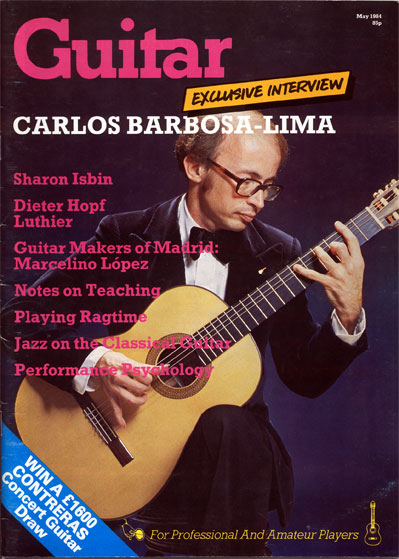

Carlos Barbosa-Lima

interviewed in 1984

Born in 1944, the Brazilian guitarist Carlos Barbosa-Lima (a child prodigy) has been on the concert scene a fair amount of time. Recently, however, he has made a special impact through his adventurous and imaginative arrangements of music by Brazilian and American popular composers: two records have so far appeared, one of music by Antonio Carlos Jobim and George Gershwin, the other of music by Scott Joplin. Shortly before his Queen Elizabeth Hall concert showcasing these and other arrangements, I took the opportunity of asking him about his career, his music, his views, and in particular the Sonata by Ginastera, which is dedicated to him and which he premièred.

I started with music at a very early age: my parents used to tell me that I was very much involved in listening to records (78s at that time, of course) of all kinds of music. They were always listening to good music, it could be classical, Brazilian or American. So I tended to separate records by style of music, or something like that—I was maybe two or three years old.

But my start on the guitar was more or less accidental, although maybe things led to that. My father wanted to take a few lessons, just to entertain himself in his spare time, and he got a teacher near our house. He didn’t really make much progress, for six or eight months (I was about six years old at that time). Now, during those months I became very fascinated by the guitar; and from what my parents said, I was picking up the lessons by watching my father’s lessons. Then my father spotted me one day actually playing, doing what he was supposed to learn and couldn’t really manage. So anyway, he gave up. But he said to the teacher, we are continuing with him, because he is very much interested. So that was my start.

At that time I was already beginning my other studies. As far as I can remember, the guitar became not only a serious study but a pleasure, I really enjoyed the time I had the instrument with me. It was not really a very formal type of education at first, I was just picking up whatever interested me. Then a few months later my father brought someone to teach me basic theory.

I was apparently making pretty fast progress: by the time I was nine I was already playing pretty advanced pieces, but of course with all sorts of faults. Then I was in a music store with my father in São Paulo and the Brazilian guitarist Luiz Bonfá was there. The owner of the store asked me to play for Bonfá, who was interested in hearing me. I was nervous and did all sorts of wrong things, but Bonfá was impressed and predicted that I could succeed in the world of music eventually, and he recommended that I go right away to study with Isaías Sávio, who eventually became my principal teacher.

That was a very, very important turning-point in my life, because not only did I get some much-needed advice from Bonfá (like letting my nails grow a bit, and certain technical things), but right away my father took me to study with Sávio. Sávio was a very encouraging person, because he asked me “Do you really want to be a professional guitarist? Because you can be!”. And I said “Yes, I want it very much.” I remember that moment very clearly.

So it was like making a decision. I started having lessons with him then, and also other music training, but privately: because in those days there were few conservatories. But Sávio thought that since my progress was fast, maybe unique in some aspects, I should have private coaching, and I was very lucky to get wonderful musicians who took a personal interest. One of the important people who took part was Santórsola, the Uruguayan composer, so I was very much encouraged. But I never went to music college, because of the circumstances.

I started studying with a composer in São Paolo right after my début (which was when I was about twelve): this was Theodoro Nogueira, a marvellous musician. He was very influential in giving me the basic foundations of harmony and counterpoint, and he introduced me to arranging music, too.

