John Gilbert

interviewed in 1986

The first thing that comes to mind about John Gilbert sounds like a washing-powder commercial—more people seem to be changing to his guitars than to any other brand. The list of major artists currently playing them includes: George Sakellariou, David Russell, Robert Brightmore, Ben Verdery, Lee Ritenour, Stephen Funk Pearson, David Leisner and David Tanenbaum, to name only some of the better known; and Eduardo Fernández and the Assad brothers have guitars on order.

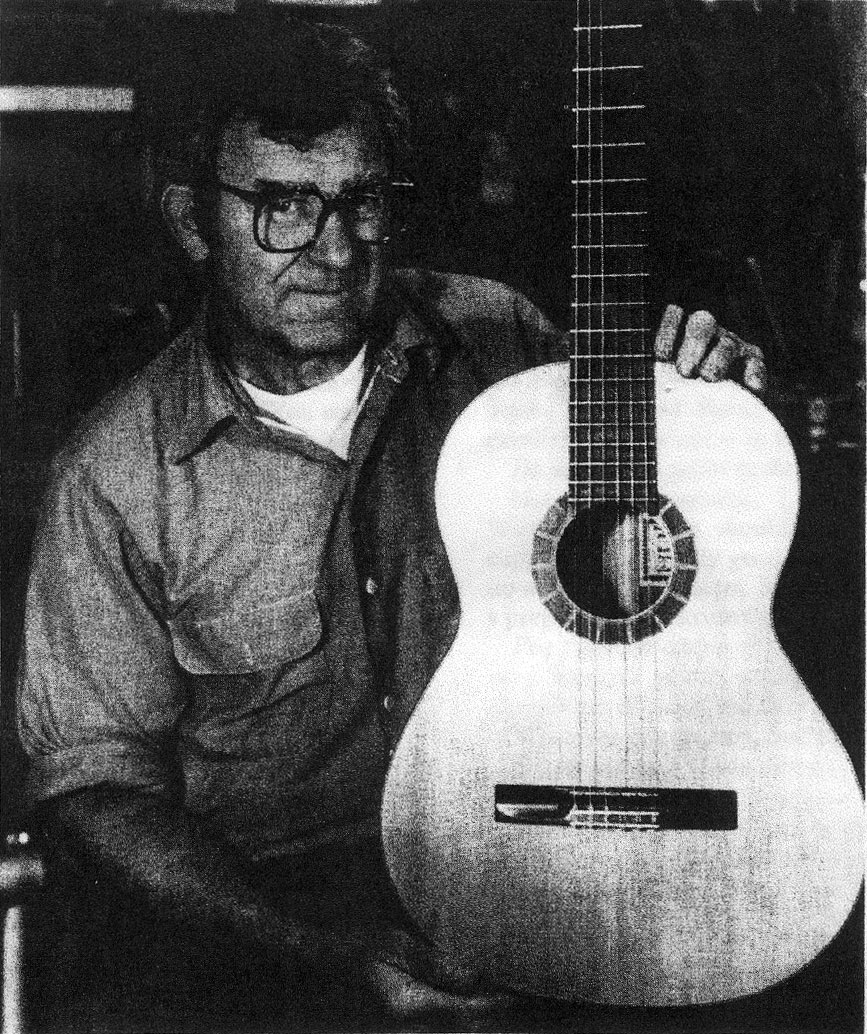

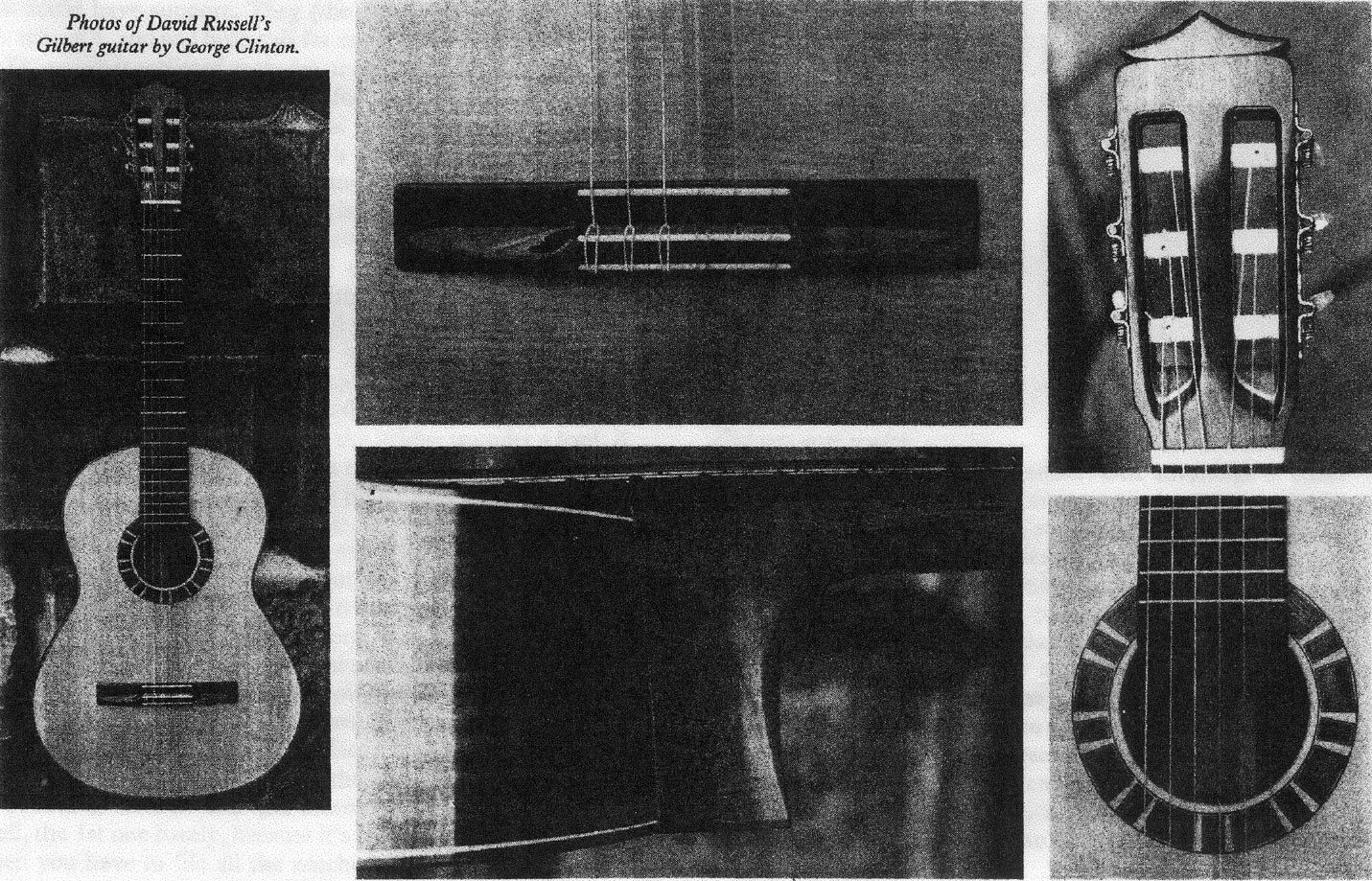

When David Russell first invited me to try his Gilbert, some time ago, I was very impressed. But playing it was an odd sensation: I found the guitar to be almost too sensitive—and loud! I had to make a considerable mental readjustment to get my best out of it. But looking at it the other way, it makes many other guitars seem unresponsive. The sound was very clear and neutral; and I could see immediately why the word is spreading so rapidly. (Not the guitar for a beginner, though, even a wealthy one)! There were several unusual construction features, too, most obviously in the bridge; and it was evident that John would be a very interesting person to talk to. When a trip to California presented itself, therefore, I made finding a chance to meet him a high priority, and a phone call brought an invitation to come and spend the afternoon.

John and his wife Alice live in Woodside, about an hour’s drive South of central San Francisco. For the last few miles you are travelling through magnificent scenery, up into the mountains. The workshop is in a converted garage. I found John to be uncomplicated, charming, and (refreshing in these days when most people are moaning about something), obviously happy. Like many, he was drawn into guitar-making initially as a hobby…

It was in 1965. I'd been an apprentice toolmaker with Sperry Gyroscope in New York, 1941. Then I was in the Service for over two years, but even there I was still doing machine work. I stayed on as a toolmaker for about 12 years, I guess, and then I became a tool engineer. I finally became Chief Tool Engineer for Hewlett Packard, in the Computer Division. The first day of the job with Hewlett Packard, I was going to familiarize myself with the plant layout. So lunch hour, I started to walk around. And as I was walking through the Assembly area, there was a guitar in the corner. So I walked over and picked the guitar up to take a look at it; and the owner walked in. I introduced myself, and he said “You like guitars? I just built one.” I said “How did you do that?” He said “Oh, from England, there was this little blue booklet put our by this fellow…”

Make Your Own Spanish Guitar, by A.P. Sharpe?

