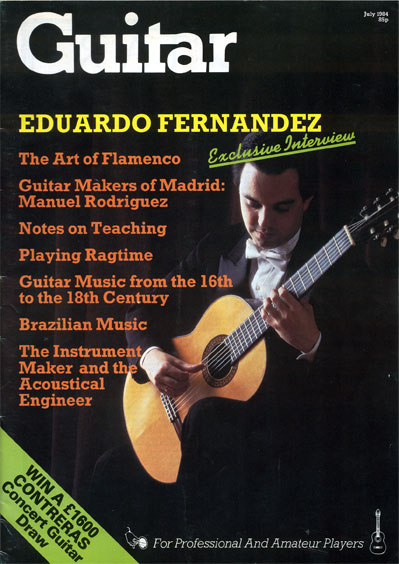

Eduardo Fernández

interviewed in 1984

Eduardo Fernández was born in Montevideo, Uruguay, in 1952. He first gave concerts as part of a duo with his brother; but since 1971 he has pursued a career as a soloist, winning the Segovia prize in 1975. Of his New York début in 1977, the New York times wrote: “rarely has this reviewer heard a more impressive debut recital on any instrument…”, and his London début in 1983 was so successful that Decca immediately offered him a recording contract.

It was shortly after he had recorded two albums for this company that the conversation took place. He proved to have a tremendously wide range of interests, and his English is so good that (despite a slight accent) he is almost bilingual—this is all the more impressive when one considers that he has never lived in an English-speaking country.

I asked him why he chose the guitar as his instrument:

It was sort of a process of elimination. I was always interested in music when I was young, and it was obvious when I was seven or eight that I had to study. I didn’t care much to be dependent on an accompanist, like a violinist is; so it was really only piano or guitar, and I didn’t fancy the piano much… I don’t regret it. I started to study with Raúl Sánchez Arias, who had studied with Segovia in Siena for several years—I didn’t really take it very seriously then. I stopped studying when I was fifteen, but began again a year or so later with Santórsola, doing interpretation, analysis, harmony, counterpoint, everything… he really impressed me very much, I probably wouldn’t be a musician today if it weren’t for him.

Soon afterwards I realised that I needed to correct many things in my technique, and went to Carlevaro, with whom I studied for four years, simultaneously with Santórsola. He turned my whole technique inside out, changed my whole attitude to tackling problems and playing the guitar. I had a lot of problems, pieces I couldn’t play, things I couldn’t get. He made me realise that most of them could be corrected if you thought rationally about them—faced the problem, broke it up into its components, and worked on those parts in a scientific way..

Did you always have the facility that you have now, were you a child prodigy?

I don’t really know, I didn’t have anybody to compare myself with then. My twin brother was studying the guitar at the same period, and we used to sight-read duets all the time. He was very good (now he’s an engineer, he stopped playing the guitar). I don’t know, I never had any problems with speed—probably it was a natural thing. But I never worked towards speed either, never did exercises or anything.

Did you go to music college?

No, actually I was studying Economics at the time, I did about three years of that. And then I drifted towards music. One of the reasons was that we didn’t have classes for a year or so, because the university was under intervention there; and I had already started to interest myself very much in music. I finally found out that what I really had to do was play the guitar. I won a competition in Uruguay, and then the Segovia competition in Spain in ’75. When I returned to South America, Carlevaro said he would put me in contact with the Center for Inter-American Relations in New York. So I got a chance to play there, and that was really what started everything, because I got very good reviews.

You’ve just made a couple of records, haven’t you?

Yes, for Decca, we finished last Friday. One album is mostly Classical, with pieces by Diabelli, Legnani, Paganini, Sor and Giuliani; the other is Spanish, with Rodrigo, Albéniz, Torroba, Turina, Falla and Granados. It took only three days, and it was fun, not at all what I had expected—at least, I don’t know what I expected, maybe a producer with a whip saying “Finish this!”. But it was very relaxed, and the hall had wonderful acoustics. It’s incredible how the technology of modern recording works, it’s exactly like the live sound.

When will these be coming out?

I don’t know, at the end of the year at the earliest.

What do you think of the concert repertory, as it is these days? Do you find some people’s programming unimaginative?

