William Coulter

interviewed in 2002

Classical guitar and folk guitar are interests that seldom meet—few classical guitarists have taken enough interest in the traditional music of the British Isles to arrange and record it.

The recent surge of interest in Celtic music is changing this. David Russell (himself Scottish of course), has recorded a complete album of it, Message of the Sea. The attitude of the English to Celts, too, seems to have improved somewhat since the days when Elizabeth I ordered all Irish harpers and pipers to be hanged on the spot. In particular, the music of Turlough O’Carolan is enjoying a popularity unequalled for hundreds of years, and especially among guitarists.

O’Carolan (1670–1738) was, as many will already know, a blind Irish Harper. The initial revival of interest in him was sparked largely by the recordings of Derek Bell, of the Chieftains (although for my money, easily the best harp album of O’Carolan is O’Carolan’s Dream, by Aryeh Frankfurter—and yes, I'm serious, un-Celtic though his name may sound. See Aryeh’s website, www.lionharp.com for more info).

O’Carolan’s music entered the tradition, and was notated after his death by collectors such as Edward Bunting. But although a few harmonized arrangements exist from that period, their fidelity to O’Carolan’s originals is in serious question, and his tunes survive mostly as single-line melodies. The arranger, then, has carte blanche as far as harmonization goes, and many recorded arrangements now exist. Some are brilliant, but some are pretty clueless, few classical guitarists having the dedication to learn the idiom thoroughly.

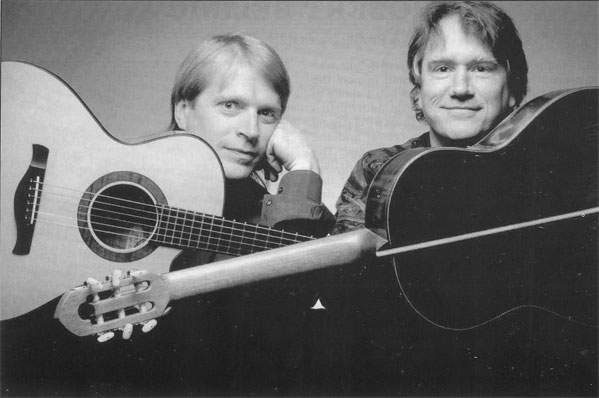

One who has taken the trouble is William Coulter. In fact, his affection for folk music grew to such an extent that he has now “crossed over”, so that traditional music forms the major part of his repertoire. I first met him through Ben Verdery (q.v.), when they were doing concerts to promote their recent duo CD, Songs for Our Ancestors; and after a few minutes conversation with him, I knew he would be the ideal person to interview about the division separating the classical guitarist from the folk musician.

For this issue, he has kindly given us one of his own O’Carolan arrangements1.

William has been recording and performing traditional music since 1981. He has also performed with the bands Isle of Skye, Orison, and the Coulter-Phillips Ensemble. He has recorded three solo albums, as well as three albums of traditional Shaker melodies with ’cellist Barry Phillips. He has appeared on compilations produced on the Narada, Windham Hill and Hearts of Space labels; four of these recordings have appeared on Billboard magazine’s “top ten” lists.

In 1998 he produced Celtic Requiem for Windham Hill, which features vocalist Mary McLaughlin. He has most recently recorded a CD called Songs for Our Ancestors with the classical guitarist Benjamin Verdery.

As well as performing and recording, William works as a producer and recording engineer, and teaches guitar at the University of California, Santa Cruz. During the summer he teaches at a number of music camps, including the National Guitar Summer Workshop, Alasdair Fraser’s Valley of the Moon Scottish Fiddling School and the Puget Sound Guitar Workshop.

Did you train originally as a classical guitarist?

Yes. I did an undergraduate degree at the University of California here in Santa Cruz, and then a Masters at the Conservatory in San Francisco.

Did you have a subsequent career as a classical guitarist?

Not really. Most of the playing I did with the classical guitar was in ensembles—the main one was with a cellist, a flautist and a woodwind player. We did our own arrangements, things like Holst dances, Debussy’s The Girl with the Flaxen Hair, that kind of stuff. And I was playing nylon-string in that group, performing and recording; but I never really had a career as a concert soloist.

So what made you decide to switch to Celtic music?