Yes, that was it. So I said, “Can I read it?”, and he said “Sure”. He brought it in, and I sent for one, three dollars. This shop [indicating the workshop] didn’t exist, it was like an open car port. And I mounted this bench in here, that was all I had, no machinery. And I built the guitar—it's still being played, I gave it to one of my daughters. Eventually she wanted to buy a car, so it was sold to this fellow for $250.00.

It’ll probably be worth a lot of money eventually.

Yeah, that's what the guy said to me, he said would I put a label in it, with “Nº 1”, and sign it? I said, “Sure, it's my guitar”. And I did.

I believe José Romanillos also got his start with the A.P. Sharpe book.

He’s a fine maker, my hat’s off to that man. He’s built some beautiful guitars. He’s an honest maker too, I always consider him a real honest person, just reading the stuff he’s quoted as saying… it always makes sense. Some of these guys talk baloney. But in my case, I was completely self-taught, and all I had to go on was this little pamphlet. You read this stuff, it says “Never put a brace under a bridge, it’ll ruin the sound”—that’s a load of rubbish. I don’t know where these people get the stuff. And it’s published, and so many people read it, and they say, “Oh, it must be Gospel, it’s in print”.

That’s one advantage of being self-taught, I ignore all the rules—when it says “You must use 3 struts”, “You must use 9 struts”, “You must do this”. Do anything that works for you. Try.

I used to build my guitar very much like Fleta. And I had a maker visit me here, who said “You’ll never build a good guitar with 9 struts”. And I thought to myself, “You should have told that to Fleta”. (Although I gave it up finally, I’m down to 6. I’ve tried 5, and I was willing to try 4). I saw a 3-strut guitar once, beautiful sound. I repaired one once with no braces—it was made in Brazil. It just had a little plate underneath the bridge… it had a very nice sound to it, the tone color was just fantastic. But no volume.

That was when I was repairing. When I first started doing this as a hobby, I used to put fingerboards on for free, do free fret jobs, anything—as long as I could work on someone’s guitar. And I’d look inside, study them, make drawings of them, say “Why did this guy do that? Why is it so different?” And finally, you start to see things, and develop your own methods.

Whom else do you admire?

Well, Hauser built some beautiful guitars. And locally we have some fine makers—in this country there’s Ruck, he’s made some fantastic instruments.

Manuel Barrueco plays one, doesn’t he?

Yes—he tried a Gilbert, but he said he was so used to the sound of his Ruck— played all his concerts, made all his albums with it—it was like another arm. He gets a beautiful tone. Ruck himself, I understand, makes far better guitars, but Barrueco doesn’t want to give that guitar up.

I made Eliot Fisk a guitar, too. He played it in Germany. I made him an extra wide neck and all, wider than I’ve ever made, because he’s got incredibly large fingertips. But he didn’t stay with it, I guess he didn’t like it. They’re not a panacea, they’re not everything to everyone.

But getting back to the other makers, Kohno has made some fine instruments. Then there’s Humphrey in New York, he’s got some dandy guitars—Alice Artzt plays one. And Rubio has made some fantastic instruments. Incidentally, his harpsichords are supposed to be fantastic. I talked to Valente, the famous harpsichordist who teaches down near San José State. He played Rubio’s first harpsichord, and it was an excellent instrument—in fact he ordered one, so I understand.

Do you have a guitar in the workshop right now?

Not at the moment. I shipped one to Ignacio Rodes Wednesday, so he should get it yesterday or today. He’s supposed to be really good, David Russell says he’s one of the up-and-coming masters. So I’m anxious to get his reaction: it’s a pretty strong instrument.

I’ve played a couple of David’s: I found that the Gilbert is a very sensitive guitar—or, looking at it the opposite way, it exaggerates whatever you do…

Whatever you do, boy, that’s right, you can be in trouble.

So, for instance, if you vibrato… it’s like driving a sports car after a truck, you tend to over-steer…

That’s right. It’s very unforgiving. David’s had six of them. I’m going to build him another one, I’ve got another way of doing things now. I built one for Robert Brightmore, and David said he really liked it. So I said I’d build one for when he comes on tour, and if its what he wants, he can buy it; if not, it doesn’t matter—I’ve no problem selling them.

