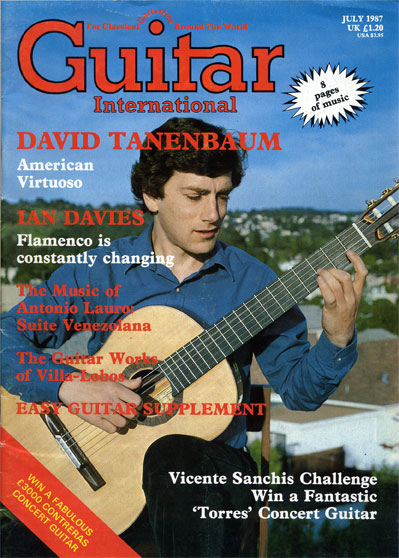

David Tanenbaum

interviewed in 1987

David Tanenbaum is Professor of Guitar at the San Francisco Conservatory, and he has yet to establish his reputation in England; this country, however, seems to be rather in the position of a sandcastle with the tide coming in. Not since David Russell have I heard such consistent praise from other guitarists, and his concerts have received rave reviews all over the USA and a chunk of Europe. Extraordinary talent, incredible technique, refined aristocratic music-making, complete artist, superb sense of style and pinnacle of flawless playing are just a few phrases from the pile I have before me. And not from the Moose Droppings, Iowa Gazette, either, but from the New York Times, San Francisco Examiner and Chronicle, Geneva Tribune and countless others. Not too shabby.

If it were possible to pick one special feature from the general morass of distinction, it would be David’s affinity for modern music, and in particular that of Hans Werner Henze. After hearing David play the Royal Winter Music, Henze wrote to him: “Nobody plays this music as well as you do… I have never heard such a skilful and musically moving performance, and such mastery. I feel very much inspired to write a concerto for you as soon as I have a little time.”

This concerto has now had its European and American premières. The interview was actually done in two parts, one when Henze was mailing the movements to David as he completed them, and the other at the end of May, when the latter was about to depart for Europe to record it, with Henze conducting.

I found David a relaxed individual, with unaggressive but perceptive and well-focused opinions on every subject I raised. The concerto was an obvious topic of conversation, but he is very much at home with modern music generally, having been raised on it—his father is a composer who currently heads the Electronic Music Studio at the Manhattan School of Music, and his mother is a pianist.

My mum says she discovered that I had talent when I was very young, like I was one or two when I started to sing. So she gave me lots of records and I would play them all the time. She began teaching me recorder and reading music when I was three or four, and piano when I was five.

I played piano for two years, studying with her—we used to fight a lot, and by the time I was seven she’d sent me to another teacher. When I was eight I started playing ’cello, and a year later I went to the local conservatory, and took theory and those two instruments.

About a year after that, I started to hit a thing where I just didn’t want to do it any more, it was too much activity; and I started to blow my recitals pretty badly. I remember thinking that the one thing I didn’t want to do was perform music for people, I just couldn’t stand it.

So when I was about eleven, my parents had a meeting with the head of the conservatory, who suggested they give me the option of quitting. And he said “Leave him alone for a year, don’t do anything—he’s talented enough to go back to it on his own”.

So they left me alone (although I think my dad was champing at the bit the whole time), and I got into other things, and picked up folk and rock guitar. And Lo! and behold, the day the year was up, my dad said “I’ve worked it out with this local guitar teacher where he can teach you some rock guitar”. So I went to this guy, and about a week later (I think my dad pulled some strings) he introduced me to the classical guitar.

Maybe one of the reasons it worked out for me so well, was that it was the first really private musical experience I had: because when you’re playing piano in the living room, and there are two professional musicians there, they can’t resist saying “That should be a C sharp!”—even making dinner in the kitchen, I can remember them yelling “Slow that down, it’s too fast!”. And even the ’cello was a known repertoire, and loud, so even if I went into my room it was the same thing.

