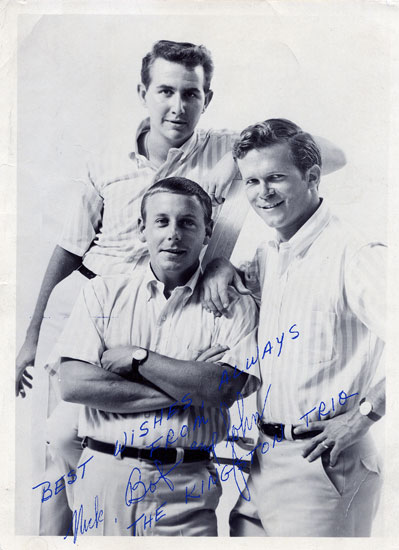

Nick Reynolds (of The Kingston Trio)

interviewed in 1987

To Americans of a certain generation, the Kingston Trio need no introduction: between 1958 and ’63 they caused what Doc Watson later called “The Great Folk Scare”, revolutionizing popular music and setting records (four albums in the Top Ten at the same time, for example) that were unprecedented.

If you’re not an American, or not of that generation, then their Wikipedia article is an excellent introduction, and it would be superfluous to repeat the material here.

But the Trio also polarized people, especially those who have been referred to as ‘folk purists’ (see, for example, Wikipedia’s Initial criticism) section.

For myself, I was always a huge fan (the first three albums I ever bought were the Trio’s); but though they opened the gates to a whole new musical word for me (and I still listen to the old albums regularly), I was still able to see the force of some of the objections1.

Their strengths were several.

Primary among these was the way their voices blended, distinctive though they were. But each was also a very effective instrumentalist2 (although when interviewed they were typically modest about this), and their arrangements could be superb. In addition, the sheer variety of their material has seldom (in my opinion) received sufficient credit: they sang songs from all over the world, in English, Spanish, Hawaiian, Tahitian, (simulated) French, and even African languages.

Their model for all of this was of course The Weavers, and Pete Seeger in particular. But it was the fate of the Weavers, blacklisted into extinction for their political songs and activities, that caused Capitol’s paranoia about such things (as well as, of course, all sexual references3) and thus, ironically, paved the way for the later success of Peter, Paul and Mary.

The Trio’s first incarnation (Nick, Bob Shane and Dave Guard) came to an end in 1961, when “musical and personal differences” with the other two (but apparently with Bob Shane in particular) caused Dave to leave4.

He was replaced by John Stewart, a former fan whose song Molly Dee they had already recorded, and whose voice—although it was quite different from Dave’s—also blended well with those of the other two.

John was, in addition, a talented and prolific songwriter (plus the shift to his material conferred the additional benefit of voiding any complaints about ‘authenticity’), and the new configuration initially enjoyed as much success as the previous one.

But the British Invasion was to shift the whole American zeitgeist away from that style of music; and though they maintained, as ever, a significant loyal following, the group saw the end in sight. In 1967 they disbanded. John went on to a further career as a performer and songwriter; and Bob decided to carry on, buying the name from the others and recruiting new musicians to fill their places.

Nick retired to Oregon, to raising a family, ranching, and financing motor racing. But in 1988 he rejoined the Trio (incidentally giving me, an Englishman, my first chance to see any incarnation of the group live).

It was, however, when he was the special guest at a concert of John Stewart’s, in March 1987, that I had the chance to ask Nick for interview, for Guitar International magazine. Unfortunately, however, this was one of several that were never used; and so it sees daylight here for the first time.

Sorry about the profusion of endnotes, there was just too much material to cram into the main text.

For the sake of completeness I have included our discussion of the availability of the Trio’s material on CD; but it is of course now well out of date: see the Discography at the end.

I hear there’s been a revival of interest in the music of the Trio. Is that correct?

Well, in the Trio and this type of music… as John said last night, we did a Peter Gabriel number in the show; and folk music is being written as we speak. People consider them Rock ’n Roll artists, people like Sting, and Peter Gabriel; but they’re basically folk writers—I mean, a lot of their stuff.

Well, it depends on what you mean by folk music…

Well, OK, you could start with Sting’s Children’s Crusade, which could be done by a chorale, or it can be sung like John does (John and I are going to do that). Or Solsbury Hill, which we sang last night: it’s sort of a semi-rock thing, but the lyrics are folk; meaningful lyrics.

So I think the folk movement, even though it comes in different guises—Peter Gabriel, certainly Paul Simon—is around, and very healthy.

Now this brings up [the question of] how it evolved; and it really all started with the Trio, as far as making it an accepted form of commercial listening. And although we were very simplified (you know, three or four chords), and very easy harmony (sort of a do-it-yourself kind of thing), a lot of these people (I’m not saying the ones I just talked about) picked up their first guitars because of what we did—we were five or six years ahead of anybody else.

Actually, even now, it doesn’t seem so simple to me. I mean, the thing that distinguished the Trio from everybody else in the early days was that while everybody else was just strumming three chords, you had good guitar arrangements, with melodies and counter-melodies and the rest of it. And I know you’ve been a big influence: I think Lindsey Buckingham, of Fleetwood Mac…

Oh, yeah, he learned to play the guitar note for note off all of our albums, every chord, every lyric… when John and I recorded an album a few years ago, called The Revenge of the Budgie, (which was sort of a mini-album that we did) it was basically a duet album; but Lindsey would help produce, and just sort of hang out. So we would do a take, and then we’d sing three or four Trio songs in the booth while we were rewinding it. And it was really nice, because some of these people were coming out of the closet: before, it had been very unhip to be influenced by three squares, supposedly collegiate…

Yes, when folk music really got going, there was kind of a backlash… everything had to be authentic, and if you weren’t authentic, you were no good…

But everything had to be highly arranged musically; and that’s OK, because everything we did was so simple that people did get interested in it, picked up their guitars and went a thousand steps farther. We were pretty well stuck in our modus operandi; because we’d sold so many millions of albums, that people wanted to hear it the original way it was done. We couldn’t change, we couldn’t expand, and still be making a living at it. I mean, we could have progressed slightly; but basically, they wanted to hear Tom Dooley with two chords, they wanted to hear M.T.A. with three chords…

Since you mention that: I’ve been told that was the basic musical difference between you and Bobby and Dave, is that right?