Later, when I was about fourteen, Sávio introduced me to a work of Santórsola’s, Concertino for Guitar and Orchestra. He came to São Paulo, and he was curious to see me play: because apparently it’s a difficult work, and actually I was going to première it there. He took a personal interest every time he came to São Paulo (he still lives in Montevideo), and would coach me, work on interpretation, harmony, counterpoint, etc.

I am very grateful to these musicians, especially for the broadened view of music they gave me, you know sometimes musicians tend to be very narrow-minded. I remember one time I went to a school for lessons in harmony. It’s funny, because I had very little knowledge of theory: I just used to listen to tunes on the radio and work out the chords on the guitar. So I went to this school and I didn’t understand a single thing, although I was pretty good at other subjects [laughs]. Now I know why: because they tried to do so much through negative aspects: you know, you can’t do this, you can’t do that, instead of encouraging the good things and then saying what you can’t do.

But I became interested in all kinds of music, I think because of Sávio’s attitude. He was the first important teacher who brought the serious study of the guitar to Brazil, and he was very interested in Brazilian popular music, which is very sophisticated.

And of course it’s always featured the guitar to a large extent. That must have been about the time Bonfá was very popular?

Yes, and Bonfá studied with him, too. You know, Bonfá brought another level of guitar-playing to popular music; that was a very important thing. And Garoto, another important player of those days…

Almeida as well.

Almeida, yes, he’s another example. In fact, my father was a big fan of Laurindo Almeida: it was one of the reasons he started. And almost simultaneously there was Luiz Bonfá playing on the radio there, Brazilian but also a little American music, in a tasteful way. My father always said that was why he first bought the guitar, even before he became acquainted with Segovia.

When did you first hear Segovia?

I think it was at the time of the last visit he made to Brazil, about ’56 or ’57, I’ve forgotten now. I was already studying with Sávio, and my whole family was spending a vacation at the beach. My father had to go back to São Paolo to work, and he saw it announced that Segovia was going to play, so he became very excited. We had already bought a few LPs and started listening to them about the same time as Bonfá’s and Almeida’s, so it was an important event for us.

Did you play any of the modern repertory at that time? Santórsola, for example, is best known for pretty modern music.

I’ll tell you how I started. My introduction to the classical repertory was actually before I met Sávio: I was already playing the Fugue from the 1st Violin Sonata of Bach, some Tárrega studies, that sort of thing. But Sávio introduced me to Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Ponce, Moreno Torroba, Villa-Lobos, all that repertory that was blossoming… and simultaneously to the music of Antonio Lauro, I think I was the first one to play that in Brazil. Barrios of course was very popular. Sávio had already written some pieces in the Brazilian spirit, like his Batucada, which I’m playing now. My father was also a fan of good jazz: Duke Ellington, Gershwin’s music, it was very much played down there. Maybe that feeling stays with you and at some point it might blossom. My first concerts were oriented towards the classical literature of course, the Segovia editions especially, which were the first ones to arrive there, and also the Villa-Lobos things. But Sávio was very fond of having some good original Brazilian pieces, so he really introduced me to that philosophy.

Do you still play music by Garoto and the others?

For a few years I kept some pieces in my repertoire, but I wanted to make some good arrangements and add my own style to something they had invented. I was waiting, really. I wanted to do this in the early ’70s, but somehow I thought that the right moment would come with more experience. I have a definite philosophy of harmonising, you know, I like the contrapuntal ideas that are very much a part of Brazilian music, especially the instrumental playing.

These sounds are very much in my head; and so recently, when I started doing these arrangements, I knew where I was going. Even so, to arrange something of Bonfá’s is very hard, because everything is already done, and inventively too. But Bonfá himself was very excited by the idea, because he saw another dimension, a dimension of adding. He has already a marvellous harmonic structure, but sometimes I move the voices, invert the harmonies (thanks to some other influences, maybe Llobet and Segovia). Here and there I add a beautiful effect and special colour, and also expansion towards higher pitch. But this idea came out very clearly in the last three years: that I wanted to incorporate the pieces into my repertoire, but with some touch of my own.