I think it’s more imaginative than fifteen or twenty years ago, but we still have a long way to go. It’s not our fault completely, but the composers’—there aren’t as many pieces for guitar as for violin or piano, not to mention orchestra. That’s getting corrected little by little as important composers like Britten, Henze and Ginastera start writing guitar pieces. It sounds a bit odd for me to say that, I’ve just recorded many of the well-known pieces, but there is also a question of how you approach the pieces—many people play them almost by ear, I think. You have to try and find the originals, go back to the original setting and the intentions of the composer; there’s more to it than just getting an edition by so-and-so and playing it. And I don’t think guitarists play enough modern music. There’s so much written, and one hears so little of it.

Aren’t guitarists (and promoters) afraid that if they play a lot of modern music, the audience will stay away?

You have point there, but that can be corrected, I think, by more exposure. There are two factors here. One is how you play things: if you don’t really like something, you shouldn’t play it, the same as with any other style. But I think we have a duty to the music of our times, there is nothing comparable to the excitement of making the première of a really good new piece.

What examples would you give, then, of pieces that aren’t given enough exposure? Or what composers?

Well, there are many pieces by Brouwer which I think are wonderful. And lots of others. Carlevaro has written quite a lot, and lately he’s begun to compose even more… I’m sure the readers will know many more from the reviews in Guitar magazine; if you live in Europe it’s not hard to be up-to-date with what’s being published, but it’s much more difficult in South America.

What about the earlier repertory? For instance, everybody trots out the same old Dowland pieces.

Yes, and even more so with the vihuela. That’s one of my favourite periods, Narváez, Mudarra, Milán… I don’t mean the things you usually hear, because it’s the same situation as if you only know Für Elise of Beethoven’s—there’s so much more. But how many people play the Fantasías of Narváez? Very few (they’re difficult, too, so there’s a good reason). But you can really play the vihuela repertory on guitar, because there’s nothing to change. With lute music there’s sometimes a lot, because of the extra courses (especially in the Baroque suites), although that can be got around.

Anyway, you have to do some sort of transcription if you play Bach or Weiss on the guitar, but I don’t think that would have bothered Bach. It’s more a question of how you play, have you got the right approach to the style and do you know the style, the ornamentation and so on, the whole attitude that an interpreter would have had towards the piece. Because of course it’s totally different to how we are trained now, to play exactly what’s written, which was not the attitude then.

Playing Bach in the old way, exactly what’s written, with no changes of rhythm or ornamentation, is a bit like a mummy. And once you start to do things the right way, the way historically it was done, it comes alive, and you find yourself in front of a very different piece. The attitude is very important. You could have a superb performer’s edition, with annotation of all the ornaments, etc., but it wouldn’t do to play that with the same spirit as you would with a 20th century piece; because you have to be much more participative, in the sense that you have to collaborate very closely with the composer (which you do anyway when you play, but the composers left a lot more leeway than they do now—well, it’s starting to go back to that situation in some pieces, say La Espira Eterna, you are expected to collaborate. I think the key phrase is that it requires more participation than other pieces.)

A lot of players don’t like that, do they? They like to be told what to do.

If you need to be told what to do with a piece, you have no business playing it: I mean, if a piece doesn’t talk to you and ask loudly Do this and Do that, then it’s because you haven’t got into the spirit of the piece. Until you know exactly what you want to do with it, then you shouldn’t play it.

So what do you think of the old-style performances of Bach, by people like Segovia? Do they turn you off, or do you still feel sympathy for them?

Well, I grew up listening to Segovia, as everyone in my generation of guitarists did. I still like very much the way he plays the Chaconne, it’s my favourite of his recordings. It might be out of style, but who cares? The message gets across, it’s a bit like some recordings of Wanda Landowska: probably nobody plays it like that any more, but she did very well, it has a period charm too. I wouldn’t be able to play like that if I tried, but I don’t reject it. The thing is, how well do you do it? If you know about the period, I think it’s better: it’s more accurate historically, and you do more justice to the piece because you give it the setting it deserves. But it’s not the only way.

The other problem there, of course, is that people tend to imitate famous interpretations, not just of Bach but of everything…

That interpretation is alright for Segovia, of course, but not necessarily for the one who’s trying to imitate. People start copying the superficial features, even the defects. How many people have tried to study a piece in depth, as Segovia does? They just buy the record and copy his mannerisms, which are not really the essence of his interpretation; but they miss the whole message, the spiritual attitude to the piece and the profound reverence that he has.

Yes, I think he said he studied the Chaconne for thirteen years before he played it.

How may are willing to do that today?

Very few.