Dave wanted to expand, electrify (which at that time, before anybody had done that, would have been a real innovation, because everybody was playing acoustic). And he wanted to get into more bluesy things, Rhythm ’n Blues… and Bobby and I just didn’t think it was appropriate for fairly affluent white boys to be singing Rhythm ’n Blues—I mean, there are certainly enough people who are qualified to play that, and rightfully so. And it was huge then, and it’s huge now, and getting bigger all the time5.

I have several beefs, and one is ‘replicars’, like people who take a good MG design and put it on a Volkswagen chassis; so even though it looks like an MGB, it’s just a piece of junk. And going out of your natural venue and singing things that… if the Trio had done things like Working on the Chain Gang, it wouldn’t honestly have been the Trio, to do that.

Although of course you did take music from all around the World…

We took music from all around the World, we did some Gospel tunes and stuff like that, but not with the voicings… we used our own voices, we didn’t try to do the accents and be something we weren’t.

There is a dilemma there, isn’t there, because…

Dave wanted to do that, tremendously, he wanted to, you know, be a white black group. And it just didn’t ring true to Bobby and me.

But of course there are some cases, like dialect songs, where if you don’t do the accent the lyrics don’t rhyme any more (especially with Scots stuff). But if you do do that, then it’s an imitation. For example, Roddy McCorley, which you try to do with a slight Irish accent, on College Concert…

Right, but only because we’re such good friends with The Clancy Brothers… you know, it gives a little feeling, and it’s a little more legitimate, because we hung out with them so much and sang with them so much we picked up Irish accents. We had an awful good time with those boys.

I’m sorry, I need to cover some stuff you’ve been asked half a million times…

How did you get together in the first place? Let’s see, Dave and Bobby were from Hawaii, right?

Dave and Bobby were from Hawaii, and I was from Southern California, and I ended up in a little school down on the San Francisco Peninsula called Menlo Business College (I’d flunked out of several other schools and finally got in there). I met Bobby Shane, who was there; David was at Stanford, about two miles away: he was the brains of the outfit, and a very studious man.

And a real genius, and real crazy—all of us were real crazy, you know, we came on looking very clean-cut, but it was not all that true. We had an awful lot of fun, doing everything.

So Dave and Bobby had known each other from Hawaii, and had sung Tahitian songs, E Inu Tatou E, lots of Tahitian and Hawaiian songs…

Excuse my ignorance: is the Tahitian language the same as Hawaiian?

No, Tahitian has got more French influence.

So Hawaiian is a different language?

As far as I know… I’m not an expert on this. Hawaiian music is entirely different than Tahitian—it’s not as guttural, and the harmonies are different.

Hawaiian music and Mexican music are very similar; and I was born right around the border, so I was hanging out in Tijuana; and we’d go in, as kids, and sing with the Mexican groups. I have I real good ear for harmony, due to my father and my family, they all have perfect pitch, and they wouldn’t even let me sing with them.

But I know about close harmony, it was the Barbershop influence, and I could hear the different parts: fifths, thirds, ninths, sevenths, whatever… if you get more than one or two people singing, you can slip in a part somewhere.

So we got together and played around Stanford, played the local bars: I was a bartender in a little beer-pub. A couple of nights a week we’d play in the beer-bars. Bobby and I would play everyplace, he had a guitar and I had a bongo. We’d come up to San Francisco and leave the stuff in the car; then we’d go into the bar and have a couple of beers in the afternoon, and then Bobby would say “Do you mind if I bring my guitar in and play?” And the guy said “No, that’s OK—there’s nobody here”

So we’d start playing, and all of a sudden the place would start filling up… And we were in seventh heaven: we were getting free beer, and all the pretty ladies that could possibly walk into this beautiful bar on the pier…

Sounds great. Would that be at the old ‘Hungry i’, or was that later?

That was earlier than ‘The Hungry i’. You couldn’t just go in and play at ‘The Hungry i’, or ‘The Purple Onion’: those were the established night, for the avant garde.

There were some great groups that played ‘The Hungry i’: a group called The Gateway Singers, just about the best folk group I ever heard in my life (The Weavers are my absolute favorites).

Yes, you can see the Weavers’ influence in the Trio’s arrangements, with the two guitars and banjo.

Oh, absolutely, and songs like Wimoweh… When we first started out, our repertoire consisted of half Weavers, half Harry Belafonte; because I played the bongos and conga drum at that time, and that was about all until I picked up a little tenor guitar.

Yes, how did you come to play that? Because for ages I didn’t even know what instrument it was…

Right. A lot of people still don’t, they think it’s just a big uke.

Which it really is, I tune it like the first four strings of a guitar.

Dave was just learning to play the banjo (he got one from my father, who had one hanging out in the garage or something like that). But basically it was two big [Martin] Dreadnought guitars, and I was playing the bongos.

And then they said, “Nick, we really need some other rhythm on some of these songs, other than just using the conga drum on all of them, or having you stand there with your arms behind your back, singing into a microphone.

I knew how to play the ukulele; and they said “Let’s take a tenor guitar and use it as a rhythm instrument”—which means you capo up to the 7th or 9th fret, and I would play real fast rhythm (rather than add another guitar, which would just muddy it up, being in the same register).

So I would do that. And for a lot of the excitement, a lot of the rhythm, I was the drummer—basically, that’s what I was.

And it worked really well, it had a very distinctive sound.

So it started really taking off for you about… what, ’58, ’59, I guess, right?