My son Bill is going to make fine guitars, if he goes through with his plan. In June he’ll be up here, to start his apprenticeship, more or less. I’ll teach him everything I know, but I’ll bet any amount of money he'll make better guitars than I do—he’s got that type of mind, he’s a sharp kid. Mechanically, he’s very sound; he was majoring in Chemistry, but he switched over to History, and that’s what he’s graduating in. So he’s going to build three guitars with me, in the shop, and then he’ll build two on his own, also here. Then he’ll have his own shop set up.

I have so many orders that when people call, I know I’ll never build them a guitar, I just haven’t enough time. And I feel badly about it. For every guitar I make, I get five or six orders, so I’m backed up for years and years.

I keep a list of other guitar-makers, and when people call me I usually tell them to go to one of the other fine makers. There’s a kid down in Tucson, Greg Byers, builds beautiful guitars, very cheap, too. He charges $1,200, which is real cheap for a first-class instrument.

Eduardo Fernández is going to get a Gilbert. He borrowed one, and wrote me a letter saying it was the finest guitar he’d ever played in his life, and could he get one. And the Assad duo want a matched pair. Incidentally, Ben Verdery told me John Williams looked at one of my guitars, somewhere in Spain, and played it for quite a while—half an hour or something like that. Ben said he liked the guitar a lot, in fact he said “It’s so much like mine”. And David Russell heard his guitar and said the same thing. That Smallman must be a fine guitar, Ben and David both said so.

What would you say is distinctive about your guitars? What makes it a Gilbert?

Gee, I don’t know. The strutting is pretty straightforward.

Torres strutting?

Not Torres, no, it’s different… there are little variations that I do.

What about that distinctive bridge?

Well, what it is, basically… the bridge, under a load, wants to go down into the guitar. The rear of the bridge, where the tie-bar is, wants to lift, because of the force of the strings. I studied the usual bridge, and I thought it was kind of ridiculous: where you need the strength, which is on the back and front of the bridge, it’s not there—they’ve removed all the wood from the sides. So that’s how come I designed this bridge.

[At this point John got a bridge and demonstrated].

So this takes a much better load, it’s built like a regular large-scale bridge, you know, you’d have Howe construction, you’d make it a cantilever or a drop-arch, suspension or something…but you’d have support. They [the guitar-makers] remove all the strength, and so I built this for my 12th or 13th guitar.

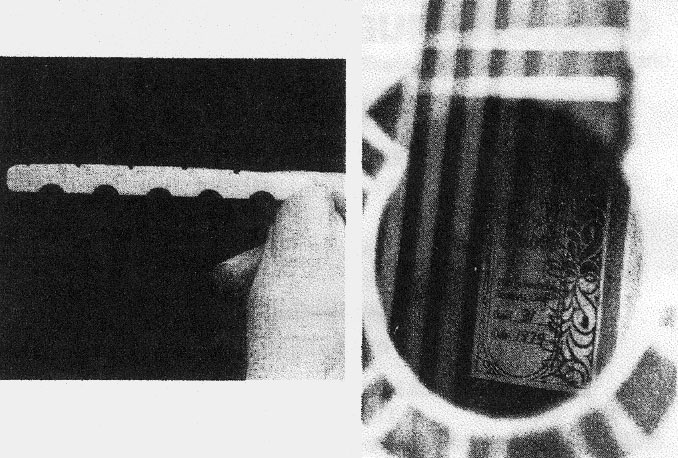

The saddle is scalloped at the top as well, isn’t it?

Top and bottom. The reason for that, Paul, is that, in a conventional guitar bridge, the slot is made with a saw-cut, so you have a flat surface, right? If it would stay that way, you wouldn’t need the scallops; because you’d put the saddle in there, and it would always have intimate contact.

The 3rd and 4th strings are notorious for not having good sound, and people wonder why that is. When I repaired guitars, I used to tell them: “Without even examining your guitar, I’m going to make it sound better, just with what I’m going to do to the saddle. Now you’re going to have real intimate contact for each string, because each will have a foot under it. This web [pointing] is made thin, so it can bend, and can comply with the forces. When the bridge is under a load, it wants to do this [flex]—that means that slot is now curved.

So that’s how I started using the pins that I use currently: it went from an ordinary bridge to this, and then to pins.

