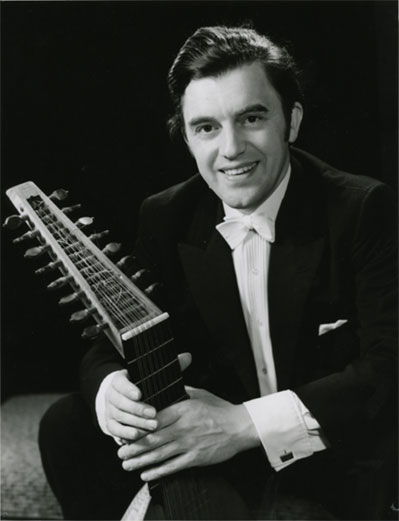

Robert Spencer (of The Julian Bream Consort)

interviewed in 1988

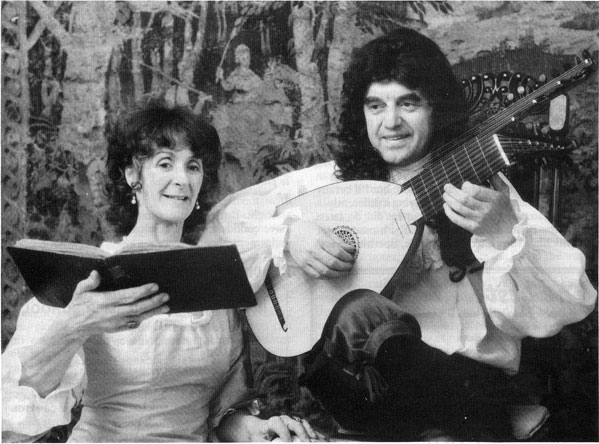

Robert Spencer, although perhaps best known to the public as a member of the Julian Bream Consort, is in fact one of the most respected scholars in the whole of the Early Music field: one of the small, distinguished band that opened the whole area up for the rest of us in the late ’50s and ’60s. First-rate both as a lutenist and singer, he played for the Royal Shakespeare Company from 1961, and at the same time was a founder member of the Consort. He has worked and recorded with Dame Janet Baker, Alfred Deller, James Bowman and the Kings Singers, and is Professor at the Royal Academy of Music. He also appears frequently in collaboration with his wife, Jill Nott-Bower, with whom he has given over 2,000 duo recitals (that’s a lot of duo recitals!).

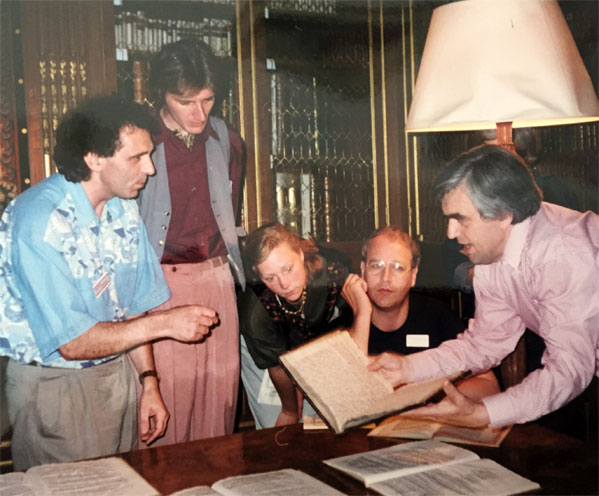

We had met before, both being members of the Lute Society; but this conversation (conducted during a U.S. tour with the Consort) was the longest I had yet had with him. Far from being the dry academic the subject might conjure in the imagination of the uninformed, he is one Early Music’s most charming and articulate representatives, with the happy gift possessed by only a few (David Attenborough comes to mind) of catching people up in his quiet enthusiasm. His interests range over a huge variety of topics, as manifested (after the interview) over a pizza—and indeed, I wished I’d still been recording some of it. However, his real interest is lute song.

…Specifically, English lute song: because I think so far we still haven’t rediscovered the right style for singing them. I teach at the Academy in London, and I have a Lute Song class—I think, with the students there, we’re hammering out a new approach. But my own work is mostly giving concerts, and wherever I can, it’s solo programmes with songs. However, as you know, songs are not easy to sell: most people are not very interested, promoters are not very interested in song concerts—I think for the reason that more is demanded of the performer than for straight music programmes.

