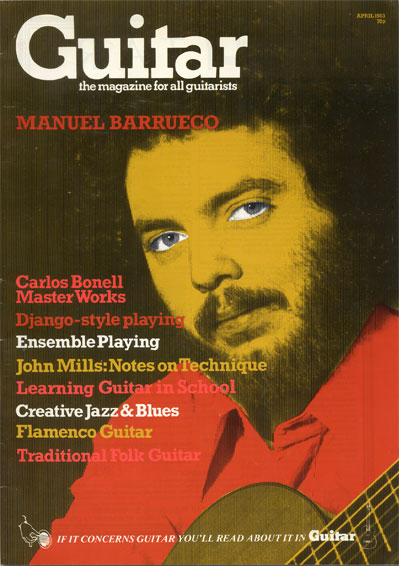

Manuel Barrueco

interviewed in 1983

Few guitarists have made such an immediate impact on this country [the UK] as Manuel Barrueco. The arrival of the first few copies of his records generated astonishment, and his Wigmore Hall début in 1979 caused a sensation. Since then, every visit of his has had the British guitar world out in force, including guitarists who are reputedly known not to go to anyone else’s concerts.

He was born in Cuba in 1952 and started playing at the age of eight. After studying at the Conservatorio Estebán Salas, he went to the United States in 1967 and studied at the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore, where he was the only guitarist ever to hold a full scholarship and to win the Peabody Competition. He made his New York début at Carnegie Recital Hall, and ever since has pursued a career of concerts which have been variously described as ‘awesome’ and ‘electrifying’.

I asked Manuel if he found differences between the audiences in different countries:

I think so. It’s not so obvious between New York and London, but a couple of weeks ago I was playing in Japan and there was a marked difference; people seemed much more reserved. I had a friend who warned me that at the end the applause would not sound very enthusiastic, but it would last a long time; and I found that to be true in most cases. In England, I played outside London for the first time the day before yesterday, in Bristol, and there was a difference again, although I’m not sure what it was. And it varies in the States, too, of course, from city to city. But even though England is not as large a country, still I find the differences. And I remember the first time I came to Europe, I went to Holland—by the way, these are only impressions, I’m not saying “This is the way it is”—it seemed to me that for the people over there music was much more of an everyday event. I think in America maybe it’s not so much so, it’s not as much a part of the roots of the people as it is in Europe—I’m speaking of classical music of course, I know every country and every region has its folklore.

There’s a difference in Rome also, I’ve played there now a few times and like it very much. But before I went I was told that people would be wild, and I found just the opposite; they were very reserved. I almost had the feeling they were sitting back tasting, it was sort of laid back—but every place is different. Here in London I enjoy it very much. First of all, the Wigmore is such a beautiful hall, to me it’s one of the best. And on top of that I get the feeling from the audience that they understand, and they want more out of you; which is something I feel also in New York. I’m sure audiences here and in New York are little bit spoiled. They get to hear many, many people, which is challenge to the player, and I enjoy that. I think it brings out the best in me.

What’s your opinion of the school of thought that says ancient music should be played on contemporary instruments? Do you think the Bach Lute Suites sound better on a Baroque lute, for example?

Well, I like the idea of being as true to the original as possible. And of course if I could hear Bach on the lute, I would enjoy it. But I still like hearing it on the guitar, or even the piano. To me, a lot of the time it depends much more on the player: I mean if you play something from the Renaissance on a double-course instrument, just the sound is Renaissance; but the player, is he a good player? What is he going to do with the sound? And I prefer to hear it perhaps not on the original instrument but with more feeling there.

Are you still using the Ruck guitar?

Yes, and I normally use Aranjuez strings. But right now I’m using Savarez, because I’ve had to play so much recently that I’ve been practicing more than normal, and my hands have been in a constant state of fatigue. So I went temporarily to a lower-tension string.