And it shows when you hear the record, every note is exactly in its place. I really try to do that, to follow Segovia’s example in going as deep as I can.

Who are your favourite composers? What do you enjoy playing?

There are many things I like very much, the vihuela period, for instance, and 20th-century music, everything really. What I try and do in a programme is to structure it so the sequence will have a meaning. That’s what I tried to do last year, for instance: starting with the Martin pieces, which are neo-classical and in a Baroque French spirit (more or less), and then starting the second half with a Tento by Milán which sounds almost as if it were written yesterday, because of the freedom of the structure. And I try to give a different point of view to the pieces by the way I put them together; it takes a little work, but it’s much more interesting to play them that way.

You said something earlier about agreeing with John Williams that the guitar is badly taught; would you like to elaborate on that?

I teach a lot, and I see that most people seem to be stuck at some stage because of their own attitude, which was instilled into them by their previous teacher at some time. They tend to be afraid of the instrument, which is not a healthy thing. I’d also say that they don’t really have the musical background they should have, sometimes they are just limited to guitar music, which is nonsense. You can’t really play Sor well if you don’t know the music of that period, or Giuliani unless you know Italian opera, Rossini and so on; not to speak of Bach, you have to know a lot about the Baroque period if you want to play it correctly. That’s one thing. They don’t seem to be interested in music outside the guitar, they seldom go to a piano or orchestral concert, for instance. I think they are missing a lot, I mean, guitarists shouldn’t be a secret society.

Correcting that means trying to get the guitar into the major conservatories.

But that’s already happened, at least here, and the parochial attitude still exists. Surely part of the problem is what you were saying attracted to you to the guitar in the first place: that it’s possible to play it on your own and not mix with other musicians.

I’ve always thought of myself as a musician first and a guitarist afterwards. When I was a child, for instance, I wanted to be a conductor (I might still try it some day), but I wasn’t really interested in the guitar per se at the beginning. But then it really did pull me in; because I was very attracted to the sounds and the possibilities of the instrument, which are so different from most other instruments. And it’s a challenge, because it’s one of the most difficult instruments also.

So about teaching, that’s one of the problems I see, a lack of musical background.

And I don’t think we’re approaching technical problems rightly either. We try to force-feed technique to beginners and that puts them into what I think is a hostile frame of mind towards the instrument itself. So they get tangled up with a particular problem, and when they’ve mastered it they think “That’s it, now I can play the piece”; and perhaps they can’t, because they have no notion of the musical meaning of it—What John Williams said about many people not being able to phrase properly, it’s very true.

So what would you suggest is the remedy for this?

For one thing, the problem of phrasing a single line well is not limited to the guitar. I think the whole approach has to change, we have to enhance the meaning in music, the communication part of it, more than the physical task of playing the instrument. People must learn to listen a lot more to good musicians, and really get in love with music first, before taking up the guitar or piano or whatever; that would enrich their lives.

Also, I think the traditional approach is not quite right in the sense that it’s a bit like being in front of a wall and trying to demolish it with your head, but perhaps you have a door just one block away. And I don’t think there has been enough thinking.

Can you give some specific examples?

Well, some people try to get speed by practising with a metronome, for instance. I think there are more effective ways to do it (it depends on the piece and the player, I can’t give you a universal approach). Some people don’t know how to hold the instrument properly, they’re tense, and if you’re tense you can’t really make good music.

I remember Julian Byzantine’s saying once that more people have tension problems than technical problems—that is, the problems they think are technical, in fact come from tension.

That’s very true, unless you start at a very late age; in that case you would only be able to get to a certain point. But if you start early enough, say up to thirteen years old, you should be able to vanquish almost everything. For instance, many people don’t know how to practise, they just sit there and stumble at the same place a hundred times—that’s not practising. Or rather, it’s practising a mistake, not the proper piece.

Did you get nervous, or suffer from stage-fright, when you started your career?

No, I didn’t really. For a while, yes, when I was studying with Carlevaro and changing my whole technique (because I was still a bit insecure about the whole thing), but then I got settled again. I do get nervous on the first concert of a tour, that’s always a bit of a torture, because you’re playing some of the pieces for the first time, probably. A piece really gets worked out in performance; you may have practised it a million times and you know exactly what you want to do, but it really gets into shape at the moment of performance.

What other kinds of music do you like, apart from classical?