But the guitar was a complete unknown both to them and to me. The repertoire was obscure, it was out of the mainstream, and it was quiet, so I could shut my door… and I took to it all the time, eight hours a day till I was 17 or 18, just practicing in that room.

So what about the rest of your studies?

Well, I lived near the school, and I was able to condense them into half a day. Any free periods or lunch-breaks I’d spend by walking home and practicing.

Eight hours a day is a lot of time.

I did that consistently. I had a teacher who was really great, called Rolando Valdes Blaine, and he took maybe two students at a time. He would have me for lessons on Saturday, about one o’clock. He’d be pretty much waking up, and I’d be there till five or six at night. With my lessons being so long and me practicing so much, we cruised through a lot of the repertoire.

When it was time for me to go to the conservatory, I studied with Aaron Shearer at the Peabody in Baltimore. But before that, actually, I got my first job as a classical guitarist.

I had done a début concert, and played a few places; but Rolando had been touring with the Joffrey Ballet (which is one of the three biggest companies in the US), and he was tired of going on the road; so he arranged for me to audition and I got the job. I began by touring the West Coast, and got a lot of experience; because the Joffrey would coordinate with local orchestras, such as the San Francisco Symphony. But next fall they invited me to tour the Soviet Union with them, doubling on rock guitar for their rock ballet Trinity. It was quite an experience.

I spent two years with Shearer. During the second year, I was touring in the summer with the Joffrey, and I met my wife Julie here; so I decided to move out, and complete my studies at the San Francisco Conservatory.

[There followed quite an extended discussion of various topics, which, rather arbitrarily, I have decided to lump into the latter part of this interview. But it culminated in a discussion of the repertoire.]

I like the idea of maintaining around 50% of original repertoire in the program—I feel there’s a certain kind of sound and feeling for the instrument that can never be quite be replaced by transcriptions. And modern music often fits the bill.

Such as?

There are so many things that are lined up, waiting to be played: Takemitsu’s Folias, and I understand he’s writing a new piece for Bream. Maxwell Davies I think is a knockout, and I did the US première of his Hill Runes, in San Luis Obispo—I’m going to do that again. Also his Farewell to Stromness.

I’ve played those pieces for friends, and I’ve played them for composers, and they’ll say that they don’t like them, but Hill Runes is an extraordinary piece; and I haven’t quite gotten it yet, in terms of how I’m going to deliver it to audiences and make it work. But I know that it’s got great quality, and I think it’s going to go over well: it’s the most incredible alien landscape, it really sounds to me as if it’s written in Orkney, some place that’s away from everything and full of stone, just an unknown thing.

I really appreciate it when someone finds sounds like that which are not clichés, and that’s an example of the diversity that the guitar can contain—have you ever heard a piece that sounds like that? And that’s the thing that attracts me to modern music, the very sound.

When I started working on Royal Winter Music, I would travel around with that score and just play chords and sounds from it, and I couldn’t believe the quality, the aura of the sound—that’s really what got me interested in it.

Was the attraction of Hill Runes immediate, or did you get into it as you studied it?

It’s been a maze, I would say. Immediately, I liked it quite bit; then I felt I got lost with it. I think part of the thing is, you have to have full conviction in a piece to play it. Now it excites my imagination again. You can feel the quality of a piece but not identify with it, and so sometimes you just have to live with that and let it grow, just spend time.

A lot of time I have music around for years that I’m just thinking about, they’re in there growing somewhere. I’ll pull them out every once in a while, and all of a sudden it’ll be time to expose them to the air.

So that happens with a lot of pieces: one of these is Elliott Carter’s Changes, which was written for David Starobin, and his style can be very difficult to hear. And for some people it’s a very typical modern-sounding style. When I first heard it, I was absolutely thrilled by the piece. It hasn’t been tough for me to play it but it is now.

And there’s a young American composer called John Anthony Lennon, who wrote a more accessible piece called Another’s Fandango. I like that very much, and I’m playing his chamber piece, Ghost Fires.

How did you become aware of Henze?