And the welcome has been absolutely wonderful. Even people like Antonio Carlos Jobim, you know… Jobim is a tremendous musician, the man who really changed the direction of Brazilian music, and he knows the guitar too. But when I showed him what I wanted he became fascinated, and he cooperated with me in these arrangements.

And I wanted eventually to incorporate other composers. One that I have been introducing lately had a tremendous part in establishing the direction of Brazilian music, Pixinguinha (that’s not his real name, which was Alfredo Viana). I’m playing him in my concert here. He used to play with Laurindo Almeida, when Laurindo was a very young man. He established several directions, in chôros especially, sambas and other forms, city music primarily, incorporating the Afro element. Maybe a combination of what Scott Joplin did in the United States and Duke Ellington, maybe Gershwin… that idea of making the popular music very sophisticated, the arrangements especially. He was a great arranger, and a marvellous flautist.

Then he met Louis Armstrong in Europe, and became so excited with the saxophone that he introduced it into Brazilian music. I heard him when I was twelve or thirteen, he was on the television, and I was also playing. He heard me, and encouraged me very much. So the music of Pixinguinha is something that I want very much to promote, and my arrangements are exactly recording the ambience of the regional, which is the Brazilian ensemble; you have flute, guitar, bass, you can jam in other instruments too if you wish, it’s really wonderful.

So I have done a lot of arrangements of Pixinguinha and Bonfá, and also Pernambuco’s music, he has some marvellous things. And I have found the greatest welcome among those composers themselves.

How much of all this have you recorded?

I recorded two albums in Brazil in the early ’60s, one of Catullo’s music, and one of Brazilian traditional songs called morhinhas. But recently I started doing American music, composers like Gershwin, Cole Porter, Rodgers, Duke Ellington, and nowadays Sondheim, giants of American music.

I had approached a few companies, but some are very old fashioned, and it’s difficult to do something new. But then I was in Washington DC and played with my good friend Charlie Byrd in his club, and it was very successful. Charlie heard some of my arrangements, things that were not yet published, by Pixinguinha, Jobim and so on. I said that I always believe in what I do, I don’t like just to go and do anything the producers want. Then Charlie suggested that I should record for Concord, which is a very successful jazz label, because they had just started a classical branch. He introduced me to Carl Jefferson, the President, and he was very excited by what I was doing. Right away we made a nice agreement, and he actually asked me what I wanted to record.So I did the Jobim/Gershwin record, and it was so successful. As soon as it came out it started being played on all kinds of radio stations, classical as well as jazz… you know, it’s not a jazz record, I’m using jazz elements but I’m really elaborating on top of that. Although I’m very fond of jazz, what I’m doing is crossing those barriers.

Then when I was working with Jobim in New York a couple of years ago, he called Bonfá in Rio de Janeiro. I hadn’t seen Bonfá in years, but he said he was going to be in New York in the coming summer, so we met and the ideas started developing from there.

With my version of his Manhã de Carnaval, I was very much inspired by a recording he did with Don Burrows, a marvellous Australian flautist and saxophonist, about four or five years ago. It’s totally improvised in the studio, and they took it on the first cut, it’s unbelievable. For me, up to now, it’s the most beautiful thing he’s done. So I used all these elements, and of course some of my own ideas, and then I showed it to Bonfá. Actually, he liked that arrangement so much, he didn’t want to touch a single note.

Other pieces we reshaped together, like the Sambolero, (that’s a marvellous piece, you brush the strings a little in the middle while you sing a melody, it’s a very intimate type of work), and the Xango, which I’m playing in my concert. Bonfá said he had once improvised a second part, and he remembered it by heart; he hadn’t played it in twenty years, I never in my life saw someone recall a piece like that. So he helped greatly. And some things are really complete, I can’t really add much. You have to be very tasteful, and not change or add things just on principle. It’s fascinating to work with someone who knows the guitar, and get that interaction of ideas.

Because of the welcome of the Jobim/Gershwin record, I had already done an arrangement of The Entertainer; so I got a proposal to do a whole Joplin record, which was a lovely idea. That led to the Cole Porter one.

