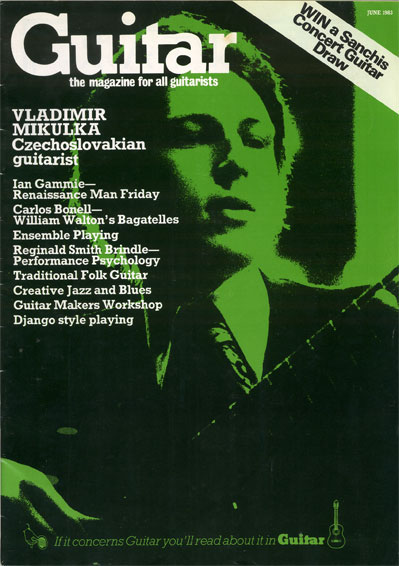

Vladimír Mikulka

interviewed in 1983

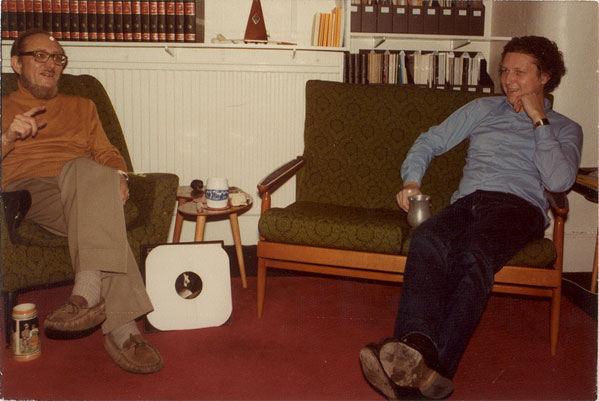

Since winning the ORTF competition in 1970, Vladimír Mikulka has established a reputation as one of the very best young guitarists, pre-eminent in playing the music of his native Czechoslovakia. A major landmark in the presentation of the modern repertoire was his excellent Wigmore Hall concert last year, consisting entirely of first performances of works by his compatriot Štěpán Rak and the Russian Nikita Koshkin. Lance Bosman and I seized the opportunity of talking to him about his relationship with them and his view of modern music in general. The discussion turned out to be so interesting that it lasted past the formal end of the interview through most of the night, seeing the demolition of large quantities of Indian food (for which Vladimír has a passion), and many pints of beer.

First of all, though, I asked him what he had been doing since we last spoke to him in 1978.

At that time I was studying lute here in London, at the Early Music Centre; it was organised by the Czech Ministry of Culture and the British Council. Then I went back to Czechoslovakia and continued studying repertoire, teaching and giving concerts, and that’s what I’m still doing. I’ve recorded the Giuliani Concerto in A Major and the Haydn D Major for Supraphon, and a disc of 20th-century music. And also another one, one side each of Sor and Giuliani.

Last time we saw you, you said there were only about three performing guitarists in Czechoslovakia, and there wasn’t really a very big audience. Has that changed, is the situation improving?

I think so, it’s like mushrooms after a good rain, because guitarists are really becoming numerous now. In confirmation of that, you can see that in the finals of the Paris competition there are three Czech guitarists, and another one in the reserve. So there are more guitarists and more public, because the two go together. The guitar is better known and has more respect, even though there is only three or four years difference.

Would it be possible now, then, to study guitar as a first instrument there?

Prague Conservatory was one of the first in Europe where the classical guitar was established straight away as a basic instrument like the piano and violin. If you wanted to study guitar as a main instrument, you could do that; the only obligation was to study piano as well. But now I think they are considering establishing guitar as a main instrument in the Academy, which is one step further.

You’ve been paying a lot of music by Štěpán Rak in your concerts. How did you get in contact with him?

I already knew him from my studies in the Conservatory, and soon we became very good friends, and we met regularly all the time—although there was an interruption of five years when he was teaching in Finland. But still we kept in contact, and I had news and new pieces from him.

I remember you said it’s hard for him to write things down, he tends to keep his pieces in his head?

Actually, he has written down many pieces; but there are always some new compositions which are waiting to be put on paper. There is some music published by Rak, but not Farewell Finlandia, because that was only written recently. But there is a Toccata, a Suite and some other things, published by Supraphon.

Do you ever commission pieces?

Not very often, because if you commission a piece you have to play it, and you don’t know what you’re getting. And besides, you don’t want to ask a composer, Do it lyrical, or Do it very dramatic, etc. I would rather say, Please compose anything you like. Rak is such a good friend of mine anyway, I don’t have to ask him to compose something for me. I think I was the first guitarist actually to play him, while still studying at the Conservatory.

In The Sun, the opening is very evocative of Debussy, although the later movements are not particularly impressionistic. Does Rak have a particular affinity for that music?

Not at all, I think you could call him a New Romantic. He’s certainly not the kind of person who would compose very much in any one style. As you can see from his pieces, they are inspired by many different things and themes and periods: for example, the Air, Variations and Dance is based on his own theme, but in the style of Renaissance music. It’s called Renaissance Temptation because he is tempted, as a 20th-century composer, to make changes in the piece, rhythm and so on, that would show it is not an original work of the period. Then you can see The Sun, and Hommage à Tárrega, which are in a very different spirit.

The special effects in some of the pieces: is the written music enough, or do you have to talk to the composer to see what he intended?

In a few cases we had a discussion, but mostly they are in such a form that a variation of detail is not of great importance.

How did you come across [Nikita Koshkin’s] The Prince’s Toys? Have you met the composer?