In a way, the violinist, or the harpsichordist, or whatever, can hide behind the instrument—it’s pure sound that comes out. A singer must face the public with his whole personality, and therefore you’ve got to be that much better to be interesting to an audience, and not embarrass them. So many singers embarrass the public, that’s why they don’t want to go—they make faces, and they make nasty sound. Somehow you’ve got to draw people to you, and not push them away.

Because I think the Elizabethans listened to songs in a different way from the way we do today—this is pure guesswork, obviously, I don’t know. But just by looking at the material, and looking at what people at the time said about songs and singing, I think you can begin to draw conclusions. And the biggest conclusion I draw is that the English lute songs (there are only 500 of them, written between 1597 and 1622, or whatever it is)—were not really written for professional singers. They were written for people who were interested in ideas expressed by poems: words, and the ideas behind them.

And I think that the Elizabethans listened to the songs primarily as an expression of words. Second to that comes the vocal line, the music of the songs; and third comes the actual singer.

Now today, merely by the way song has gone over the last 400 years, people are most aware—I think—of the voice first, secondly the music, and third the lyrics: in other words, the whole thing’s tipped over. But if you approach the songs from the words, while you’re singing, you’re totally involved in what the words are saying—I mean, since I did the record you mentioned1—that’s 25 years ago, and I may have done things instinctively then. But let me tell you, in 25 years I’ve done an awful lot of thinking, and it’s become more structured. And it was really the discovery that the composers, starting with Dowland, got interested in the idea of colouring words, displaying their meaning by musical means.

For instance, if you put a discordant harmony with the beginning of Sorrow, Stay—you sing the third above the tonic, beautiful. And then, slap in the middle of that word sorrow, you get a discordant harmony—you’re singing a B flat, and you’re playing D major, first inversion. It’s pretty horrific. And I think that Dowland wants to colour the word half way through it, to make you realise what sorrow means in musical terms.

If you sing with the mind concentrating totally on expressing the words… almost onomatopoeically, you make the sound that is internationally the sound of the word—no matter what language you speak, you can understand it. And if you sing in that style, I think you really do draw the listener into the poem, very much so.

So I believe in a rather passionate style. I think a lot of people think Early Music singing means sounding un passionate, uninvolved, rather like a choirboy, and not disturbing the listeners’ emotions at all—it’s as though you’re looking in at the music through a window, and you’re not actually in the room with it, you don’t get involved with it.

I think the listeners must be involved with the music. It’s the performer’s job to stir them up, to pull them into the poem, and make them feel everything. And I’ve looked up what people said about acting at the time—in Hamlet, Shakespeare says a lot about how actors should act. And I can’t believe acting style was different from singing style (that’s a guess on my part, it could have been different).

And then, in the music, I found various pointers: like these curious rests in the middle of words. For example in Come Again, you get (sings) “die… with thee again”. And between “die” and “with thee again”, there’s actually a silence—which is extraordinary, when you think of it. I mean, the sense is “die with thee again”, right through the middle. And I’ve come to the conclusion that those holes are not silence, they’re an intake of air, a sort of sigh; which actually, when you apply it to all those places in the music suddenly makes it sound very passionate.

So you’re saying that this was part of the performance conventions of the time, that musicians were expected to know, in the same way that musicians of Bach’s time were expected to know those performing conventions?

Yes. The Early Music movement has concentrated on this idea of “How did they do it”, as far as one can ever find that out. I think it’s essential to know that, as the first thing. And then—not necessarily to do it, because perhaps we’re using music in a different way today. For example, we make up 1½-hour programmes, carefully structured, with an intermission in the middle. Whereas then, I think, that would be unheard of, it’s a modern concept.

So if we’re going to use their music in a modern situation, we might have to vary some aspects of performance practice of the time. But the basis of how to sing the songs—I’m interested to know how they did it, and I think we should do it the same way.

I think that since then, the rise of the professional singer encouraged composers to write for the voice almost like an instrument. Now, that’s not true of Elizabethan times, because the songs are set, normally, one note per syllable; and this syllabic setting draws attention to the words, not the voice.