I’m very interested in some folk music—Brazilian, for instance, Spanish, Flamenco… Indian classical music I like very much, and Japanese too… and perhaps there’s more that I haven’t discovered yet.

That’s quite a range. Japanese music, for example, is a long way from Western music.

Yes, that’s what I like about it. But it’s quite close to some things in contemporary music: because, after all, sound is sound, you can’t get away from that, and music is, you know, meaning made of sounds.

On the other hand, you’ve got a completely different vocabulary, and a different set of formal structures. Can a Bach fugue be comprehensible to a Japanese who has never heard Western music?

Lots of people wrote fugues, but not all of them were half as good as Bach. So there is more to a fugue than the structure: that’s what I’ve been calling meaning. And I think that’s what you should look for. The fact that most people are scared by contemporary music, I think, comes from that, because they don’t listen to traditional music either: they think they like it, but they’re just used to it. They just recognise the vocabulary, they don’t care about going deeper than that. I mean, it makes no sense to listen only to contemporary music. You can’t understand Webern, say, if you don’t understand Bach well—how can you follow the counterpoint, and the rest of it? There are many cases like that, you have to be able to listen to the meaning, not the vocabulary.

Is all contemporary music, then, potentially assimilable by the average person? For example, there are probably some Classical composers you don’t like, even though you know the idiom.

Not really.

There are for me. The vocabulary is familiar, and I’ve listened and tried quite a lot, but those composers still bore me, sometimes to the point where I can’t take more than five minutes. It’s not because I don’t understand the music, because I understand it just as well as Bach or Bartók, however well or badly that may be; it just doesn’t appeal to me, it’s a matter of temperament. Does the same not apply to contemporary music?

Yes, of course, I’m not trying to say that everyone who doesn’t like contemporary music is deaf. What I meant was that, many times, what people think is dislike for the music is just unwillingness to participate in the music. I suppose I see it that way because I’m an interpreter, and you have to try and get into the piece; once you’ve done that, it’s impossible not to like it, at least when you are playing it.

Then again, how much work is a composer entitled to demand from his listeners? Because a lot of pieces do require hard work.

Yes, of course, but the question is, is it rewarding? Listening to a Bartók quartet was very hard when they were written—think of the 4th or 5th quartets. But I think it is rewarding, it’s worth getting the record and listening to it maybe twenty times.

It’s obviously easier for the next generation, too, because they grow up with it.

Yes, but some pieces are never going to be really popular, like some poetry—I can’t imagine people rushing to the bookshops to buy Mallarmé’s poems, for instance, even though they are one of the greatest things in literature. It requires a special turn of mind, like Webern; there is a question of temperament too. But you have to be willing to open your mind a little bit, and sometimes you can be very rewarded.

But of course people who write inferior music will say, when the public doesn’t like it, That’s because you don’t understand it.

In the end, the public makes the judgement, but time makes it too.

Right. When Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring was first performed, there was a riot.

There was a riot, but that was probably more because of the choreography, which was very complicated, and the dancers couldn’t really do it well. Because it was done after that in concert, by Monteux, and it was a success. And riots are nothing new in the history of music.

I remember that Beethoven’s 7th Symphony came in for some stick at the time.

But who knows how they played it then? At that concert, did they really get the message across or didn’t they? One of the problems with contemporary music is that performers don’t take it seriously enough to study and play it really well, and I think it needs a lot more—study, really, not practice—than traditional music does. I mean, everybody knows about Sor, there isn’t going to be a piece that surprises you by the style or the approach; but if you take some Brouwer, you might well be totally puzzled at the beginning. You have to work at it: it took me five years to be comfortable with La Espira Eterna, for instance. And again, you have to be aware of what’s happening in music generally, not only on guitar. You can’t really play that piece unless you know about Ligeti, for instance, pretty well; or Stockhausen, or the other composers.

What are some of your favourite modern pieces?

Well, the Britten Nocturnal is one, that’s a great piece. There are others, the Martin pieces for instance, and the Ginastera Sonata…

Do you think some composers go overboard? For example, there’s a piece by John Cage called 4'33"…

Well, that’s rather an extreme case. It has to happen at a time of transition that many people go overboard, as you say. I don’t mean to give blanket approval to all contemporary music just because it’s contemporary: there’s good and bad, as there’s been in other periods.

Finally, and of course most importantly, Eduardo, what guitar do you play?

A 1975 Paul Fisher made in Rubio’s workshop.

Further Information

Eduardo’s website, which includes a discography.