Koshkin is a friend of mine as well, he lives in Moscow. He composed the suite when he was nineteen, and I met him when he was about twenty-three. It was in a much simpler shape, and I asked him to reorganise it. But he made it much more difficult and more interesting musically, and he composed new movements. He especially enlarged the last part, which is the Theme and Variations, the Puppet Dance, which is ten minutes by itself; the whole thing takes about twenty-five.

Did you suggest any of those effects to him? Is he a guitarist?

He is a guitarist. It was so well thought out that we only needed to discuss a few details. The piece is based on a fairy tale, although I don’t know the exact one he was thinking of. It is descriptive music, but at the same time it can stand by itself, and you don’t need to know the story to understand the piece and catch the spirit.

What is the response to contemporary music in Czechoslovakia? Do you see the guitar progressing in that direction?

Very much, because there are lots of composers, you could make a considerable list of those who have written for the classical guitar in the last ten years. There are festivals of contemporary music, for example there is a two-or-three-week one each year in Prague presenting new works by Czech composers. And there is a union of composers, which is very active.

Can you get records of Western guitarists such as Julian Bream?

Not so easily. You can buy records which were produced in co-operation with Supraphon or other Czech companies: for example, [Konrad] Ragossnig recorded Spanish and South American Music in Prague, and [Siegfried] Behrend made one disc also. But basically you don’t get many guitar records, you can’t compare it with the choice here. Concerts are better: [Alirio] Díaz was in Prague, Bream twice during the Spring Festival, [Narciso] Yepes has been several times… many guitarists from different countries have visited us.

You did all your study in Czechoslovakia. Did you find, when you went to the western world, and met other guitarists, that your style or technique was different?

I think that it doesn’t matter where you are, it’s different for each person, and I just forget about putting it in the box of this or that school. The guitar is a very personal instrument, and you can produce a very personal approach to it. The important thing is what sounds are coming out, and if perhaps the sounds are not very nice then this is the point when I start to think that something may be wrong.

So I think that healthy musicianship should be the main point leading a guitarist to produce good sounds. Being well informed is a good thing, but at the same time if you have enough time and enough intuition, you don’t need it so much. Sometimes I think that it’s not very good to be informed at all.

With classical music, of course, you have to accept certain forms and habits which already exist. But to take Jazz, for example, Wes Montgomery was self-taught and had a very peculiar style; but would you say he was not producing good sounds? It was very beautiful music. I was once told of a very nice comment by an American critic, which expresses what I want to say: he said that Wes Montgomery could even play impossible things, because no one had told him that they weren’t possible. That’s what I mean, because if you are schooled and trained you have to conform to some kind of standard, whereas a musician on the highest level might achieve much more.

On the other hand, for every genius there may be a thousand others who would get into bad habits if not properly taught, and their technique would be limited.

Yes, there is that also. It comes down to this, that nobody knows the best way to school people to make the best guitarists, it’s just impossible.

Do you think it important to be able to analyse the academic structure of modern music to be able to interpret it convincingly?

Of course, it’s part of the whole process of how to study a piece of music. I think it begins with, do you like the piece or not, do you feel something for it? You should not play pieces you don’t like. You take a piece and you study it, and because you like it, you want to know everything about it. You should analyse, you should know something about the background. For example, Elogio de la Danza, by [Leo] Brouwer: you should know something about Cuban folk music, in which rhythm is so important. And if you feel it in yourself, you get an understanding of the culture and the country, although you may never have been there.

An important thing is to put conviction into any piece that you play. You might play a piece which is supposed to be fast at a slower tempo, but then you would have to use other equipment—for example, different accents, or more pronounced accents, more vibrato, more colours, to fill the space. If you use the right equipment, you can make the piece seem as fast as another player who is playing it very fast but perhaps is not using many accents.

Conviction is the most important thing in performance.

Discography

Vinyl

| Year | ID | Title | Discogs | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1977 | Supraphon – 1 11 1585 | Compositions By J.S. Bach | Buy LP | |

| 1977 | Panton 11 0608 | Concertos for Guitar and Orchestra | Buy LP | Castelnuovo-Tedesco Concerto & Rodrigo Fantasía |

| 1982 | Supraphon 1111 3028 | Sor and Giuliani | Buy LP | |

| 1982 | Supraphon 1110 2700 | Haydn & Giuliani | Buy LP | |

| 1990 | Supraphon 10 2825-1111 | Kytarový Recitál | Buy LP | |

| 1991 | Supraphon 11 1418-1131 | European Guitar Premières | Buy LP | |

| 1991 | Supraphon 11 1443-1111 | Guitar Recital | Buy LP | |

| ? | Curcio TMC-91 | Johann Sebastian Bach: Preludi E Fughe | Buy LP | Includes 2 tracks by Vladimír. |

CD

| Year | ID | Title | Amazon | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1986 | BIS CD-240 | The Prince’s Toys | Buy CD | |

| 1987 | BIS CD-340 | Iberoamerican Guitar Music | Buy CD | |

| 1995 | GHA 126.032 | Classics from Bohemia | Buy CD | |

| 2003 | GHA 126.003 | Voces de Profundis | Buy CD | Music of Štěpán Rak |

| 2006 | Lotos LT-0042-2 131 | Virtuoso Guitar Pieces | Buy CD | |

| 1986 | Denon 28CO-1196 | Your Guitar Favourites | Buy CD | Includes 3 tracks by Vladimír. |

| 1991 | Denon DC-8100 | Masterpieces for Guitar | Buy CD | Includes 2 tracks by Vladimír. |

| 2010 | Integral Classic ? | Elogio de la Guitarra | Buy CD | Includes 2 tracks by Vladimír. |

| 2015 | Denon OX-7164-ND | Guitar Recital | Buy CD |