I had a pianist friend in college, and we used to sit up late and listen to music all the time. He introduced me to all the modern composers, it was really stimulating. One of them was Henze, and one of the pieces was El Cimarrón—maybe you know it, it’s a chamber piece, one and a half hours long, for guitar, flute, percussion and voice, based on the life of an ex-Cuban slave: it’s in fifteen movements, and it tells the story of his escape from slavery in the Cuban Revolution (the man was 106 years old when they found him and he told the story).

So I was teaching one day (this was about 1980) and the phone rings and a guy says he’s putting together El Cimarrón for a tour, and he would like me to play it. So I did the tour, and I loved the music, it felt like I was part of a jazz band, interacting with the other players.

At that time the Royal Winter Music came out, and I started to play it. It’s one of those pieces which I think is typical of great music: the more you play it and live with it, the more the possibilities become, the more it broadens out. When I played it for him, Henze said it was natural soil for me at this point. And it feels like that, I can just pick it up at any point and play it, there are no barriers, it’s a wonderful feeling.

As I say, one of the things that attracted me to it was the incredible sound world that he created. Have you read the introduction that he wrote, where he says there’s as much possibility in the sound world of the guitar as in a gigantic contemporary orchestra, but one has to pause to notice this? Well, I think music comes from silence, and that piece was brought forth from silence. It’s a great piece.

How did you meet Henze?

Andrew Porter, of New Yorker magazine, heard me play El Cimarrón, and he told Henze about my playing, and I sent Henze some of my reviews of the piece. And when he was here at the Cabrillo Festival in Santa Cruz, I played Royal Winter Music for him.

At the end of the first movement, he talked about the characters, and what he’d been thinking about. And at the end of the second movement, he just said “I want to write a concerto for you”—just like that. And of course, I could hardly finish playing.

But he brought the piece to life even further for me, because he talked about his own inspirations, certain paintings that inspired him in certain movements, and other things you couldn’t know unless you talked to him

So he began to write the Concerto, and it’s called An Eine Aeolsharfe, which is the name of a poem by Edward Mörike. One of the ideas of the Concerto is that the guitar not be amplified [experience has called into question the viability of this, particularly vis à vis the last movement—PM]. It’s for guitar and fifteen instruments, which are quite low, and for the most part quite soft. And the guitar is quite high, at least in the first movement—so high in fact we had to do extensive revision when I met him in New York. He said he wanted to write what he wanted to hear, and then I would deal with it—and I think that’s a good way to go, because I can get a concept of the sound world he’s trying to create and then reduce it, maintaining as much of it as I can.

The last movement (which is the longest, and includes the cadenza) was I think done in a greater hurry than the others. The guitar sound, and that of the orchestra, get much bigger, so he wants very big chords—twelve notes. What he intended to show me was the harmonic range he wanted: so of course I reduced them to 5- and 6-note chords, trying to keep the sound as big as possible—I had to do quite a bit of adjusting in there.

The changes I made were mostly in the first and fourth movements—the second and third (in which the guitar purposely has a smaller sound) I kept pretty much the way they were.

Henze is inspired by programmatic situations: so he chose four poems by Edward Mörike, from the early 19th century—very lyrical, very romantic.

The first movement is the title, On an Aeolian Harp. In it, someone is on a balcony overlooking a hillside, remembering having lost a loved one. It’s a gray, wintery landscape in Southern Germany (very near where Henze originates from), and there’s an aeolian harp hanging by this balcony (which is harp excited by the wind). Every time the wind comes up and stirs the harp, it stirs the memory of this young man. Finally, there’s a great gust of wind, and the harp blows around furiously, then some flower-petals fall at his feet.

The second movement is called Question and Answer. There are three verses of poetry, sort of Existential questions being asked, and there are three sections of the music. What Henze did in this was actually set the poetry as if it was being spoken, and then reduce that to the instruments—so it’s almost like a Renaissance piece, an instrumental version of a vocal work.