Whereas, think of Handel, where you might get 28 notes to one syllable! That is drawing attention to the voice, and not the words.

O.K. But that’s Elizabethan music. It’s not equally true of, for instance, Italian music of the period, is it?

No right. I think the Italians were using professional singers at their courts.

Whereas the Elizabethans’ orientation was towards amateurs?

It was, we know. For example, Danyel’s book is dedicated to his pupil, Anne Green, and says, “These songs were first composed for you in your house”. Anne Green was no professional. It was just the English convention at the time to teach, particularly, the girls, to make them more marriageable—so they could have a social grace they could offer as well as the dowry.

So they were amateurs; but interested in expression of words, and refinement of expression. And that’s a style I’m working towards all the time.

I haven’t done solo song recitals until very recently—I mean, to maintain a whole evening solo is asking a lot of your audience, as well as yourself.

Do you sing songs from the rest of the continent?

Not… really. I just feel I should do something that I’m really getting my teeth into now. And I’m so interested in language as a means of communication, that I tend to be a bit shy of using foreign language: you know that you can’t be doing it as well as your own language. I mean, I sing French songs, and Italian, and German, but I try not to use them in proper programmes.

You probably know Barry Mason. His group made a record2 where they tried to reproduce Elizabethan pronunciation…

Yes. Now, you see, I don’t go for that at all [laughs]. Mainly, I think, because language is communication. If you hide it, however much that’s the sound the Elizabethans heard… that, to me, doesn’t seem to be interesting. What interested the Elizabethans was to understand what the words meant, not the sound. Therefore, if you make it into a foreign language, you’re drawing attention to the singer and the music. And I think we should draw their attention to the words, and what the words mean.

I think it was of interest to do it, though, just to see what it sounded like.

I agree, absolutely right, I’m all for experimenting. But for me, it’s defeating the main purpose of the songs, which is to communicate ideas. Therefore I wouldn’t do it.

Also, you’ll notice, on that record, they tend to introduce a little instrumental interlude between verses, which again is pushing songs back into abstract music. I mean, however interesting that is in a programme, you’re encouraging people to listen to the songs as tunes, and not as a series of ideas expressed by words.

For example, a lot of people think of Campion: little four-square tunes, and there are twelve verses, all to the same boring tune. So when you get to verse three you should start introducing ornamentation, both in the voice and in the lute. And again, I think that’s totally wrong, because by verse three, you’ve got a different set of words from verse one; and you should be encouraging your listeners to hook on to the story, and not deflecting their interest to how clever the voice is, or the ornamentation. And again, it’s an approach to song which has come about just through developments in the 19th century—thinking, “big voices singing operatic arias showing off”. These early songs I don’t think are show-off pieces for the voice, at all. Quite the wrong way round.

I’m glad to hear that all this interests guitarists because I’m keen… when I do summer schools and that type of thing, I actually invite guitarists to come. A lot of people think “Oh, lute songs, you’ve got to do them on the Lute”—I don’t agree with that at all. You can do them on the guitar perfectly well—in fact, I’d even go further than most people and say, “Why not do them with piano?” I think you’ve just got to learn to play the piano, and the guitar, in a style that’s relevant to the songs. That’s the only difference.

So I agree with you, this should be an interesting subject for guitarist, because they often get asked to accompany lute songs; and therefore, to consider what the style should be is highly relevant to them.

In fact, I made my class at the academy probably the only Early Music teaching place in London where guitarists are really welcome. And I’ve even got a lute and a theorbo now, that the Academy owns, for the guitarists to borrow and experiment on, to see how they get on with it, and see if they want to double instruments.

Of course, at the beginning of the Early Music movement, I think lutenists said “Go away!” to guitarists. That was a terrible mistake. In their anxiety to be so authentic, they thought modern guitar had no place. It was a great shame that happened. But that’s all changing now, I think people are much more open-minded.