’58, I think, the first album came out; and on that was the song Tom Dooley.

We’d been playing at ‘The Purple Onion’ in San Francisco for eight or ten months. And we were the fair-haired boys in San Francisco: we packed the place (it was a tiny little place), but we were sort of the town pets.

And they recorded us at Capitol—they didn’t know quite what we did, but they knew we were being successful at it, so they said “OK, come on down and record.”

The album took (I think) two or three days to record, because it was stuff we’d been doing in the show. There was just one big Telefunken mike for the vocals, and one instrument mike—no overdubbing, monaural…

We were all, you know, really excited, to have an album, with your picture on it, you can send it to your mother…

It came out when we were in New York. And nothing happened greatly to it. We did a lot of promos, disc-jockey’s interviews and stuff…

Finally one of the disc-jockeys up in Salt Lake City started playing Tom Dooley off the album, and called our manager and said “Wow, get Capitol to put this out as a single, it’s a smash hit, it’s number 1 on our chart.” And this disc-jockey called some friends in Seattle, and down in Texas, and they started playing it

Capitol just said “Oh, man, it’s just a fluke, you guys are just wackos, you haven’t been to the city in a long time.”

But Capitol said, “OK, they want Tom Dooley, but we gotta have a hit song on the other side if we’re gonna release it, so they can switch it over and play the other side”

So they wrote some corny song called Ruby Red. And we were back in New York, and they said “OK, if you record this song, we’ll think about putting it out”.

So we needed an arrangement (we were working at the Village Vanguard at the time), and we’d gotten to know Freddie Hellerman (of the Weavers) quite well. We said “Freddie, can you just arrange this thing for us real quick, so we can get it out of the way?”

So we went over to Freddie’s house, and he made this little arrangement. And it worked out, we recorded it and they put it on the back side of Tom Dooley (but they thought it was going to be the front side).

(This is just a little anecdote: they called Freddie and said “How would you like to be paid? Would you like a fee, or would you like a percentage of the record?”. And Freddie said “Oh God, send me a fee, a hundred bucks”. He could have made three quarters of a million bucks if he’d taken a point or two on the record…

But it’s sort of a joke with us now, Freddie being one of my real good friends, and one of my great heroes.)

It’s a strange sensation, isn’t it, meeting your heroes for the first time?

I know it. Well, it was great, because how we met him was… first of all, he was like a god to us, anybody in The Weavers. We’d seen The Weavers a couple of times in concert, and they just blew us away (we had all their albums). And we were playing at The Village Vanguard (a little jazz club down in the Village, which is famous for all the great jazz they’ve had there).

And in walks Freddie Hellerman with Mary Travers. She was in an Off-Broadway show, singing some kind of background with Mort Sahl, they had kind of a little chorus…

I immediately fell in love with Mary, all of us did…

This was way before Peter, Paul and Mary, right?

Oh God yes, I mean years. I was thinking, they’ve just had their 25th anniversary, and we’ve having our 30th, so we were doing it for five years steadily and made it real popular, and it made a platform for other people to perform (because up until that time there was nothing going on, except in little pockets like Greenwich Village; and there was no money involved at all in any of those things, there would just be people that would get up and sing, and get five bucks).

But now all these people were going to work, they could make, you know, a couple of hundred bucks a night, or five hundred bucks, and they all started really emerging: some great singers, all over the country. But now they had a platform: folk clubs opened, all over, every city had its folk club.

But we were at it five years before anybody else was; so we got the jump and capitalized on it; and then they took it a step farther, and we were getting tired, tired of doing the same things; and I said “I’m getting out, I’m going to go to Oregon for twenty years”.

Yes, John was saying last night that you have to move on. But of course, the artist and the audience move at a different rate: because they may not have heard a song for a year, whereas the singer may have done it every night for the last thousand, and be bored out of his brain with it.

Oh yeah, really!

How did you do the arrangements? Did you work those out between you, or…

That was all between us, yeah, they were all head arrangements—the whole history of the Trio’s been head arrangements, very little written down.

For a while Dave was writing out some things, and playing the harmony parts on the piano… At that time the record-marketing business was a lot different than it is today: we had to put out three or four albums a year—and work over three hundred days a year. So we were rehearsing constantly, trying to find new material.

Where did you get that material, in fact? Because the startling thing is the diversity.

People sent us things, we researched old records, in books…

The Library of Congress?

Mostly from obscure record shops and stuff.

For example, a song like The Escape of Old John Webb. Is that a folk song, or…?

It’s a folk song.

Where did you find that? Because I’ve never heard anybody else do it.

I don’t know… Dave probably found it somewhere. He’d be hanging out with these people all the time, and picking their brains, and learning their songs, and then we’d do them [laughs].

Where did you get Tom Dooley, for that matter? Because I’ve heard Doc Watson do it, and it’s very different.

Yeah, well. We were playing at “The Purple Onion” here, and every (I think) Tuesday afternoon they would have an audition, and the owners would come in and these people would sing and play. We were down there rehearsing, in the dressing room.

And this guy came in, with his overcoat on, played about four songs… One of them was Tom Dooley, almost exactly the way we do it. We asked him for the lyrics, and we put in a little harmony kind of a thing…

And that was it: he left, and no one could ever find him again, when they were looking for the true writer of the song, couldn’t find one anyplace.

And there was a huge long court litigation (because we assumed it was a P.D. tune). Years later they suddenly found someone that had the copyright on it; so Dave had to give all the money back.

But it is a folk song!

Oh yeah. In North Carolina, we were heroes there, because that was where Tom Dooley was buried. We were invited down there, and went and visited the grave-site, and his old school; we were wined and dined and moonshined, it really was a great place… we went back there three or four times—did a benefit for a fiddlers’ convention down there.

How long did it take you… like, nobody knows you, and then Wham, suddenly you’re at the top, and everybody recognizes you when you walk into a shop… How long did it take you to adapt to that kind of life?

