as conscious as I am now of the importance of what he was doing. He was in fact one of the very first—maybe the first—to become aware of the importance of early teaching and to couple it with the point which I now want to make: which is ensemble playing. Because not only his direction of teaching (which was based around a lot of ensemble playing in school) but a lot of his published arrangements, for two, three or four guitars, have reflected that: comparatively easy single lines played ensemble with others, in exactly the same way that children learn to play recorder in school. They learn solo recorder pieces, but these are a supplement to a basic diet of recorder ensemble.

Personally, I would see the guitar in that light when it comes to teaching schoolchildren. The idea of a child having an individual private lesson, at school, once a week with an outside teacher is ridiculous. It means that the music is divorced from activity with other children; and in addition, at the moment, learning in this absurdly difficult way which is preventing the child not only from playing, but from developing a feeling for melodic line.

In addition, of course, ensemble playing has the not inconsiderable benefit that it accustoms the child gradually to stage-fright, instead of suddenly dumping him in front of an audience as a soloist.

Yes. Absolutely right. A whole lot of the attitudes and ethics of solo players stems from that, just as you put it. There’s none of that feeling of mutual confidence that one gets in a group. It’s as if you’re being trained from the age of eight to be a solo guitarist, it’s ridiculous. It doesn’t happen on any other instrument—well maybe the piano to some extent, but then the piano has the same problems. (They’re saved by an enormous repertory, which includes a lot of chamber music when they get good enough. But kids have to go home and have a piano lesson and practise after school, instead of doing it with other children at school.)

So in summary, as to teaching beginners, whether adults or children, there are two things: learning how to play and feel, tonally, a melody line—and combining that with ensemble playing. That’s really what art is, to communicate with other people, and we’re forgetting that.What did you think (apart from what you’ve already said) about the standard of the students on this course?

Initially I was a bit disappointed. We didn’t seem to have the five or six really good players that can make or break a class, especially over a period of ten days. However, in the end, we had eighteen or twenty people who played. There were no auditions: that’s not necessarily a thing we would repeat in future, because it could cause problems, but this time it worked. In my opening talk to the students I explained that I wanted to include as many people as possible, and I hoped they could, as it were, vet themselves: that is, get an idea of how good they were; and understand that everyone (including myself) would learn as much—probably more—from listening and participating in the discussion, as from simply playing. Often if you’re playing you’re nervous, you don’t listen properly to what’s going on, you’re preoccupied, and in many ways you can learn more by not playing.

So I left it to them, and they had the sense to do pieces not only that they could play, but that they had something to say about (except for couple of people who were obviously not up to it, but nevertheless put themselves into play hook, line and sinker, and wasted everyone’s time). Although the standard was not exceptional, or even very high, none of it (save the exceptions I mentioned) was bad, and some of it was very good; in fact towards the end, we had a young Spanish chap who played Dodgson’s first Partita wonderfully well, and that was a lovely tonic. We had some terrific contemporary music discussions: of Brouwer pieces, Taranto, Parabola, Petrassi’s Nunc, Richard Rodney Bennett’s Five Impromptus… We had very lively sessions on the understanding of dynamics, and what composers mean by them, and so forth; I think that was very valuable.

So the standard overall turned out to be terrific. We had everyone playing easy ensemble music, Prætorius, at the end, just for the fun of it. Relating the course to the original invitation of Paco’s I feel we were infected with a lot of the spirit of Flamenco, of communal music.

You expressed your view on the course about how little meaning handing out pieces of paper at the end had; but I noticed that you divided the diplomas here into three categories. Would that be because you feel that if you put your name on a piece of paper, it’s got to mean something?

Absolutely, yes, I was quite strong about that. The possibility was raised of not having diplomas at all, but since diplomas were general for the other courses, signed by the Ministry of Culture, it seemed silly to make a fuss about not having them. I made the point to the class that I hoped the diplomas would be accepted in the right spirit: that a diploma was confirmation of participation in the whole two-week event, not a passport for someone to say “I have studied with Mr X”, whomever that that might be.

For that reason we divided them into three categories: those that were purely auditors; those who were participating listener students; and fully fledged students, people who not only played sufficiently well (because some of those who played did not get the full student diploma), but who could discuss, defend and explain their way of playing and participate in the discussion of the piece. That I regarded as the essential ingredient, not just being able to play through the work. I explained quite openly that it was my decision to do that, and it seemed to be accepted very well.

Are you anticipating doing anything like this again next year?

I would certainly like to; we haven’t formally arranged anything yet, but I hope so, yes.