You know, Cole Porter was very influential in Brazilian music, all that generation of American composers; there has always been an interaction, especially because of the jazz. And the Afro element is very integrated into Brazilian music.

Especially in Baden Powell’s.

It’s good you mention that, because Baden came to two or three concerts when I was still in my teens. And then of course I went many times when he was playing, and more than once we played together on Brazilian television.

Really?

Oh, yes! Once it was totally unplanned. I was supposed to play a piece of Bach and then a Brazilian piece, I was only sixteen or seventeen. But Baden was doing some of his most beautiful compositions, O Astronauta, Berimbau, all of that… but he studied classical too, he is fond of Early Music, Bach especially.

So we decided, right on the spot, totally improvised, to have Baden accompanying in a Bossa Nova style while I was playing Bach. I think Brazilian TV still has that on tape. But we played two or three times.

Of course, one day I plan to do something with his music too. I’ll have to think about it very much, because it’s so well written.

How many of your records are we going to be able to get over here? I know the Jobim/Gershwin and the Joplin ones are distributed, but what about the others?

They are going to come. I am more interested in this new wave of records I am doing now. I’ve just cut the record of Luiz Bonfá and Cole Porter, which will be released in June or July. It has a very romantic approach, because the music is like that anyway. I want to do a couple of traditional albums too, the Ginastera and a couple of other things, but I have more plans to do records in this direction if I find they are welcome. Jack [Duarte] has been a great encourager of the kind of work I have done, and he has said wonderful things that inspired me to go on, especially about the feeling.

Because it is an elaboration, but really you have to do it like a composition: you have to visualise it in your mind, and then work on the practical aspects and experiment. Its a combination of something I see and plan, and something spontaneous, half improvising really. You know, I do that for myself: I don’t want to go out and mess up playing with jazz musicians who have been doing it all their lives, but I improvise too. It’s very good: if something happens in a concert, you find your way out and nobody will notice.

A problem in this country is knowing what to look for and what to buy. Apart from your own recordings, whom would you recommend European people to listen to, people who want to enjoy and understand Brazilian music?

Well of course, Baden Powell is a must. Luiz Bonfá’s records, like The Brazilian Guitar, which was done in the ’50s, I think that’s a phenomenal record. And Bonfá had another disc for RCA in the ’70s with more impressionistic music—that is very good because it’s another aspect of Brazil. And then his recent recording with Don Burrows.

Another marvellous Brazilian player is Alberto Gismonte, he’s of the recent generation. And some of Laurindo’s records too, I think he is very tasteful in arranging Brazilian music. There’s one that I recommend as a must, called Brazilian Soul, with Charlie Byrd, on the Concord label. That is one of the best recordings of Brazilian music that I have ever heard. Laurindo has done a lot.

Who are your favourite composers in the classical area?

Well, it changes from year to year. Scarlatti and Bach, Handel too. In the Spanish Renaissance, I like Cabezón’s music: for me he is a great master (actually, later on, even Bach adopted some of is patterns). And in English music I like Dowland; and Vivaldi, that Italian school…

In the Romantic era, I have periods of ups and downs with Beethoven, maybe at the moment it’s a bit down. There was a period I was very much hooked on Brahms, not so much at this point… I mean I admire him, that’s another story. Scarlatti’s a taste I developed in my late teens, but I always like Bach. Also American music, for instance Gershwin, and other kinds of contemporary music. I really felt a great affinity when Ginastera wrote his music for me, music with energy and beautiful inventive new sounds, but serving a purpose.

How did you come to be associated with Ginastera in that?

In the ’60s I heard his first Piano Concerto, and I was very excited, especially by the Finale (which by an interesting coincidence has the same spirit as the Sonata, very much in the popular spirit of Argentina, but with interesting sonorities added; but the form of the Sonata recalls a lot of his earlier works).