When we did this in Vienna, he spoke the poetry and I played the guitar. The verses are separated by a solo guitar figure of descending fifths. The third and first sections are similar enough to call a modified ABA form, like a typical second movement.

The third movement is pretty much a Scherzo and Trio kind of feel: it’s the fastest movement, and it has a lot of humor to it. The poem is called To Philomel, and the person is complaining that Philomel is always whining and wanting him to do things. He says “Your lamentations are like a musical scale”— and so there’s a lot of scales! (thirds and sixths, and the guitar sound is getting bigger). There are two main emotive qualities: one represents Philomel, and the other is sweet memories of hanging around with his friends—he really just wants to go to the bar and drink! And there are images of fresh beer overflowing (a duet between the guitar and the harp, a lot of glissandos and arpeggios).

The fourth movement is the most climactic. It begins with a recitative guitar solo, and then a big passage with the guitar and harp together, like one big extended plucked instrument; then a cadenza.

The poem is called To Hermann, and it’s about someone lamenting the leaving of a lover. The cadenza is the time when they’re feeling most alone. The sound becomes very unleashed near the end, and dies away into the same harmonic area as the Concerto began, G Minor, and the guitar and harp play that together over an F# bass, so that it’s unresolved harmonically.

Here’s a loaded question: would you say that the Concerto’s accessible to the average concert-goer?

Well, a lot of people consider the second Royal Winter Music sonata more accessible than the first. I would say it’s more accessible than people’s image of Henze’s music might lead them to expect.

Audiences are very varied: I’ve gone into small towns and played Peter Maxwell Davies, and people have come up to me afterwards and said “Thank you for not treating me like an idiot”.

People are going to have to think for themselves. I would personally be disappointed if guitarists were not interested in a new concerto by an obviously major composer, I would think curiosity would be enough. It’s not going to be the same experience as Rodrigo, but it’s not the same experience as Royal Winter Music either.

[It was during the second part of this interview that news came of the death of Maestro Andrés Segovia.]

Valdes and Shearer were my main teachers, but I went to Segovia’s Master Class. Actually, I was never a great fan of his playing until I spent time with him. He did the auditions for this class while he was on tour, and so I played for him at his hotel in San Francisco, the day after he did a concert here.

Spending about an hour and a half with him in the hotel room, I really got to appreciate was he does and how he does it, to take him on his own terms; and for me that was a big change, I didn’t want him to do anything different to what he did. And I have appreciated him greatly ever since, I think he’s a tremendous player. The thing about him is he has such will to communicate with audiences, and I think that these days, with his technical equipment being less than it was, the willpower is even stronger—you go, and he still gets something across, there’s still that magic that happens.

His version of the Chaconne is still my favorite, I think largely because no one else puts such passion into it.

The Chaconne has such conviction—and that transcription is brilliant, amazing. It was done in pretty much of a vacuum, too—nobody was doing anything like that.

I think the Violin Partitas and Sonatas are a major portion of our quality repertoire, and they’re going to become standard, even more so than now. And I believe they’ll be played more often without basses added—that’s the way I particularly like them.

Yes?

Well, I like them in different ways: if someone plays them well with basses, I can appreciate that. One of the great things about it is that we explore keys that we don’t normally get to explore. And one of the things I like without basses is that it’s musically so exposed (because it’s all single-line stuff) it’s almost more. difficult. Also, the possibilities for different fingerings are greater, so you can almost be more creative.

Do you have a favorite period of music, or a favorite style?

The periods I like best are Baroque and modern. The thing about modern music for me is that my father is a composer; so since I could hear, I’ve been hearing modern music—so it doesn’t scare me or seem strange.

I also love Renaissance music more and more. I’ve done some Milano on my program this year, and I just can’t get enough of that guy’s music. In fact, I have two records coming out: one is Henze’s Royal Winter Music (both Sonatas), and to balance that, a record of lute masterworks—Bach’s 3rd Lute Suite, four Dowland Fantasias and six Milano Fantasies.