I tried it myself once: I rented a lute from the Society, and had a go. Of course, it’s quite traumatic if you’re not used to it: the string spacings are different, and you just can’t hit a lute like you can a guitar—the string tension is all wrong, and you just produce nasty noises. Do you play… I mean, Julian Bream quite unashamedly plays a lute that’s designed so it won’t be too much of a change when he switches…

Well, my personal history is that I started playing the lute in about ’55, and I learnt flesh technique, little finger down. And then I heard Julian play (it was probably ’56 or ’57) and I thought that he actually makes it sound more like music than any of the lutenists of the time—that was any of them. And the natural reaction was, O.K., I’ll play the way he does. So I changed to what we might call standard guitar technique, and played like that for a bit. And then I did find the attacking sound of nails was a bit fierce for the music. And I’m still using nails now, and I tend to keep them reasonably short, and I try and get a friendly sound [laughs] out of the lute.

So I slowly reduced the tension of the strings. And I would guess the string tension I have now is probably half of what Julian’s is. It really is very small, but it’s still not like an authentic lute of the time. I’ve tried that, but so often we get put into biggish halls, where frankly, if you’re using gut strings and a lightly strung lute, it isn’t going to work. I’ve been in the Queen Elizabeth Hall, and heard, for example, the Kuijkens play on viols that were so lightly strung it just didn’t come across—it’s not practicable. And, honestly, however appropriate the technique was for the music, it was not appropriate for the hall, which holds about eleven hundred.

That’s why I say, we’ve got to know what they did, but I don’t think we should always do it, because we’re often using music in a different way.

Now this, you see (plays several chords) is not too fierce a sound, it’s not what you’d call a guitar sound really—but it has an edge to it because I’m using the nail, and I know it will carry, so the back row can hear it. But the string tension is way below that of a guitar.

Anthony Rooley was saying that he finds he hasn’t the strength to hold down a guitar any more, after all these years of playing lute.

Nylon strings, too, right?

Oh, yes! Gut, I think, is a big mistake. I love the sound of it. That’s where you have this terrible dilemma: for making gramophone records, I think it’s splendid, because the mike’s only two metres from you. And therefore an intimate type of technique—no nails, gut—works wonderfully. And if you’re in a small room with some people. But if you’re trying to make a living at it, you’re not going to get jobs that only have twenty people in the audience.

I’ll tell you another point on that, which is also interesting. Why is it that, in the 17th century, both lutenists and theorbo players played with nails?—we know that, they said so, people like Piccinini… Weiss talks about it. The only solution I can come to is that they wanted to balance musically with the singers and instruments they were accompanying; and the only way that they could think of doing it was to get a little more attack by using nails.

Now, they had a practical musical response to the musical requirements, and they used nails. And I feel my reaction today is the same thing.

Then you get these agonised debates about thumb under (where the thumb plucks towards the palm, Ed.) and thumb over as well.

Well, there’s a point. You see, music before about 1590 should be thumb under. If you’re going to do a programme that features music before 1590, and after, and Baroque lute, it’s very difficult to have three different techniques, it really is. I mean, I’ve known people who try and do it. But again, the very fact, why did they change the hand position? They must have found thumb under was unsatisfactory for some reason. Therefore, I use thumb out for all music.

There’s the same problem for other instruments. A keyboard player now, if he’s going to play Byrd, Couperin, Bach, Beethoven, Schoenberg, in one programme… what’s he going to do? Have a row of different instruments that you wheel on after each piece? Or do you say, I’ll play all this on the piano. I think one’s got to be practical: there are limits to how authentic you can be.

There’s something Tony Rooley said, too, about gut strings not standing up to the touring schedule of being Monday in New York and Tuesday In San Francisco, they just go haywire.

Well, some people still do it. And there are even people who make a success of it. But I think it makes for a very hard life. For instance, in last night’s hall, the Herbst: it was very dry in there. And with gut strings, you’d have had a hell of a business tuning, because of the change in humidity along from the damp outside. Whereas—you probably noticed—I didn’t tune once. Because I got there in plenty of time (we got there at 4 o’clock in the afternoon), and when we went to the hotel I left the lute backstage, so it was in the same atmosphere. And therefore I coped with the evening without having to bore the audience tuning.

The Consort performs a lot less than people would like. Now, obviously, Julian Bream has his solo career. But is there more than that, e.g. the difficulty of getting all the people in the same place at the same time?

Well, I don’t know. I suppose the initiative comes from Julian, as to what he wants to do (of course, you’re planning probably two years ahead, to get everyone to book in, which is difficult to do).