Well, that’s a good question. The first time I really heard Irish music wasn’t until I was twenty years old:

I grew up pretty much on a diet of classical music, because my dad was a singer in a choral group: every morning, he’d play Bach, when we were having our breakfast. And he was always out doing concerts and he would take me to rehearsals, and they played at Carnegie Hall. So I got a good dose of classical music and choral singing as a kid.

Then I moved to California when I was nineteen years old, and in a little café here I heard a recording of The Bothy Band, which just totally changed my life.

They got a lot of people started.

It was unbelievable. The opening track from that record just touched me in a way that I’d never been touched before…

The Kesh Jig?

The Kesh Jig, of course! And also on that record was Fionnghuala, that beautiful piece of mouth-music. I heard both those things, and I was just stopped dead in my tracks. And my brother lived here at the time, and was playing mandolin. So both of simultaneously got interested in playing Irish music, and discovered that there were some great Irish musicians living here.

So I started picking up the steel-string guitar for accompanying traditional music, although at that time I was still studying classical guitar; so it was kind of a concurrent interest. And I followed those two paths together for a long time—maybe twelve years.

So you were accompanying traditional musicians as well?

Yes, mostly singers and dance musicians—jigs and reels.

Was that purely fingerstyle, or did you use a flatpick as well?

Probably half and half: the flatpick I used (and still use) for the dance music, the fingerstyle for the songs, airs and so on.

What stylistic changes, or other adaptations, did you have to make?

Well, I think the classical training as far as technique goes has been nothing but helpful. But when you play on steel strings, there are different issues.

For instance, the steel strings just wear away your nails—so quickly, far more quickly than nylon ones do. So I ended up getting acrylic nails, which have become quite popular among steel-string players. Tone is not the same, but I can play for hours and they just don’t wear away. That was a technical consideration.

Stylistically, I think my way of accompanying traditional music has a lot of classical guitar in it: arpeggiation, parallel thirds and things, maybe a moving bass-line that comes from hearing a lot of polyphony as a kid.

I know that a lot of classical musicians have been turned on to Irish music by the compositions of Turlough O’Carolan. Do you have O’Carolan pieces in your own repertoire?

Yes I do: I’ve done many of his pieces, and just totally love his music. Sí Bheag, Sí Mhor, of course, everybody plays; that’s been a great piece for me. His music is like half-way, in two worlds: he’s really a traditional musician, but he heard classical music a lot, especially when he was in Dublin. And you know there’s the story of his meeting Geminiani, the great Italian violinist, and their having a competition to write a concerto on the spot; O’Carolan apparently won that…

But all the judges were Irish!

Exactly! And O’Carolan was one of those musicians who managed to move both in the Irish-speaking world and the English-speaking world. He was very comfortable in both, and the love songs are in Irish, and the party drinking songs in English. For that time in Ireland, that was very unusual.

What tunings do you use for this music?

Mostly DADGAD. In my recordings I often use other ones, for instance DGDGBD, and occasionally I’ll play in standard tuning. But mostly these days it’s DADGAD.

And what are the advantages of that?

Many. I think that DADGAD became part of the tradition because of the ability to use the open strings (both the bottom and the top) as drones, and play chords within that, on the middle strings. And I think that actually relates to the Uilleann pipes, mimicking the sound of the drones as an accompaniment, and then being able to move melodies around inside of that.

It works great for strumming, although there certainly are disadvantages: I use a capo quite a bit, and if you move the capo around, it effects the tuning, which is something you have to deal with.

But the other advantage is that the resonance of the instrument can really be beautiful when you’ve got more open strings sounding.

Yes—you can play the same notes on a guitar in DADGAD and one in normal tuning, and they will sound quite different.

Right. It’s like playing in E minor on a standard guitar, the D stuff is just so resonant.

And it can be easier to get campanella fingerings, as well.

Yeah, although what’s harder about it is playing the tunes—if you’re going to play a fiddle or flute tune, it doesn’t fit that well, because of that tone step from G to A.

Who are the musicians who have influenced you?

Well, in a record I did called Celtic Sessions (which was the second of the three Celtic things I’ve done with other people), I got to play with Martin Hayes, who’s a fiddler from County Clare. And the way his tunes build, the way they rise and fall, is just so wonderful. And accompanying him was a great joy because of that.

And there’s another fiddler, from Scotland, Alasdair Fraser. I did a couple of tours with him and learned a great deal about the pacing of traditional dance music. I had a tendency to rush, so I learned a great deal from these guys about steadiness, how to make it sound fast without actually going faster.