Well it was really strange, because it happened pretty fast.

The Trio wasn’t like the Beatles or the Stones and stuff, there was not a lot of recognition, or sexual connotations, we were kind of like a unit.

No teenagers chasing you shrieking down the street trying to tear your clothes off?

No, that never happened, not even in our heyday. We were playing mostly to college kids, and in some nightclubs…

But the recognition really came when we got on the cover of Life magazine, back in 1959, I think. And Life magazine was at that time head and shoulders above anything—if you got on the cover of Life, or Time, that was it.

And I remember that very day that Life came out, I saw it on the news-stands in New York; and then I was at Newark Airport, and about ten people came up and asked for my autograph. Everybody bought Life magazine, it was really a big deal.

The album took off after they released Tom Dooley, and college kids just ate that kind of stuff up, because it was the kind of thing where they could sing—it was, you know, real simple, and we’d get up on stage and they’d sing. Then they’d think “God, I could do that”, and they’d go out and buy a guitar. And some of these people are among the greatest writers and players today.

One such thing that occurs to me is America: do you know a song of theirs called Don’t Cross the River? It sounds to me just like a John Stewart song, from his Trio days.

I don’t know it, no. Living up in Oregon for so long, I had no radio…

Really?

I was in sort of a canyon… I had a whole bunch of tapes and records which I would play; but I didn’t buy any new music, or listen to any.

I was going to ask you that: how much have you kept up with folk music, and contemporary singer-songwriters, throughout the years?

Not really at all—just through John. He would introduce me to different people, and… you know, driving around in the car you hear things: for the first time I heard Sting sing, the Police: I was driving up in Santa Barbara with John, and I said “Wait a minute: that’s the best song I’ve heard in the last twenty years!”

It’s funny, I have a good ear for hits. I can remember what I was driving, and where I was going, when I heard these songs for the first time, some of the Beatles’ things… I just pulled over to the side of the road and started crying, or getting weird or something, you know.

So it all started right here in San Francisco in a little tiny club called ‘The Purple Onion’; ‘The Hungry i’ was across the street, and that was the big room in town, supposedly, it seated about 300 people, or 400, I don’t know; but that was where Mort Sahl had been working, and The Gateway Singers.

The Gateway Singers split up—it’s hard with groups, there are always problems. But they had a beautiful black contralto singer, named Elmerlee Thomas; and they couldn’t go anyplace and play with her in those days.

Even here?

They went to Lake Tahoe, I drove up to see them up there, and she wasn’t allowed in the Casino—she was only to use the service entrance.

And Lou Gottlieb was in the group, and a guy named Jerry Walter, and Travis Edmonson, whom I’ve known for years, from the University of Arizona, all marvelous musicians and great voices… in may ways they were better than The Weavers, they were just stronger. Ronnie Gilbert has a marvelous voice, but this gal really had the soul, with a lot of the things that they were doing.

So they just disbanded, got real disappointed… you know, it was hard. They could play ‘The Hungry i’ and around town…

I didn’t realize you got all that crap here, being from England; I mean, I knew you got it in Alabama, and places like that…

Well it’s not like that now; but back then you couldn’t have mixed groups

Doing all these folk songs, did you often get censorship problems with the record companies?

We were a strange group, very commercial (as you know). We had had a discussion as to which direction we would take, which audience we were aiming for. And this was before we even started: we said How political did we want to get? The Weavers had just been blacklisted on every radio station and TV show. We said that we didn’t want to get into that problem, even though a lot of our feelings were bent that way, we kept them off-stage and private. And very quiet, as far as fund-raising and doing things like that, it was never publicized. We did a lot of things, and we didn’t ask for credit, nor did we want any.

We had to censor ourselves a little bit, because we wanted to make it palatable to everybody, which business-wise is a very smart move; because if you get too far out, or too risqué, or too bawdy with a group like we had, which was supposedly a clean-cut type group… you know, people are bringing their kids to see us.

We could have lost half the audience right at the start by saying “I don’t give a damn, I’ll sing the original lyrics”. But we changed them around.

Do you still all get royalties from the albums? Or did you sell the rights?

No. First of all, we bought Dave out: he gets writer’s royalties; but publishing royalties and record royalties we kept in the corporation. Bobby Shane, when he bought the name, relinquished all his rights to any old recordings. So it ended up with just Frank Werber (who was our manager) and myself having all the royalties. But we still get very good royalties from that.

What’s still in print from those old albums?

Not much. But they have a couple of Best of albums, I think there’s two or three.

But the trouble with Best of albums is this that they never are: they’re more like A Representative Selection of.

Yeah, they do that. I had a lot do with publishing: they’ll put on a few ‘best of” tracks, then fill it out with things one of their friends has published.

So they all get a taste, they get as much money from that as from Tom Dooley.

I’m in the process right now of working with Capitol again, in their Special Markets. There are about twenty albums that aren’t in release any more; and out of those twenty, we’re taking about putting out a real Best of, with my help—what I thought was the best, what got the most audience reaction: out of twenty times twelve songs, I’m sure I could pick twelve that were more representative than just Tom Dooley, M.T.A., Zombie Jamboree or whatever.

And so they’re very interested in filling in that project, or even re-releasing several of the albums that have been out-of-print.

But they want to do a CD right away: I think they’re going to do a CD of one of the Best ofs that they have now.

How was Capitol’s marketing in the rest of the World? You were never as big in England as you were in the States; was that their fault?

We had the best audiences of our lives in England, when we went over and played. I was amazed, because our record-sales in England hadn’t been fantastic—they were actually better over on the Continent.

But the audiences are so intense, I mean they’d get as intense as we would get, and they’d listen to everything, and they’d appreciate every nuance.

Whereas over here, although the audiences were great, and we were always pre-sold (you know, if we went to a college gig, they already had all the albums, sang along with all our songs)…

Over there it was just more intelligent—I don’t know what I can say, but they were just fantastic.