A friend of mine, Robert Bialek, in Washington DC, owner of the Discount Records chain of stores, had sponsored my first record in the United States, the Scarlatti one, on Westminster. In 1976, he was celebrating 25 years of being in business, so he had commissioned a work from Aaron Copland, I think for flute and orchestra, and then he thought he would like to commission a work for solo guitar. I already had a concert schedule for later that year. Right away I thought of approaching Ginastera, the idea had been in my head since the ’60s. I wanted to get something structurally powerful, like the Piano Concerto and the Piano Sonata; but I also knew that Ginastera integrates the popular element into his music very much, more than other composers.

I approached him and he was very receptive, he knew about me, so I decided to co-sponsor the work, and my fee from the première concert went to the commission, with Robert Bialek sponsoring the first part.

When I saw the score I got really frightened, because he only finished it a month and a half before the première, and then only two movements. The fourth movement arrived only two weeks before, and I said “Well, I’m going to pray now!”. But I knew exactly what he wanted. So I improvised a little bit for the première, because some things were really unplayable, and I had to rearrange them; he gave me the freedom to do that, and really it came out pretty faithful to his original idea.

The world première got a fantastic review in the Washington Post, and Ginastera then invited me to give the European première in Geneva, in May ’77. He was present, and I was delighted when he not only liked most of the things that I did, he encouraged me to do even more adaptation to make the piece guitaristic. Actually, I think he did a very good job in terms of understanding the guitar in the first place. Because he isn’t a guitarist; of course, he made a drawing of the fingerboard, which is a marvellous drawing except that he forgot that you hit the body of the guitar at the twelfth fret, you can’t do a barré after that.

Anyway, we did some interesting work together, Ginastera was such an encouragement to me, I mean a musician of his stature—for instance, when we worked on the last movement. Of course, I knew that style of Argentine popular playing (you play the Malambo like that, you beat with your hand and then brush the strings like a rasgueado, it’s a very sophisticated style), but at one point, I remember, because of the composer’s being present, I was a bit worried if it was a right chord here and there. And then he said that, especially in the last movement, I should basically follow what he wrote, but there was room to add and do some things with the music, and arrange.

So we started working together. The second movement had a lot of things to change. And then he developed a beautiful canto melody for the third movement, it was amazing hw he imagined so many new sonorities. Then he gave me his best advice for the last movement, which right away I understood: he said: “There you have to penetrate into another world, it’s a jungle, it’s the roughness sometimes, but very strong rhythmically. The notes are not the most important thing, but the sound that comes out”. So with that feeling, and also the different rhythms, I think that is probably the most inventive movement in the Sonata, the last one.

There are some avant garde things in the second movement, but it’s behind a very strong rhythm, so for a general audience it’s not that difficult—even people like my father. He found contemporary music very difficult at first, but he liked the Sonata, because there were a lot of contrasts of sound. And this is what I feel is lacking in a lot of contemporary music written for guitar, some of it is very beautiful, but the sound is very unvaried and monotonous; and then it tends to be a drag. It’s like someone giving a beautiful lecture and the listeners falling asleep; you have to communicate. This is what Ginastera felt too when he wrote the Sonata, he wanted to add as much contrast as he could. So a work like his is not really easy for some audiences, yet you can play it in many circumstances, and I think he was very intelligent in that sense.

Now for me it was an interesting challenge, and also a turning-point, because I was able to get in touch with another aspect of South American culture: Ginastera integrated many different styles. But after that, I decided I needed a really strong change of pace; because you know that work took two or three years. I see people getting anxious to record it, but I think the more you mature, the better it’s going to be, And my attention started transferring into other areas, because I wanted to reach a bigger audience, and to broaden the audience. You have to communicate with people, or music becomes very selfish. So I have several other records I’m going to cut, and then I’ll do the Sonata. Ginastera was for it.

I’ve told Stewart Pope, President of Boosey & Hawkes in New York, that if he liked I could leave it for other people to record, but that when Ginastera was alive he wanted me to do it. I intend to cut the Sonata sometime soon, but I know there has been a mess lately; because apparently, although of course I still have in the contract the option to do the first record, somebody recorded it before me Germany, and Boosey & Hawkes stopped the record. Now, to my surprise, somebody else has recorded it in Italy. I’m surprised because there is a practice now that when you record a piece, you see its publishers about the copyright, and Boosey & Hawkes never got a letter about it. I know that someone in England wanted to do it, and they sent a letter.