As regards gut strings: a feeling I often get, playing through tablature, is that composers of that time did not like the upper reaches of the fingerboard—they have to use it on the 1st string to get a high note, but when they’re playing scale-wise, they will never go across the strings: if they’re up in the seventh position, they scurry down to the bottom as soon as they possibly can. And I wondered if that was because of the unreliability of the tuning?

I suspect that it could well be so, yes. Because they do tend to be… I mean, particularly when you’ve got pairs of strings, and as you know, then, very often the top string was in pairs. And to get two firsts in tune… they may be in tune on fret one, but as soon as you get to about fret five, they wouldn’t be.

If you look at the music of Robinson, in some of those divisions, he scurries up and down the 1st string, with two or three shifts on the way, which is very difficult to do, I think. And he actually gives you left-hand fingerings, which are most extraordinary to our modern way of looking at it, and the most horrific shifts which are quite dangerous [laughs]. When I play the pieces, I change the fingering, and use the 2nd string.

In fact, tomorrow we’re doing the Johnson Flatt Pavan, and that, again, runs up and down the 1st string. And I’ve re-fingered it using the 2nd string; just because I think I can play it more musically. It’s a big point to debate with oneself.

Was the 1st course usually single? Or double?

Dowland, in the Varietie of Lute Lessons, talks about “setting up your trebles” (plural), meaning it’s a double-strung 1st course—Robinson says the same. And when you see the old lutes, you’ll usually find that it’s twelve pegs, not eleven, for a double-strung 6-course lute. They seemed to reckon on its being double-strung.

I use a 9-course instrument—Dowland used nine from 1600 to 1626 when he died, he never went to ten. And I find that’s ideal. You see, I use movable frets, because we’re at A = 440 Hz for this tour, but for myself I prefer to be at 415: I think the instrument sounds better, and it suits my voice better. When I tune down, I actually have to change the frets, or it’s not in tune. And you can see that that’s why they had movable frets, because (as you know) there was no standard pitch then.

It’s so lovely reading those old tutors—for instance, that great bit about where to store the lute3. Why does it strike us as funny now? It’s not just the weird spelling, people seemed to put sentences together in a different way.

Yes, It’s the way of thought. Although Mace, who tells that story, does have a very idiosyncratic way of writing, it’s not normal style.

Is it possible it can be intended to amuse, to entertain? Because I think that almost anybody who’s writing has that in the back of his mind.

I doubt it with Mace, he’s deadly serious. He was worried that interest in the lute was dying out, and determined to do this book.

Now: editions of lute music for guitarists. Opinion has changed radically in the past thirty years. Once, you left the 3rd string up to G, and if there was an unobtainable F# in a chord, you just forgot about it, or went through all those contorted fingerings. And even now, a lot of editions aren’t what they should be. So, assuming you want to get a look at the original tablature, where can you get hold of it?

Well, in the Lute Society, we’re going to print the lute music of Philip Rosseter, which is very interesting, good music, and there are only eight or nine pieces. (Fortunately, there’s only one text left, so we don’t have a problem of editions, of which one do we choose.)

We’re going to print each piece in three ways: a facsimile of the original (which may sound pedantic and fussy, but I think the player should be encouraged to see what was there); then we’ve done a keyboard transcription, which is not so much use to guitarists, but it’s got everything we think the music is trying to say as music, voice-leading and so on; then we’re going to do a third text, corrected tablature—so you can play it straight off, and not worry about trying to read somebody’s writing of 400 years ago, and of course also iron out all the mistakes

And I would try and encourage guitarists to read tablature—because it’s not difficult—so that they read the literature easily, in other words just tune the 3rd string down. Although that makes all the music rather dark, because you’re relatively low in pitch: that’s the only disadvantage I can see.

You just stick a capo on the 3rd fret.