In the case of recordings of works like Britten’s Nocturnal, by Julian Bream, people often attach a lot of significance to the interpretation of the dedicatee; because the artist has obviously worked at least to some extent with the composer, and they themselves are unsure of the composer’s intent. And sometimes you get long-time cooperations, like that between Ralph Vaughan Williams and Sir Adrian Boult, or Stephen Dodgson and yourself. How much weight do you think people should attach to that?

Not too much. I think that like everything else, a lot depends on other factors, such as which composer, which performer, the kind of music, the situation at the time the collaboration was formed… it’s a thing that can be very misunderstood. Obviously, if you have to look for some sort of guidance, then where there has been a collaboration the performance of the dedicatee—as in the case of Julian and the Nocturnal—has to be a main guideline.

But I don’t think everyone trying to play the Nocturnal should copy every dynamic; and I don’t think that Julian, or Benjamin Britten were he alive, would think that either. That can become one of the ways in which many performers, whether they’re students of professionals, pass the buck, they want to abrogate responsibility. How faithfully should you follow a contemporary composer’s markings in the score, his dynamics, right down to the metronome speed? In the end, you come to the necessity of understanding the music, reading it, knowing it, trying to understand what the composer intends. In doing that, you will often find that where one composer is very specific with his or her dynamic markings—ritards, sostenutos, staccatos, vibratos, all those things that contemporary music has a lot of—other composers use comparatively little. With Petrassi, or Richard Rodney Bennett, you have directions on almost every note as to how to play it; whereas Stephen Dodgson leaves a lot to general indications and general descriptive words, like vivace, and so forth. So I don’t think there’s any easy answer except to learn how to read between the lines, or between the notes, and make one’s own judgement on the basis of what is given in the score.

Very, very occasionally, you may find that a specific marking doesn’t mean what it might seem to: for example, rests articulated in terms of seconds, like 3 seconds, or 4 seconds. I don’t think in those cases one should use a stop-watch and count. The intention is nearly always a function of the acoustics of the room, and the feeling of silence after the note has died away; it’s something that can only be judged in the circumstances of the performance, and most composers are aware of this.

But with that exception, I think you should follow the markings as closely as possible.

Linked to this, of course, is the question of non-guitarist composers who produce moderately-to-very unplayable music in the first instance: how far are you justified in modifying their music? For instance, Segovia seems to have come in for a bit of stick recently over his treatment of Ponce’s material.

I’m very glad you mentioned that, because it’s come up before, in some absurd letters I’ve read in correspondence columns. Segovia has had a lot of… I was going to say unfair criticism, but the criticism has been so ill-founded and misplaced, that unfair is the wrong word.

You have a particular situation with Segovia and Ponce, where the relationship was so strong, both as a friendship and as a musical collaboration, that the composer—Ponce—conceived the pieces he wrote even more for Segovia himself than he did for the guitar as an instrument. The understanding of that spirit is so implicit in Segovia’s own playing, and his editions, that I think, really, whether some of the alterations are Ponce’s or Segovia’s is absolutely immaterial. Because the spirit in which those pieces are written lives only through Segovia.

Take a specific case in point, the opening of the theme of the Folias d’Espagne: this is in fact Segovia’s harmonisation, following the harmonies of the first and some of the subsequent variations. Whereas Ponce’s original (if anyone’s got the old 78s of Segovia’s first incomplete recording) was a simple harmonisation of common chords, and slightly out of character with the first and many of the other variations. So it was logical and right, in fact more typical of Ponce’s own writing, to have gone the whole hog and harmonised it as indeed it is in the printed edition.

A second example is the Sonatina Meridional, with the alterations and additions to the last movement, and the repeat of the little fiesta tune at the beginning. The alterations are all Segovia’s. But they’re undeniably, from every point of view, more Ponce than Ponce originally wrote it.

I’m reminded of this—I must tell this little anecdote, I mentioned it in the class and I think it particularly applies to the whole of Segovia’s relationship with Ponce—of when Thomas Beecham was conducting a Haydn symphony. He was criticised at one time by many musicologists for altering the string parts at the end of one of the movements, from ordinary arco bowing to pizzicato. David Cairns, a great music reviewer and writer, pointed out that what Beecham had done was such a quintessentially Haydnesque touch, that Haydn must be kicking himself in his grave for not having thought of it.

But with regard to the relationship between Ponce and Segovia: although we’re now talking about a specific example, are you not contradicting what you said previously? About not attaching significance to the interpretation of the dedicatee?

No, I’m not. Because I said one should not necessarily attach significance, not never.

I think it’s true of a lot of issues, we’re tempted to make rules. I prefer to use rules that allow you to do things: that tell you what you may do, not what you can’t do.

Finally, John, they tell me you don’t like being asked all the time what strings you use.

No.

What kind of strings do you use?

Nylon ones.

Further Information

John’s website includes a discography of the albums on his own (since 2014) label.

For the rest, an excellent discography may be found here.