So this is a mess, and I feel that after this point I may have a meeting with the people in New York, and just let these people record—I will do my own version anyway, people know it was written for me. I have another plan in my head too, because Ginastera had asked me to transcribe for guitar a very beautiful cycle of Argentine songs for voice and piano that has been very successful. So I may take a little more time and cut a whole Ginastera record, and maybe that will be a nice tribute. This is a decision I’ve been making in the last few days. I could have recorded the Sonata before, but I think maturity brings more things to the music, and one more year will bring me some new ideas there.

What other Ginastera works do you have in your repertoire?

I haven’t played them in public yet, but I transcribed two pieces from his Suite de Danzas Criollas, and it worked beautifully, although I don’t think the whole suite would work. One of them is a big challenge: when I record it, people are going to think I double-tracked, because it’s very contrapuntal. It’s beautiful, in Ginastera’s early style, very romantic.

What else will you be doing in the future?

I will be collaborating with Jobim. We are in the process of commissioning a work for guitar and orchestra, we have a sponsor in the United States. And there is an American composer called Ivana Themmen, who is very excited about writing a piece for me, she was very much taken by these new elements that I have applied. She wrote a concerto for Sharon Isbin; I like her style.

A final question, one I often ask: what advice would you give young up-and-coming guitarists?

Make music a joy and part of your life, not just a career goal.

Discography

| Year | Title | Label | Media | Download | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1982 | Music of Antonio Carlos Jobim & George Gershwin | Concord | Buy CD | ? | |

| 1983 | The Entertainer and Selected Works by Scott Joplin | Concord | Buy CD | ? | |

| 1984 | Music of Luiz Bonfá & Cole Porter | Concord | Buy CD | ? | |

| 1985 | Impressions | Concord | Buy CD | ? | |

| 1987 | Brazil, with Love | Concord | Buy CD | ? | With Sharon Isbin |

| 1988 | Rhapsody in Blue/West Side Story | Concord | Buy CD | ? | With Sharon Isbin |

| 1989 | Music of the Brazilian Masters | Concord Picante | Buy CD | Buy MP3 | With Laurindo Almeida & Charlie Byrd |

| 1991 | Music of the Americas | Concord Picante | Buy CD | ? | |

| 1991 | Chants for the Chief | Concord Picante | Buy CD | ? | With Thiago de Mello |

| 1993 | Ginastera’s Sonata | Concord Jazz | Buy CD | ? | |

| 1995 | Twilight in Rio | Concord | Buy CD | ? | |

| 1996 | From Yesterday to Penny Lane | Concord | Buy CD | ? | |

| 1997 | O Boto | Concord | Buy CD | ? | |

| 2001 | Mambo Nº 5 | Khaeon | Buy CD | ? | With Eddie Gómez |

| 2003 | Natalia | Khaeon | Buy CD | ? | |

| 2004 | Frenesi | Zoho | Buy CD | ? | |

| 2004 | Siboney | Zoho | Buy CD | Buy MP3 | |

| 2006 | Favorite Solos | Mel Bay | Buy DVD | ? | |

| 2006 | Carioca | Zoho | Buy CD | Buy MP3 | |

| 2007 | Alma y Corazón | On | Buy CD | Buy MP3 | With Berta Rojas |

| 2009 | Merengue | Zoho | Buy CD | Buy MP3 | |

| 2013 | Leo Brouwer: Beatlerianas | Zoho | Buy CD | ? | |

| 2015 | The Chantecler Sessions Vol. 1, 1958–1959 | Zoho | Buy CD | ? | |

| 2016 | The Chantecler Sessions Vol. 2, 1960–1962 | Zoho | Buy CD | ? | |

| 2016 | Plays Mason Williams | Zoho | Buy CD | Buy MP3 | |

| 2019 | Delicado | Zoho | Buy CD | Buy MP3 | |

| 2021 | Manisero | Zoho | Buy CD | ? | With Johannes Tonio Kreusch |