John’s very big over there, I hear.

Yes. I’ve always thought being at the level of John, or Gordon Lightfoot, was the best way to be: you’re famous, you have good audiences and a good income; but you can lead your own life. Who really wants be to like the Beatles were for several years, with people trying to tear your clothes off, and break into your house?

So really, I think maybe that’s the best chance you have to be happy, if you’re at a slightly lower level?

Well, that’s the way we were with the Trio. Another thing we did, we stayed here in San Francisco. They were dying for us to come to L.A. and do TV show, and we said No, we’ll keep our offices right here in San Francisco (I lived over in Sausalito, but our office was right here in the city).

That whole thing got too big, with corporations and accountants and lawyers and art departments; and I wasn’t making any more money ten years later than I was when things were hot. In fact we started to make less, we had a whole building full of people, managing, and I was paying all their salaries.

Ando so I decided that I didn’t want to be tricked any more, and I talked to my accountant, and he said, Well, we’ll do it one more year.

John and I had talked, because John and I are such close friends, and I knew he wanted to move on in a different direction. So I said “John, I’ll talk to Frank, and you and I will fade, when it’s reasonable”.

But the accountants said, Do one more year; so we played for another year, almost every night, just to build up some cash-flow. It was billed as The Last Tour, so everybody came to see us, we made a whole bunch of money, and I moved to Oregon.

But we recorded the last two weeks at ‘The Hungry i’, and I have all those tapes—think twenty-seven hours of tapes. and I’m going to edit those, and they’re talking about putting that onto a CD; because it was not only nostalgia, but friends would come from all over the World to see us, and we’d introduce them and they’d get up and play sometimes.

There was a double ‘Farewell’ album, wasn’t there, Once Upon a Time…

Oh, that was supposedly our last album: that was recorded up at the Sahara Tahoe. It was a real good album, and by that time we were producing our own records; and we sold the rights to that to Bill Cosby’s company, which was called Tetragrammaton. But when it came time to get paid, they decided they’d rather go bankrupt; so Bill went ‘bankrupt’, and they sent us our tapes back after they’d sold a bunch of them.

But it’s a real collector’s item, it was really a good album.

As for the last days at ‘The Hungry i’, the few tapes (of the 27 hours) that I’ve listened to are really spontaneous, there’s some pathos… but mostly there’s a kind a relief—it’s like the last few days in the hospital or something like that, looking forward to going home.

Does it seem strange now, looking back on all that twenty years ago? Because you’re a different person now, you must be…

Oh yeah, very much so.

Anyway, that was then. What about now? You’ve left Oregon, so I gather… to get back into music?

Partially because of that: we moved, my wife and I (we have three kids: a five-year-old boy, a nine-year-old girl and a thirteen-year-old girl); and we were really living out in the sticks. And there were problems with the school system, it was without certain budgets being passed, they would just close the school—last year they closed the school for three weeks, and it could happen again this year, and for longer!

So we wanted to get back a little bit into the mainstream, it’s not fair to kids.

It’s beautiful, really, they were all born on the ranch, right in the house, with midwives and me. And it was great to raise kids from zero to maybe seven or eight years old, we had a pretty close unit up there.

But they had no outside influence besides school, the bus trip was their big…

Event of the day?

Yeah; and Southern Oregon’s a very depressed area. We had a lot of friends, a lot of people moved up there in the late ’60s and ’70s that wanted to get away from the urban scene; and you know, make it on their own, have their own garden and fresh water, and fresh air… They didn’t last very long, because there’s no way to make a living up there.

So what made you pick it? Why Oregon?

It was kind of a fluke: after I left, I needed a place to get out of town immediately, to kind of clear my brain. So my first wife, and my son (who was eight at the time) moved out just for two months: we rented a cabin from friend up there, on this beautiful river.

And we fell in love with it (although we had this nice house in Sausalito)… We said, “Can we buy it from you?”, they said “No, it’s in the family”, so I talked to my friend’s father, and he said “I’ll lease it to you for ten years”—a hundred bucks a month, they pay the insurance and tax.

So we all agreed to do that: went up there and fixed it all up, made it really cozy… But my wife split, got cabin fever after about three or four years; and I kept my son up there and put him through school—just the two of us, ‘baching’ it.

And then I bought the ranch next door; and after my lease ran out I built a beautiful house over there, and I remarried, to my friend’s wife Linda; we had our three children.

It was time to get out, though, after twenty years: with this hip surgery I couldn’t carry big clumps of wood any more, and we had to keep two fires burning, all day long, eight months out of the year. A lot of work, a lot of upkeep: the house was becoming a trap, rather than paradise…

So we moved down to Southern California, where all my friend were. In the meantime, John had called me (I’d done the Budgie album with him, and a couple of little projects with back-up singing)… He said “Come on down, and let’s go out! I go out, and whatever we make on top of what I usually make, you got it! We’ll just have some fun.”

Which, obviously, we do, I’m sure you could see that last night. And it also draws from some of the old Trio audience, who wouldn’t come just to John by himself; and the ones that do come to see John don’t mind putting up with my antics…

His material is a lot different now…

Right on! God, I watch every show he does, and I’m always in tears and stuff, I’m very emotional. I think he’s one of the most brilliant… not only writers and poets; but when he’s hot, performing, he’s really hot!

Yes, he’s got the gift not just with the words, but the melodic one as well, which is pretty rare—that comes through in the Trio’s material, as well.

So are you going to start a new career in music now?

Well, this is my career. John has a six-year-old boy and is very involved in the recording business, not only recording his records (he has a studio at home now, so he can record right there, in Malibu). And he has his office there, he’s on the phone constantly.

But about five or six days a month, to pay the rent, you’ve got to go out. Because all these things are a little bit in the future, you know? OK, we’ve got this record deal, but the royalties won’t be coming in for a year and a half. If it hadn’t been for Daydream Believer and a couple of other tunes, it would have been a whole different story.