Yes! Fine! And, as you know, there are various guitar-makers like Bolin, in Sweden, who make these multi-string guitars…

I love the sound of those little things. It’s not really a guitar or a lute, but Göran Söllscher…

He’s brilliant. But as far as Bach’s concerned, people have stopped looking at just the Lute Suites, and they say, Well, some of those are not really playable on the lute anyway, so why not just look at Bach and be done with it? Bach was already arranging violin suites and so on for the lute, as we know, so a lot of people have been transcribing the Violin Sonatas now for lute solo, and making a very good job of it—I mean, Nigel North and Gusta Goldschmidt. Very good editions, too

But coming back to the Bolin guitars that Söllscher plays: to be honest, I think they have a problem, and that is that they are very heavy, they have a lot of wood in them. Now, that means that the notes are very long: you play a bass note, and two seconds later, it’s still the same intensity, it hasn’t dropped off—which is quite unlike the lute. And it means you have a problem then of the bass being too long, you’ve got to stop the last note as well as play the next one, which creates great technical problems. And Göran is extremely skilful at that, he does it very well. But for most of us, it would be a full-time job stopping one sound, let alone starting the next one.

Now, I wish someone would experiment with the same type of instrument—say an 8-string guitar—but make the whole structure much lighter.

The other way of doing it is through strings—we have covered strings now, and that elongates the sound. In Dowland’s time, even the bass strings were uncovered gut, so it went sort of plop, and the sound stopped fairly shortly. And some people are experimenting, in France for example (a chap called Charles Besnainou) making spiral plastic strings: they’re like springs. And you can pull ’em a foot out of line, let go, and it’s still the same note it was before. It’s quite wonderful. And he’s been making those for lute, so that you have bass strings that give you a good bass sound (which is why they had the metal covering, to give the bass quality), but the sound doesn’t go on for too long, the vibration sort of kills itself after a short time.

And I think that was a big stride forward, and whether it can be used on guitar, I don’t know. I wish some experiments could be made along those lines. They will be, I think: because, as you know, we’ve got lots of people making modern guitars now that are copies of 19th-century guitars—Gary Southwell, in Nottingham, for example. He’s making copies, and a lot of players who are interested in 19th-century repertory are buying them. They’re lighter than the modern guitar, therefore the sound is less long, and it’s easier to play in that way. It may not have the projection of a modern guitar, but very often one doesn’t need quite as much projection as some of the modern instruments have been producing.

People are making records with them, too.

Exactly. You don’t need that projection of sound for a record. Nigel North’s done a lot, and Lief Christensen, who’s just died so tragically—he’s done wonderful work in that field of music.

I’ve been interested in that, as you know: a lot of the editions that have come out, like Regondi, the Mertz, the Coste, the Giuliani and the Sor have been partly done from copies of the originals of the originals that I’ve got, so I've always been interested in 19th-century guitar music.

That’s right, yes. Because that’s what we decided the guitarists wanted at that time. It’s a problem to know what to do. We did those duets in that version only to begin with, without them being available for lute at all. And after that, we’ve now done an edition of them—in fact, a second edition—in tablature5. So there you are—guitarists who want to tune the 3rd string down, just get hold of the tablature version, because it’s mostly for a 6-course instrument. And when you’ve got a 7th course, it’s dead easy to re-octave that. A lot of people make a mistake on that point. For example, if on the guitar you were playing a B on the 5th string, and then on the lute there was an octave below, people normally play it again on the 5th string; and I think that’s a mistake. What you want to do—the repeating of the note is for harmonic strengthening, it’s not to repeat the same note melodically, it doesn’t matter. So what I play is the B on the 3rd string, if you’re fingering it properly—an octave higher, two octaves higher than the original. Because all you want to do is get a difference. And you might even get a few more notes, you might strike the F# on the way up. Whatever seems stylistically right for the guitar, is what matters, rather than slavishly following what was written for the lute. It’s seeing what the music is: what does it want to do musically, how do I do that on my instrument, be it piano, guitar or whatever.

In other words, your guitarist has got to think: you don’t just play what’s on the page, you think, What is its function? How can I make it sound the same function? And normally, it’s only what I call rhythmic in-fill, those low notes that you get on the lute. Melodically it’s not interesting: it’s just supporting the harmony, and you get a klonk in the middle of the bar. And it’s just a matter of getting some sort of klonk on the guitar that keeps the movement going, and working out what’s not appropriate. I think that’s a very important point. I would encourage guitarists to read tablature, there’s nothing difficult in that; and they can open up a completely new repertoire—particularly now there’s so much available in facsimile. And that in the end is what I think is quite interesting: finding your own repertoire, and not just playing Segovia’s pieces, in the way he’s played them. Find your own pieces. And now it’s all available; thirty years ago, how many books of lute tablature were available?