There certainly can be a temptation to play loud and fast, especially when you’ve got a crowd that wants that…

And it’s exciting, it is dance music, so much of it.

Another guy who’s been very important to me is Todd Denman, who plays the Uilleann pipes. He gave me some great tunes that I ended up recording. And he taught me a lot about the style of ornamentation in Irish music. Although I don’t really struggle to play that on the guitar, because you can’t—each instrument has its own type of ornamentation, and I try to make the guitar do what it does well, not to make it sound like pipes.

But just understanding the ornamentation, and the way they talk about it, helped me quite a bit.

And finally, I think the most profound influence on me has been listening to singers, like Máire Ní Bhraonáin. And even a singer like Enya, who’s so well known for (what we might call) Celtic muzak, was an enormous influence, because I heard her singing these very simple traditional melodies in a context of beautiful orchestrations.

Half of every album that I've done has been instrumental arrangements of what were originally songs, I love playing song melodies.

They’re the most accessible to the Spanish guitar, certainly, more so than reels and jigs…

Right. I love accompanying reels and jigs, but my solo arrangements tend to be song airs.

And then I’ve really been influenced by this guy Ben Verdery. It’s been a nightmare, but my therapist says that in two or three years I should be OK [Ben was present at the time of the interview—PM].

How do you learn traditional pieces? Do you take them out of collections like O’Neill’s? Or do you play them by ear? Or is it a combination?

It’s a combination. It’s interesting, because Irish music is very well documented in notation. There are so many great collections of printed Irish music; yet (as you might say) in the trenches, traditional Irish musicians might be able to read music, but it’s rare that they actually do—all their learning comes by ear.

And for myself, coming from a classical background, having the availability of the notes has been great: because if someone wants to play a particular tune, I can go find it maybe in O’Neill’s or Breathnach. But the setting and the ornamentation, I always try and get from another player—this is what Todd helped me with so much.

Like, I’d learn the notes of a jig, and we’d play together, and I’d hear the way he’d change and ornament things. And his setting would be so different from the printed music…

Have you read a book by Ciaran Carson called Last Night’s Fun? It’s a great book about traditional Irish music. He spends a lot of time talking about the process of how music passes amongst musicians, and how you can get the notes off the page, but you can’t actually get the music off the page. To get the music, you have to sit with a player.

I’ve probably learned more tunes by being with musicians—I might consult a printed page, but it tends to be more by ear.

How did your collaboration with Ben come about?

Well, we met about fifteen years ago, when he was in California playing some concerts, and I was beginning my classical guitar studies.

I went to hear him, and we met, and we found we had some things in common. And then over the years we ran into each other at festivals and workshops, and I took some lessons from him here and there.

And then, on the first Celtic record I did for Gourd music, I invited Ben to play an O’Carolan piece (O’Carolan’s Farewell to Music), with a nylon-string and steel-string; which really was the genesis of the idea of playing together, because we love the way it sounded. It’s such a beautiful melody, and very classical, and fit perfectly with Ben’s style of playing.

And then, on my most recent Celtic album (The Crooked Road), we collaborated on two pieces: Women of Ireland (the Seán O’Riada piece); and the other was yet another O’Carolan tune, Eleanor Plunkett.

And it’s been the result of a friendship, rather than two guys sitting down and saying What can we do?

Do you ever get any criticism?

Sometimes—you’d be surprised. But, in a way, I kind of like that: I’d rather have someone either love something or think it’s ridiculous, than have them say “Oh, that’s just the same old stuff”.

Does the criticism come from the classical camp or the traditional camp?

Well, there are always people who want you to play things in what they think is the right way. And the way I play traditional Irish music is not the right way to a lot of people. First of all, I’m playing it on the guitar, which is not a traditional instrument.

So you can take these things in a positive or negative way: it’s good that these people love and care about the music, and they want it to be the right way. On the other hand, it’s not so much fun getting the e-mails about polluting Irish music…

But then, you can take Martin Hayes, who is one of the greatest traditional musicians, and he loves what I play, and we had a great time recording. There’s always so many different opinions.

So purists might not like our new CD; but if things don’t evolve and change, then it’s not really traditional.

Further Information (including a discography)

Notes

1Those who wish to pursue O’Carolan’s music further may be interested in the following books:

The Complete Works of O’Carolan (Ossian Publications) for the melodies.

Anthology of O’Carolan Music, ed. Grossman & Renbourn (Mel Bay) for guitar arrangments.