Yes, that’s a good song. Although I can’t say I’m ecstatic about The Monkees…

Oh, it was great. But did you know that Anne Murray did a good job? It sold millions.

So John got all the royalties for that, and that’s been supporting him, really.

He’s also been going out on the road; but it’s always been a little painful for John, he’s not that crazy about going on the road by himself—this is a lot more fun, we’ve got the whole band, we’ve got the keyboard-player now, it’s really a joy for both of us.

And it’s great for me, because it made me immediately step into another situation—you know I’m not a solo performer, I’ve always been a group singer. And now I’ve teamed with John, and he’s got me going out and singing a couple of solos. Which is fine! They’re entirely different kinds of songs from what John does, but it includes a combination of everything.

The audience that’s there, and enjoys a joke, is going to go out and buy John Stewart albums; and probably Best of the Kingston Trio albums too, whatever’s on the market.

So you’re not going to start a solo career?

Oh no, no, I’m not a solo singer, I just play a little 4-string guitar—I’m basically a little insecure, too, I’d rather have some voices or some people playing along with me.

On the other hand, you probably don’t want to get into rehashing your old hits either?

No… we do enough of those of those… Tom Dooley, M.T.A.… John just made an album called The Trio Years, of songs that he wrote, for the Trio.

He’s one of my very best friends, one of maybe five that I have in the World.

You’re still on good terms with Dave, obviously…

Dave comes and plays, I don’t have constant contact with him. He lives in New Hampshire; he’s teaching music, and guitar, and arranging and doing some record-production up there.

Bobbie’s doing his thing, I talk to Bob once in a while…

But it’s not like John and me; over the years, John would call me up after making a record and say “Can I send you a dub of this record? You critique it.”; because I’m one of the few people that he allows to say one word about his songs. Because once he records it, boy, you’d better not say “Well, if you’d done this, or tried that, it might be a little better…” Don’t ever say that to John!

But I can do that, he trusts me; and if he says “You’re full of shit, Nick”, that’s OK too: at least he listens to my opinion. And he wanted to me to come down and produce some records for him, and just sort of sit in and be the overseer.

All during the Trio years, I was sort of in charge of the harmony, and the feel of the songs, that was my job. Dave would write out the notes and tell us which key to sing it in—he’d write out, in fact, all the notes—

But we’d say “OK, here’s a new song”… Bobbie would be perfect for the lead (he had most of the lead parts), and “Nick, why don’t you sing up here?”. And then Dave had a beautiful ability to fit in a part right in between, he was like the Freddie Hellerman of the Trio. (Freddie never gets much credit for being in The Weavers; but if you hear the old Weavers songs, there’s always a middle part that’s bordering on cacophony, but is perfect for the arrangement.)

Part of the magic of both the Weavers and the Trio, even when John replaced Dave, was that the voices went so well together; because their voices are very different.

Very different; and for me, the greatest fun or exhilaration in my career was after John joined the group, even though we had the bigger success with David, which is a different kind of exhilaration. The kind of thing I’m talking about is actually getting up and singing every day—the spontaneity returned to like when we first started out with Dave; and it continued on for seven years, it didn’t die out in a year.

I must confess the new Trio is not the same for me.

It’s not the same, but they do a real tight show, they’re very professional, and they’ve got two good musicians—certainly better than I was…

I think that’s disputable…

Well, I know [laughs].

I’d like to ask about the sources of some of the Trio’s songs. How about En El Agua, for instance?

OK, we changed the name: we thought it was a P.D. tune; and it actually is a Mexican song called María Cristina, which I had known for years, and which Bobbie and I had sung together. And then we tried to claim the writer’s royalties, until the Mexican Government jumped on us and said “Oh no, the writer’s doing very well in Mexico City!”

But when we did something that was questionably P.D., we’d change the name and write a bridge, and why not let us get the money, rather than somebody who’s been dead for 150 years, you know?

I know you got some stick for that at the time…

Oh, we got a lot! And rightfully so. But, as I said, we were a commercial group; and a lot of it was done through our publishing companies and management companies, they’d make deals with these people, they’d find out who the writers were and they’d get some of the publishing out of it. And any of the Public Domain songs we did, we just split the royalties, you know, Guard/Shane/Reynolds, or Stewart, or…

On the first couple of albums we didn’t know anything about the publishing business—like on the first album, you’ll notice that Dave Guard sings on all the songs; but we split the money.

After we recorded the first album, they said “Now, who do we put down for the writers of this thing? Somebody’s got to be put down as the writer.”

I didn’t know they made any money, we were so naïve. And so we said “Put it all under Dave’s name, because he’s, you know, the leader of the group; and we’ll split the money if there’s any comes in”; which we did, he got 40% and Bobby and I got 30%.

Who was Jane Bowers?

Jane Bowers was a housewife in Austin, Texas—a very far out lady, who wrote The Alamo and several other songs that we did, and she wrote some stuff for Dave… she was a marvelous person, and wrote songs some of which were very popular—we get requests for The Alamo all the time.

One thing in particular I wanted to ask you. You bridged the gap between folk music and popular music. Sometimes classical or operatic musicians will take folk songs and arrange them (as for instance Benjamin Britten did for voice and piano); and from the folk perspective, the results are pretty awful, because the singers are doing vibrato, and other stuff that’s not appropriate. To what extent do you think vocal training helps in singing folk songs? Are there things you need to know? When you hear genuine folk-singers who’ve never had a day’s training in their lives—do you think training would help them at all?

The training that we got—we were used to singing in bars, and if you got a little tired, you quit singing, and that was it.