Nil. Except maybe for the Varietie, and the corresponding piano edition, with the bad voice-leading. I’ve been looking in particular for Adrienssen’s stuff, but I can’t find it anywhere. The book of 1584… I can’t remember if that’s the only one.

No, there’s another book of his, 1590-something. But it’s available—it’s been reprinted in facsimile, the whole book. One of the books is printed by Minkoff, of Geneva, and one by a name I don’t quite remember6, but it’s printed in Holland, and that’s paperback. The Minkoff one is hardback. They’re rather expensive because there are only something like six fantasies each book, and all the rest are arrangements of madrigals.

There’s still so much stuff that no one sings or plays, though.

No. There’s one point I should like to make for guitarists, because eventually I think this will be important. Guitarists should be encouraged to look at the tablature for themselves—say a well-known piece like The King of Denmark’s Galliard. Everyone at the moment plays the Varietie text. Because they say, the Varietie was printed in 1610, and that’s the text he gave his son; but I’ll bet my bottom dollar that in 1612, he was playing it differently—and, for example, you can see what he did do later, because the Board Lute Book (which is a manuscript book which we’ve printed in facsimile, Boethius Press) contains a version that was written out in the 1620s, when Dowland was teaching this girl, Margaret Board, to play the lute. And you’ll find three new sets of divisions at the end of the piece that are not in the Varietie.

Now, I think that any guitarist should have a look at that, and if he’s learnt to play from tablature, he can just read through it (borrow it from the library, you haven’t even got to buy the book), and see which of those divisions he likes. And then, the audience that come to hear The King of Denmark’s Galliard will think “Wow! Something new in this performance!”. And that’s what it should be like, it should be more lively, musically.

And I don’t see why each guitarist shouldn’t be his own editor, choose what he likes—that’s what happened in Elizabethan times. After all, players at that time would have known the three main strains of that piece, and played their own divisions—not what Dowland played!

Absolutely. Well, with the Boethius Press, we’ve now printed facsimiles of bout 15 English lute manuscripts. So, for example, going back to the King of Denmark: three of those books will have that piece in. And you could try through the variations in those, and you as a guitarist musician get to know the basic core of the piece.

That’s a bad example, actually, because it’s in D, which is B to a guitarist [tuned 3 semitones lower]—so you can’t play it as it stands, because without the 7th string it just… you have to play it at actual pitch, which screws all the fingering up

Ah , yes, it’s a bit difficult. Alright then, how about Melancholie Galliard, which doesn’t go beyond six strings? I mean, something like that (well, in fact there are only two texts of that piece, one is in the Euing book, which isn’t printed at the moment. And one’s in a Cambridge book).

Basically, what I’d like guitarists to do is have confidence that they can use their own musical judgement about a piece.

But again, this is something that modern musicians have got out of the habit of doing. They’re having to relearn, and for some it’s very painful process. For example, someone was telling me about modern works for violin, where the composer says “Improvise for x minutes”. And many violinists cannot improvise, they start playing cadenzas from a Mozart Violin Concerto, or something.

Yes, we’re not taught to think, musically. It’s terrible, really. But you’ve got to practice improvising, or we’d all be the same. And another comparison which may mean something to some people, is the music we’re playing tomorrow, which is Morley, broken consort music—it sounds as though it’s improvised. In fact, every note was printed in separate part-books. It’s very comparable to Dixieland, and if you hear a Dixieland band, they are actually improvising; but the nett result is about the same. And it just happens that because they wanted to print it in 1599, Morley had to write all the stuff down.

But I reckon that most of the professional players of that time could have improvised in that style. He even says, in the introduction to the book, that the Waits of London (to whom he dedicated the book) were free to improvise, if there was something a little bit weak somewhere.

But we’ve lost that art in classical music generally. We should encourage people to think more musically, and more creatively. It’s not easy to do. And I think we’re just moving towards that, in the lute field.

