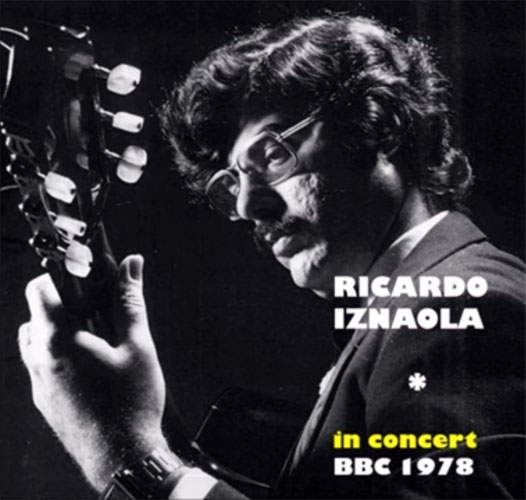

Ricardo Iznaola in Concert

An episode of the BBC Radio series The Classical Guitar, 18 November 1978

Today our programme comes from Saint Helen’s Parish Church, Brant Broughton, Lincolnshire; and we’re visiting, for the third time, a summer school for guitarists organised and presided over by Graham Wade.

As usual we have an invited audience, and later on we shall have one or two questions from members of the Summer School which will be answered by our guest, who began his guitar studies at the age of 11, and by the time he was 21 had twice won the international contest for guitar-playing in Spain. Shortly after that, he gave his first recital in Madrid; and since then he’s been busy touring and recording, both in his own country and abroad. Ladies and gentlemen it gives me a great pleasure to welcome back the Venezuelan guitarist Ricardo Fernández Iznaola. [Applause]

Ricardo Iznaola begins his programme with three studies by Fernando Sor. They are respectively in the key of G major, B minor, and A major.

[Sor: Study in G Major, Op. 29 Nº 23]

[Sor: Study in B Minor, Op.35 Nº 22]

[Sor: Study in A Major, Op. 6 Nº 6]

[Applause]

Three Studies by Fernando Sor. Ricardo, I suppose most European guitarists are brought up, practically, on these early 19th century guitar studies?

Certainly.

Did your early teachers put you through the same kind of repertoire?

Oh yes: not only Sor, but all the classical pre-Romantic material we have from this time, like Aguado, Carcassi, Coste, etcetera, yes.

Yeah; I want… are there any, umm, studies more or less of the same kind of standard, suitable for, let’s say, the first two or three years of playing?

Well Antonio Lauro is actually working on this kind of thing: very interesting, because he’s trying to introduce the student into polyphonic music through a series of studies written in polyphonic style, like small fugues or small canons; and I think he’s pretty well advanced in this.

We all know the Leo Brouwer studies, which are very attractive and rhythmic and perhaps good grounding for some of the things like Lauro does…

Oh yes! and it really fills a big gap. Because the student traditionally is not really prepared when, he, let’s say, finishes his technical education (let’s put it that way) to face the new compositions that are being written at the moment for the guitar. Because of course Sor and Coste and all the rest prepare you to a kind of Romantic or even post-Romantic music; but not really for contemporary music.

Yeah. But before we move on shall we have some more Sor?

Certainly.

And we’ll have in fact the Rondo in C, Opus 22.

[Sor: Sonata, Op. 22: Nº 4, Rondo in C]

[Applause]

The Rondo in C, by Sor.

I gather this past year has been a particularly busy and interesting one for you Ricardo, because apart from all your other things you have your own radio programme with the National Radio of Venezuela and I believe it’s not all together unlike what we’re doing now?

Yes it’s rather a new experience for me, working in mass media as it were, and of course we don’t have the the means you have for producing The Classical Guitar. But besides, it’s a completely new experience in Venezuela, and probably in South America, to produce a programme of this kind devoted exclusively to an instrument, its history, its composers; and so…

Yes. Do you stick just to the classical guitar?

Well, I intended to do many things, you see; and I still do, I still intend to do them. But for the time being I am keeping myself within the limits of the classical world. Because, especially in my country, it needs to be publicised.

Is there any significance in that for a young person who wants to study guitar in Venezuela? I mean, are there music academies where he can study guitar?

Certainly, and there are several very good teachers, including my first teacher, Manuel Pérez Díaz, who heads the faculty of the guitar in the Conservatory. And he is the principal of another school where also the guitarists teach. Lauro, of course, also teaches, and several more.

Yes. This is in Caracas, is it?

Caracas, and in other cities also.

Incidentally, I read a programme note of yours, some time ago, which confused me completely: it said, umm: Venezuelan by birth, born in Cuba!

Yes, well, I left Cuba very very early when I was a child, and I adopted Venezuelan citizenship, which is by birth as it were, because I entered the country very early.

But in fact I believe you live, really, in Madrid?

In Madrid, yes, since 1968.

Yes. Now, a distinguished compatriot of yours lives in Europe as well, Alirio Díaz, of course, who lives in Rome. I wonder why you all leave your countries and live in Europe?

Well, I think you can relate it to the point we were discussing before: I mean, we really don’t have the atmosphere to develop a career in this field, you see, so we must emigrate.

To come back to your programmes: what kind of works do you really prefer, above all, to do?

Well, I like Bach, of course, above everything else. And then I kind of have an atavistic attraction to Latin American music, which I play very often, and especially my own countrymen like Lauro, Carreño, Borges and Ponce and Villa-Lobos.