But when we first started at ‘The Purple Onion’, we were doing three or four shows a night; and we lost our voices entirely, we weren’t using them properly, we were doing it all wrong. Plus we were drinking all the time, and smoking all the time…

So we were put in touch with Judy Davis, a vocal coach who’s worked with Streisand and all kinds of people; and she taught us the placement of the voice, and how to breathe, and things like that… she didn’t try to make us sing better. But we had exercises we’d do to build up our vocal cords.

So it was mainly staying-power, for us. So I really can’t say if it’ll make you sing any better—I mean, it will in the long run, but whether…

Joanie Baez came to us, she’d just played the Newport Folk Festival for the first time with Bob Gibson, we were headlining the show. And we were playing in a club in Cape Cod; she came down there for two days with her parents and Mimi Fariña.

She came up and said “What should I do with my career, what should I do? Tell me the tricks, how do I become successful?” She would just pick our brains for two or three days. And she said “Should I go to a vocal coach?” And we told her [laughs] “I don’t think you need one, Joanie!”

And she said “What should I change? Should I get a manager, should I start working with a Rock ’n Roll band?” We said “Don’t change anything, Joanie! And don’t sign any papers with anybody!” (because she had no manager, she had no one at the time). And we said “You’re so great, there’s no possible way you can fail. You’re doing exactly what you like to do, and you’re doing it so naturally. But don’t sign any contracts—there’ll be a lot of people after you after that Folk Festival—until it’s a legitimate person you really trust”

It’s so exciting, if you’re in the music business, to have somebody come up to you and say “I’d like to sign you to a managerial contract”: you say, “Oh boy, where do I sign?” So you have to just wait around, really, and do what you’re doing: it’s not necessary to sign a bunch of contracts right at the beginning, because if you have the quality, and the beauty of what she was doing, it would come naturally anyway.

Well, she’s been lucky, of course, and you were lucky; but there are a lot of good musicians out there for whom it doesn’t come—or it comes after twenty years of grind.

Well, when we first started becoming very successful, I got really nervous about it: I had paid no dues to speak of, I was from a middle-class background, you know, never had to worry about finances and stuff, my parents supported me through college…

And all of a sudden here comes this adulation, and also the money started coming in. And I felt like I hadn’t done anything: I hadn’t studied music, I hadn’t paid my dues or practice very much, because we were working all day.

And Phyllis Diller, the comedienne, and a great friend (she was playing at ‘The Purple Onion’) said “Just take it for what it is: it’s happening, and it really doesn’t have a lot to do with luck, it has a lot to do with—maybe subconscious timing. But whatever’s happening to you guys, it’s going to happen anyway, and don’t feel guilty about it.”

So I don’t think Joanie had any luck, she’s got tremendous talent! And so she would have made it at any time, sooner or later.

But as I say, the doors were opened by the Trio for folk festivals, and we had, you know, little ones in South Carolina, and here and there; but it became a very commercial venture for these people to put the folk festivals on, and get these people to come and play who would never have been heard of otherwise.

So if I understand you aright: as regards the people who criticize you for commercializing folk music, you feel that you don’t need to defend that…

I don’t need to defend it any more! When Earl Scruggs comes up to you (because he was at the Folk Festival too) and says “Thank God you guys came along! I can work for some money now!” The greatest banjo-player in the World! And he said “I’m used to getting on the bus and making two or three hundred dollars a night, going around with Doc Watson and everybody… And now I can make a bunch of money, and send my kids through college, and do all this stuff…” He said, “Thank God for you guys!”

Those are the kinds of things that make it really worthwhile, as far as the long-term goes, what effect you have.

And he was thrilled, he had no axe to grind. It was the ones who still couldn’t get work, and were still on the fringes of it… it wasn’t questionable luck whether they made it or not: they had the talent, but maybe not the attitude to deal with people. You have to deal with the club-owners, the press, the disc-jockeys, the record-companies, you have to do all that… and man, one bad word to a record company can blow your whole career.

And you’ve got to be reliable as well…

You’ve got to be reliable—you can’t go out and do the first set, and then land face-down in the split-pea soup for the second set, which a lot of them did: they don’t last very long, no matter how talented.

How did you do your arrangements?

Stuff would happen in the studio. Most of the songs were actually arranged in the studio; we’d have the basic idea, and we’d know the chords; but sometimes we’d even have to read the lyrics, which was really a drag—we just couldn’t remember that many songs.

There was one you sung unaccompanied, Guardó El Lobo, remember that?

[Sings] ‘Ríu, ríu…’ Oh yeah, that was great

Beautiful song. I was amused to see that Early Music groups are just getting around to recording that, ten or fifteen years after you did it.

[Laughs]. Dave brought that in, he found it. That was very far-out song, and it was really neat, too.

The arrangement was great…

Dave arranged that, it was a beauty.

You all speak Spanish, do you?

No, not really very well. I can get along, in border Spanish, and I can get things that I want. Bobbie didn’t speak any Spanish at all, but he can mimic it, tremendously.

The Tahitian and Hawaiian songs we did, they just knew those from over there, and off of records, and would sing them.

Speaking of that, let me ask you what languages those are in. Lei Pakalana was in Hawaiian?

Right.

Mangwani Mpulele?

Mangwani Mpulele’s an African song; I think we got that from Theodore Bikel.

Tanga Tika and Toerau?

One of them’s Tahitian, and the other’s Samoan—Toerau, I think, is Samoan.

O Ken Karanga?

African.

That was your big number, I remember, on College Concert…

Right, my drum solo! That was a good album, College Concert.

By the way, I’ve just bought the CD of your 1958 concert [Stereo Concert—Plus], which I like a lot.

CD?

Yes—have you seen this?

Oh, this one that folk Era put out, yes. Where’d you find this?

This was in Tower Records

Oh, that’s right, they just got a distributor…

We were down in El Paso, Texas; and we did a concert, we were playing in Mexico across the border; and their college came over and wanted us to do a concert for them. So we went over on a day off… and this guy came up and said “I’ve just bought this stereo recorder: do you mind if I stand a couple of mikes in front of yours?”