Really, it’s getting people to help you with stylistic points, and pointing out stylistic things, so that you don’t so something that’s sort of stupid for the music; but at the same time, to have the feeling of freedom, that you could improvise on things. And often, now, I’ll give students a piece for which no divisions exist (there’s a lovely little Holborne Galliard, which is printed in Lumsden’s book), and tell them to improvise some divisions.

Some of them probably go petrified.

Oh, initially, sure. But if you just say, Go and do it in private, but work something out… don’t write it down, though, that’s the important thing, you mustn’t write it down. Just remember what you do, and start thinking musically. If at a student age people start doing that, and therefore get confidence that they can do it, then I think we’re beginning to open it all up, and loosen it up—instead of thinking that you have to play it like this because that’s what the book says. It’s much more important to see what’s happening musically, and free it.

I don’t think it’s just a question of the book, I think it’s more broad—it’s a question of authority. A top-notch flamenco guitarist will seldom play a piece the same way twice, but a student gets a record of that guitarist, and he plays the solo note for note. And not just because he’s scared to improvise per se, but partly because he thinks, What I can do is going to be vastly inferior to what this master has come up with. Then, of course, you get into the habit of not thinking for yourself.

Ah, well, then you’ve got to throw the record away, haven’t you?

That’s right. But it’s the same with Dowland, the student’s bound to think, My little Mickey Mouse divisions can’t compare with Dowland’s. And you lose confidence.

Well, not to worry. All people copied to begin with—I mean, you look at Morely’s madrigals! One of the best madrigalists in English music. You’ll find they’re straight copies of Gastoldi, he learnt his art by copying. And even Dowland did—in Dowland Book 1. You know, Dowland must have been so excited by the music of Luca Marenzio. And his music wasn’t printed until 1588, in England, as madrigals—he didn’t write solo songs. Dowland must have heard it (and how did he hear it? Because it wasn’t printed in score. it was in part books). So he either sang it with people (and he wasn’t a professional singer), or he sat in on a session where people were singing it.

And he heard this and said, Wow, this guy knows how to activate the music emotionally, I’m going to go and study with him. He was 31, he’d done two degrees in music (Oxford and Cambridge), and he jumped on a horse and went down to Rome to study with Marenzio, he was so knocked out by him—that was in 1594.

When he published his first book in 1597, you’ll find the beginning and the end of one of the pieces—Would My Conceit—is almost a note for note copy of Marenzio’s madrigal Ahi Dispietata Morte. And there’s a great composer, already, in the 1590s, learning a new style by copying. Morley did the same. But when you look at Morley’s later work, it’s totally himself—or, he’s taken a Gastoldi canzonet and improved it! He’s not afraid to copy, but then an idea will come to him, and he actually improves the original.

So, I think that’s how people should learn: you copy your idol, even off a gramophone record not for note, to learn the style. And then, you throw away the record and add your ideas; and if you have a musician in you, it comes out.

I agree entirely. I don’t think anyone need be ashamed of trying to sound like their idol at the outset, most great players will cheerfully admit to having done the same themselves. It’s only if you’re still playing that way after twenty years…

Right, then it means you’re a bit crippled.

I think, too, that if you’ve got the talent, you don’t even need to try—you will start playing like yourself, without actually making an effort.

Yes, I think the most useful point we’ve got out of this morning is that one. I agree that for a lot of amateur players, that would be quite a difficult point to take on board, because they won’t feel confident enough to do it. But I think that for the odd one, who’s got something hidden away there, it should be an encouragement, really to strike out musically.

Notes

1Elizabethan Serenade—The Julian Bream Consort (RCA 5687/88)

2English Ayres & Duets—The Camerata of London (Hyperion A66003)

3In a bed (Thomas Mace, Musick’s Monument).

4Stainer & Bell H146.

5Stainer & Bell B487.

6Fritz Knuf.

Discography

With the Julian Bream Consort

| Title | Label | Media | Download |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Julian Bream consort | RCA | Buy CD | ? |

| Fantasies, Ayres and Dances | RCA | Buy CD | Buy MP3 |

Robert also seems to have played bandora on an LP called Dowland’s Vocal Music (HMV CLP 1894), which was reviewed in the April 1966 edition issue of B.M.G. Magazine; but I can find no further trace of it.