Well, the next piece is you’re going to play is by Ponce in fact, and in terms of the guitar repertoire it’s a relatively extended work; and it’s the Sonata Mexicana. I believe actually it was inspired by Segovia?

Yes, this as a matter of fact was the first big work that Ponce wrote. And Segovia enticed Ponce to write a work of this kind, giving him four titles for four movements: the first of which was The Little Dance of the Mexican Scarf. The second was The Dream of the Ahuehuete, which is a typical Mexican tree. The third was an Intermezzo Tapatío, which comes from a region; and then the last one: Songs and Dances from the Old Mexicans.

[Ponce: Sonata Mexicana]

[Applause]

The Sonata Mexicana by Ponce.

Well, perhaps now we could have the questions from some of the members of Graham Wade’s Summer School.

The first one we have comes from Linda Kerr.

Do you think that South American guitarists play the music of Villa-lobos, Lauro and Barrios better than European guitarists?

I don’t think it has anything to do, really, [with] where you are born: it’s a question of your natural identification with the type of music you play and with your musical training and the general approach to this kind of rhythmic music. But it really doesn’t matter where you are born—in my opinion.

Having said that, I think that sometimes we—at least, I should say I—have the impression that many South American guitarists have a sort of a certain extra flair that we don’t always manage when playing Venezuelan music.

Well, it is possible; and of course it’s evident that long contact with certain types of rhythmic formulas and so [on] make them like inborn. But it’s a question of, I think, training, of one kind or another.

Well, our next question comes from Graham Wade.

What are your opinions on the present state of the guitar repertoire? Is it really as impoverished as some critics believe?

No. The thing is that we have we have some holes in our repertoire that other instruments don’t have. For instance, we are lacking in good Romantic music: like someone said, we have jumped from Tárrega to nothingness. Really good impressionistic music we don’t have. I mean if composers tend to treat the guitar like an impoverished instrument it will continue to be one, you see. So the problem is looking to the future I think, not into the past.

Another question, from John Bradley.

Do you have any special method of learning new pieces? If so, could you explain how this method works?

There is a school of teaching which I think was begun by Karl Leimer, a German pianist and teacher, which emphasises mental work without the instrument. I mean, that is to analyse the piece in abstract as it were, without the instrument, and memorising it, so that when you reach your instrument you already have it in your head. But it is not generally employed, of course, and I don’t know if it could be used to any good by a normal human being. But personally I just study traditionally. I use part of this method just until my capabilities tell me not to go on. But what you have to do is study at first very, very, very slowly: that’s the secret, if there is one.

Well, our last question comes from Ted Hartwell.

Both Antonio Lauro and Raúl Borges wrote a lot of waltzes for the guitar. Is the waltz form particularly popular in Venezuela?

Yes it is, as a matter of fact: one of the traditional popular forms of expression of the Venezuelan popular composer. Of course, it was introduced from Europe in the late 19th century when the waltz was so popular in Europe. It went to America, not only Venezuela but all of South America, and it took some peculiarities, especially rhythmically, from the Negro influence so present and so alive in popular music in South America.

So the mixture is a rather interesting one, and as a matter of fact they have created a new form of popular expression, which is the Venezuelan or the Peruvian or even the Argentinian waltz, with its characteristic rhythmic syncopation and so on.

Yes. Well, Ricardo will go back to some music now, and in fact you’ll probably be glad to know that Ricardo is going to continue his programme by playing some music from Venezuela. And the next piece is Aire de danza by Inocente Carreño, from his Suite criolla.

[Carreño: Suite Criolla: Aire de danza]

[Applause]

Aire de danza by Inocente Carreño.

Carreño is a contemporary composer?

Yes, he’s quite young actually, he must be in his early 50s now.

And is he a guitarist?

No, he isn’t, he’s a symphonic composer who has only written this particular suite for the guitar that I know of. He hasn’t done anything else for the instrument.

Not even with guitar and orchestra?

No, no.

And how about… the next two pieces you’re going to play are indeed waltzes, by Raúl Borges. Now, is he a guitarist?

Yes, he is already passed away. He was the founder of the first guitar academy in Venezuela. He was appointed Professor at the Conservatory, and he was a very valuable personality, because he was self-taught, completely self-taught, with very old methods.

So he did a tour of Europe around 1930 or something, and he discovered that there were new methods of playing the guitar, which unfortunately were too late for him to learn, so he began teaching the guitar according to these new schools: Tárrega school, which he just knew theoretically. He didn’t play like that, he couldn’t, and he formed pupils like Alirio Díaz, for example, and Antonio Lauro, and my own teacher Pérez Díaz. So he was…

…mmm, a very significant man.

Well, perhaps now we get to finish the programme: here are these two Venezuelan Waltzes by Raúl Borges.

[Borges: Venezuelan Waltz 1]

[Borges: Venezuelan Waltz 2]

[Applause]

Two Venezuelan Waltzes by Raúl Borges, and they bring to an end this edition of The Classical Guitar, which has come from Graham Wade’s Summer School for Guitar in Brant Broughton.

I’m sure we’d all like to thank the Rev. Robin Clark for allowing us to use this truly beautiful Parish church of St Helen’s, and of course I’d like to thank our guest from Venezuela, Ricardo Iznaola, for playing and talking to us.

So until next time, goodbye.

The Classical Guitar was introduced by Michael Jesset and produced by Alan Owen. Our next programme will be broadcast on Saturday 16th December at 6.35 pm.