And Frank, our manager, said “No, I don’t want to hear about it, I want first shot if there’s anything on there.”

So we did the first half of the show, and went back and listened to some of the stuff—it just scared the Hell out of us.

It was very rough: he only had two mikes, there was no tie-in with our mikes, or anything.But a lot of it came out pretty well…

And you get the spontaneity in those situations, that you don’t often get in the studio.

Right.

I wanted to ask you about these others. What’s this one [Treasure Chest, ] for instance?

This was some obscure stuff that Capitol had, out-takes, and B-sides of some singles.

Is it any good?

I’ve never listened to it.

Once nice thing about all your recordings is that they’re technically very good, especially the stereo separation.

Well, Voyle Gilmore, our producer, was very, very good at that after he figured out what we were trying to do; he didn’t try to make us do anything, he would just set up the mikes and he’d control the volume.

And of course, like many others, I sat down and tried to figure out the all your guitar parts. Did you ever do that? You said The Weavers were your idols…

Me? No, I never played, I was never a serious musician. Dave did; and Bobbie was more or less like me, with a lot of really natural talent and magnetism.

So what about The Trio Years, John’s album. Would you like to talk about that?

Well, it’s out, it’s on tape. And it’s a group of songs, good ones: Chilly Winds…

So it’s stuff you’ve recorded previously?

Yeah, stuff we recorded together.

That album is one of the things that brought me down from Oregon, because John wanted to do… I think it was about twelve songs he wrote; and there’s a lot of songs that we did on the latter records, up here in San Francisco, that we really weren’t pleased with at all… Children of the Morning… these were released by Decca. And we recorded them up here, but it just didn’t work out: although the rehearsals were great, and the songs were great, we weren’t satisfied at all.

So he wanted to go in and redo these. And he said, “Nicky, would you come up and do the background on these things? I’ll do the solos, and you come in and add the authentic Trio harmony!” And I said “God, yes, I’d love to!”

And it’s been selling like hot cakes—they sold I-don’t-know-how-many thousand dollars-worth of tapes last night (and they make ’em for a dollar, so they made some bucks last night!)

So you expect to be working with John a bit in future, do you?

Yes, that’s what we do now, we’ve been selling out every night!

Notes

1The bottom of the barrel for me personally was a particularly clueless (or naff, to use the British term) version of Old Joe Clark (on Something Special), but opinions will of course vary.

2Dave, in particular, was one of the most versatile banjoists I’ve ever heard, second only to his obvious model, Pete Seeger. Listen to him, for example, on the love song When I Was Young.

3But the Trio snuck a few in anyway, as for instance in the apology at the end of En El Agua, “Sorry, Señor: the border is closed to all sailors without raincoats!” (although I have to say that when I was a teenager, this went straight over my head). For more about this song, see the interview.

4Dave reportedly wanted the group to learn to read music, and to widen its choice of material considerably. The song Guardó el Lobo, on his final album with them (Goin’ Places) may well be a sign of this: it’s a 15th-century Spanish villancico (Christmas carol), sung a cappella except for a tambourine, and totally atypical of their usual style.

Personally, I think it’s one of the most beautiful things they ever did, leaving more ‘authentic’ interpretations in the dust—but then, I’m probably not a typical Trio fan.

5This appears to conflict with Bob’s account in a 2012 interview with Michael John Simmons:

Dave Guard, perhaps stung by the criticism the group received at Newport, wanted to move the band in a more traditional folk direction. He kept insisting that all three members take time out to study the older styles, to try to make their performances more authentic. ‘Nick and I said, “Gee, Dave, it seemed to go pretty well so far,” Shane recalls. “We’re the biggest-selling group in the world.” ’.

Nick Reynolds Discography

With the Kingston Trio

The recordings of the Trio’s heyday were on Capitol, and these are all available on CD, mostly as twofers.

A curiosity was Something Special, one of those perennial attempts by record companies to ‘broaden [their artists’] appeal’—in this case by dubbing in a very-slightly-out-of-tune orchestra behind the Trio’s original recording, thereby adding little except increased employment among musicians. The unorchestrated masters were (finally) released on CD in as Something REALLY Special, and in my view this is a considerable improvement. I have therefore added this entry in the appropriate place.

With the switch to Decca (after Back in Town) the Trio lost the engineering services of Voyle Gilmore, who had perfected their sound. But the Decca recordings still contain some gems, and most are also available on CD. The exception is Somethin’ Else, a poor album produced when they were floundering as to both musical direction and material, and still only available in its entirety on LP.

There has also been a slew of retrospective releases of live concerts, plus of course the usual plethora of anthologies and multi-disc sets.

| Title | Label | Media |

|---|---|---|

| The Kingston Trio/From the “Hungry i” (live) | Collector’s Choice | Buy CD |

| Stereo Concert—Plus (live) | Collector’s Choice | Buy CD |

| At Large/Here We Go Again! | Collector’s Choice | Buy CD |

| Live at Newport | Vanguard | Buy CD |

| Sold Out/String Along | Collector’s Choice | Buy CD |

| The Last Month of the Year | Collector’s Choice | Buy CD |

| Make Way/Goin’ Places | Collector’s Choice | Buy CD |

| Close-Up/College Concert (live) | Collector’s Choice | Buy CD |

| New Frontier/Time To Think | Collector’s Choice | Buy CD |

| #16/Sunny Side | Collector’s Choice | Buy CD |

| Something REALLY Special | Rediscover Music | Buy CD |

| Something Special/Back In Town (live) | Collector’s Choice | Buy CD |

| Nick Bob John | Collector’s Choice | Buy CD |

| Stay Awhile | Collector’s Choice | Buy CD |

| Somethin’ Else | Decca | Buy LP |

| Children of the Morning | Collector’s Choice | Buy CD |

| Once Upon A Time (live) | Collector’s Choice | Buy CD |