I was given a lute: I played some Dowland last year, and a lady came up to me after the concert. She said “I love the way you play, and I have this lute I don’t want around any more, and I’d like to give it to you.”

So I fiddled around with it and played that music, and it’s a really different animal from the guitar.

You can’t hit a lute like you do the guitar, certainly; you have to coax the sound out of it.

Right. But it’s such an instrument of implication, I mean it implies the sustain of the vocal heritage from which it comes. And the guitar can go a little further with that, it can realize some of that vocal implication.

So they’re just very different, and I like the music on both. I know there are guitarists who feel lute music is further away from the guitar than (say) harpsichord music; but I don’t feel that way.

I’m finding that I like more and more music, and I’m constantly amazed at the diversity the instrument can contain—even with so many guitar-players out there, people are creating their own worlds more, carving their own niches and going in different directions. One person becomes known as a South American specialist, another plays a lot of Baroque music, or Romantic, or Modern…

What other guitarists do you admire particularly?

That’s a difficult question. We’ve already mentioned Segovia. I heard John Williams’s concert in San Francisco, and I had not heard him play a whole recital before. I thought it was just phenomenal to hear the guitar played so well, I couldn’t stop smiling the whole way through.

I can’t thank Bream enough for what he’s done for the instrument—if you think about his life’s work, he has explored in depth every phase of the repertoire, and I think that’s great.

I find it interesting with Bream and Williams how they’re always mentioned in the same breath. Because what I find is that they’re almost polar opposites—Williams is more of a classical player and Bream more romantic.

And then the younger generation is amazing; if you turn around every five years the level has jumped way up. There are great young players out there, doing intriguing things. I heard Russell for the first time last summer: he plays beautifully.

Do you have a particular orientation in planning your concerts, chronological or otherwise?

First of all, I plan them around the pieces that I want to play. I think there is some merit in the chronological thing, in the sense that the sound really appears to open up, as the range of the period does.

When you’re dealing with an instrument that has limited dynamic range, the idea of variety is a good one; and lately, especially, I’ve tried to get as many periods in there as possible—in fact, in quite a few programs, I’ve had something from every period.

I generally like to have the heaviest piece, often the longest piece, before the intermission—something pianists often do. There’ll almost always be a Bach piece on my program. I try to prepare those Bach things and live with them for a couple of years before I play them. I nearly always play modern pieces too

What are your favorite pieces, then?

As I say, I really like the Bach repertoire, and I’m working my way through it: in California in ’83, I played the four Lute Suites in a single concert, just because the Society wanted me to.

And then I’ve been doing the Violin Sonatas. I felt first of all that the Sonatas work better than the Partitas, because they have the Fugues, and they’re thicker. But I’ll get to do the Partitas.

I’ve been exploring the Renaissance repertoire. I like to begin with it, because when I get out there I like to play music that feels very vocal, and I can really phrase—sometimes I over-phrase, I feel that’s a way for me to get involved in the music: because if I get nervous, I can become inhibited and tight, so taking music where I can really make it sing helps me to get going. (I’ll never forget, I coached with a pianist named Jeanne Stark, and she said: “When you’re playing well, you move around—and when you’re playing less than well, you sit in one place”).

We were saying earlier that the hallmark of great music is perhaps that you’re always discovering new things in it, no matter how long you listen. Mozart had the idea of writing music that could be appreciated on any level; so the most simple person could enjoy it, but the more you knew, the more you got out of it. I think Henze’s Concerto’s like that: it’s essential for the listeners that the poetry be published in the program notes, which it always has been. As is typical with Henze, there are many hidden (almost private) references—for instance in Ophelia (from the Royal Winter Music), there’s a quote from Mozart’s Jupiter Symphony, which you might not hear unless you knew in advance. I don’t think it’s essential to know all these things to get any appreciation of a piece, but by the same token, if you hear the piece you want to know more about it.

Further Information

David’s website, which includes a discography.