Modesty aside, everyone agrees that your technique is very good indeed. Is there anything particular you attribute this to? Is it something you were born with, or do you practice harder than anyone else, or do you take special pills…

Well, I always say this, and I’m afraid it will be taken as false modesty, but I don’t see myself as having the technique people seem to think I have; perhaps it’s because I’m much more aware of my weaknesses, and I concentrate more on what I don’t have than do have. It would be much easier for me to tell you what I wish I had more of.

What do you wish you had more of, then?

More technique; but not in the sense of dazzling, in the sense of being able to forget about technique when I’m playing and concentrate on the music. I mean, as I’m playing, many times in certain passages I have to think about technical problems; I wish I never had to. One thing I don’t see very often is people understanding their own technique, and trying to stay within their imitations. It’s something that’s hard to admit to one’s self, and I have this problem that many times I over-extend myself and try to do more than I actually can. So therefore I start taking chances, and sometimes I fall flat on my face.

On the other hand, though, if you don’t try to exceed your limitations, you never push them up.

That’s true. But I studied with Aaron Shearer for some time and he was very good for me, in the sense that he was a very rational man. Before that, I just did whatever felt good, I went by instinct. And then with him, I realized that there was more to it than that.

I want to say one thing that I think is very important. In the past, guitarists in general have been critical of other guitarists; and that is as it should be, because we still have a way to go. It helps the instrument when we take the guitar as a cause. And the improvement in the guitar world has really been remarkable.

It’s still an underprivileged instrument though; in fact, I think the Juilliard still doesn’t have a guitar chair, does it?

That’s right. From everything that I’ve heard, they’re very snobbish: they take the attitude that they’ll have Segovia or nobody. I’ve heard that from several sources.

Are you still teaching at the Manhattan School of Music? Or anywhere else?

No: well, a very little, at the Peabody, where I went to school. I’m going to be doing three masterclasses during the year. But that’s as part of the school.

I’ll be doing the Castres festival in July. I was there last year, and it was a lot of work. I did a solo concert, a concerto concert with the Rodrigo Fantasía and Aranjuez, and a lot of other work including daily classes, and that was a little bit too much for me. Also, when I got there, I thought my concert was ten days or so later, and when I looked through the book I realized it was only four days after, which I found a little bit upsetting. It creates tension, because I have planned my things in a certain way, and I get there and it’s all thrown off. I’m sort of meticulous that way, I like to know what I’m doing so I can plan my time and not have to be desperate.

Do you ever suffer from stage-fright?

You know, when I look at what used to happen to me, and when I see how I can deal with it now, it makes me think that anybody can do it—I was an extreme case. I remember a violin teacher where I went to school, I asked him what to do, and he said the best medicine for nerves was to be prepared; and I think this is so. If you know what you’re going to be doing, and you know you can do it, that’s nice thing to have. But apart from preparation and actual practicing and so on, it’s also the experience of getting out and doing it. You prepare for a concert, you play, and you see what went wrong and how you can prepare better the next time.

I take chances when I play, but sometimes I wonder if I should take less chances, because I’m not sure everything is going to come out.

Is it always possible to avoid taking chances? Take a piece like Aranjuez, for example, it’s so difficult that the only other option is not to play it. Or maybe you find it easy, I don’t know.

No, I don’t find it easy, but by now I’ve played it so many times it’s not all that difficult, although, for a while, I would have nightmares thinking about playing it. But you’re right: you cannot play that piece without a certain amount of risk.

Do you play it exactly as written?

It’s impossible. There are certain chords that are impossible, even if you had the greatest technique in the World. Other than that, I find there are certain little things I have to do in order to be able to play it. Of course I try to minimize the changes, and I am not one for changing things unnecessarily. And hopefully the changes are not noticeable.

Do you have a favorite concerto?

I happen to like the Aranjuez very much: I mean, it is overplayed, but I think it’s a beautiful piece, and it’s very rewarding in the sense that people also enjoy it. I like the ones by Giuliani very much also, and the one by Richard Rodney Bennett, although I’ve never played it.

Further Information

Manuel’s website, which includes a discography.