For a while, I made saddles out of metal. Feel the weight of that. That’s magnesium—it’s about one third again as light as aluminum, it’s very rigid, and it transmits sound faster than wood, being metal. It worked okay, but it wasn’t the final answer; I don’t even know if the pins are that I currently use. But they are easy to adjust. And you can set the action height of any individual string with ease. For instance: suppose someone wants the 6th string raised. Normally, you would make a tapered wedge to raise the 6th string up, oh, say 20/1000th of an inch. But that means all the strings are raised (well, the 1st one barely, because it’s tapered to a feather edge). Then you have to file all the notches except the 6th because they were okay. So you have to go through all this rigmarole to adjust one string!

With the pins, voilà! You say, “I’d just like to have this string a little higher”. Fine! Just take the string off the pin, lift the pin up by a wafer and put the pin back. It takes less than one minute, I’ve done it for people.

What I like about this bridge is that it supports the face of the guitar, and will give you a much longer life for the instrument itself—it unloads the face. You see, the load is taken up by the bridge, which spreads it out over the whole face. Therefore, instead of collapsing the center, it prevents a lot of the dishing in.

I notice you make your own soundhole rosettes. A lot of people just use the mass-produced Japanese ones.

Oh, yeah, they’re only $2.00 a piece. I used to buy ones from Germany—they were beautifully made—a little more expensive, maybe $3.00 or $4.00, but very precise, very nice. I used them until about my 20th guitar, and then I started to use my own.

Does the rosette affect the sound at all?

Not really. If anything, it weakens the wood, you’re incising into the spruce, which is light, and very stiff. You always put a plate under the rosette area anyway, to stiffen it: because otherwise, it’ll get distorted. And also, you get unwanted vibrations at that very point where the air is rushing in and out, just moving very fast. And you don’t want that soundhole oscillating, you want it rigid. But it’s fun experimenting—I never build two guitars alike, never have.

Except, presumably, the pair for the Assads.

That’s the only exception, because in their case I don’t want one to be better or worse than the other. That way, there’ll be no argument about who gets what.

What wood do you use?

Sitka Spruce.

Canadian?

Yes—I was going to say Washington, but this last board was from Canada. I got quite a number of good guitars from it.

You don’t bother with cedar, do you?

No, I don’t like it.

Did you ever try it?

No. I don’t think I ever will, either. One advantage of cedar is that it doesn’t crack as readily as spruce—its expansion ratio due to humidity is much lower, so therefore there’s less stress on the guitar, as far as breaking it apart goes. The only thing is, I’ve seen some awfully good cedar guitars and (I know this sounds crazy), I wouldn’t want to have to turn my back and pick a spruce guitar over a cedar guitar. I know people say spruce guitars are much clearer and cleaner, but the thing is with spruce, at least the way I use it… as David Russell says, the sound is very neutral, and you can do with it what you will, harsh, sweet or whatever. Whereas a lot of cedar guitars seem to have a built-in sweetness to them—not a sweetness, more of a softness. And it can be very, very beautiful, with certain music. But in general, it’s nice to have the clarity and instant response,

Part of the challenge of guitar-making, though, Paul, is to listen to guitarists—I never set myself up as a judge and jury of what constitutes a good guitar. I listen to what David Russell says, and David Tanenbaum, and George Sakellariou, and all these fine players.

Jack Duarte said to me, “I don’t like loud guitars”, and I thought, “Well, he’s not going to like a Gilbert”—because they’re not quiet, really. And yet he put his foot up on a chair, and played for well over half an hour. So I figured, well, it’s not too distasteful to him.

You don’t make flamenco guitars, do you?

No, I haven’t had much to do with Flamenco. But I went to see Paco Peña’s concert. It was outstanding, one of the finest concerts I’ve seen, for Flamenco. I went backstage to see him, and told him so. Because Flamenco—I don’t know about you, but it bores the hell out of me after a few pieces. But with Paco’s concert—well, we brought him back for 4 encores, but I could have listened to 6 or 8, he was that good. It was so interesting, unlike a lot of flamenco players who just play a lot of flash—completely interesting, from the moment he sat down.

There’s something about the way he plays, I don’t know what it is, something comes through that man. He had that audience right where he wanted them. Perfect evening.

It sounds as if you enjoy what you do very much.

It was like being reborn, Paul.

Starting to make guitars?

Yes, it was. I always felt I was quite successful in my first career: with limited education, making it to become a manager at Hewlett Packard was something in itself. I felt proud of that. But to quit that, and go on to do this full time, and attain a certain degree of success… I feel really good about the fact that all those fine guitarists play Gilberts. So that’s a lot of luck, you know.