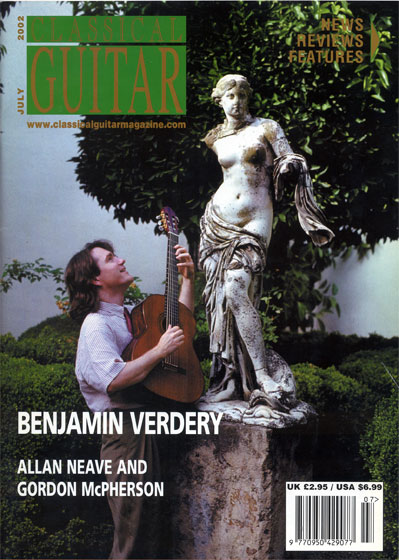

Benjamin Verdery

interviewed in 2002

I don’t recall when and where I first met Ben Verdery, but it was a long time ago. I really got to know him at Paco Peña’s annual Guitar festival in Córdoba, where he taught for several years.

Ben’s classes are markedly different from the conventional ones I remember, for much of the time is spent laughing: Ben is an extrovert and a natural comedian and mimic. But that is not to say that he tells jokes or rambles on off-topic: rather, he has an informal approach that I found extremely refreshing, and I was not alone. One young pupil (who is now a Professor of Guitar) told me that Ben was the best teacher he had ever known—“Nothing is too much trouble, and he has no ‘office hours’ (no tiene horas)”.

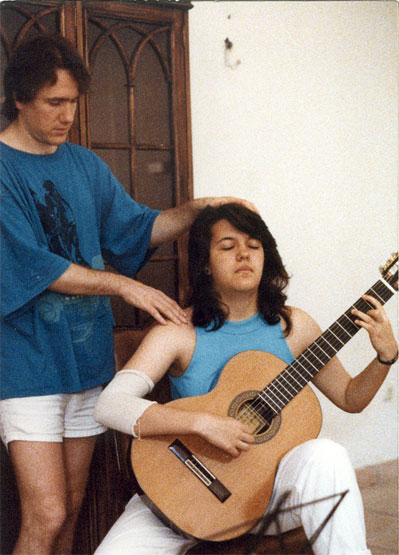

One of the virtues of laughing is that it’s impossible to be tense while doing it, and relaxation and proper breathing are among the primary objectives of Ben’s teaching. One time he brought in a device (with a ping pong ball) that is used in hospitals to treat burn victims, and asked the pupils to play scales before and after breathing into it; the results were quite startling.

Another topic Ben covers that is often omitted, is presentation. I remember on one occasion he was describing all the different approaches to this, and gave a hilarious series of imitations of everyone from Segovia to B.B. King (for the latter, see photograph below).

Ben’s musical taste is extremely eclectic, ranging from music composed centuries ago to days ago, and from jazz to rock music (among his favourites are Jimi Hendrix, The Police and Prince). This is reflected in his recordings, which have included several premières.

Ben Verdery has performed and taught masterclasses throughout Europe, Mexico, Canada, Cuba, Japan and South America, and has recorded and performed with such diverse artists as Frederic Hand, Leo Kottke, Anthony Newman, Jessye Norman, Paco Peña, Hermann Prey and John Williams. He regularly gives flute and guitar concerts with the Schmidt/Verdery Duo and with his ensemble Ufonia.

Workshop Arts has published the solo works from his recording Some Towns and Cities. The recording of the same title includes fifteen original compositions, and won the 1992 Best Classical Guitar Recording in Guitar Player magazine. In 1996, John Williams recorded Ben’s duo version of Capitola, CA for Sony Classical. His Scenes from Ellis Island, for guitar orchestra, has been extensively broadcast and performed at festivals and universities in America, Canada, New Zealand and Europe, and the Los Angeles Guitar Quartet performs it on their CD Air and Ground.

In 1985, Ben became the chair of the Guitar Department at the Yale University School of Music. He lives in New York with his wife (the flautist Rié Schmidt) and their two children.

Recently, he’s been performing with fellow-guitarist William Coulter, under the rubric of Bill and Ben. Somewhat contrary to my expectations, they were both aware of the old British children’s TV series, and quite happy to be referred to as The Flowerpot Men.

Were your parents musicians?

I wouldn’t call my parents overly musical. My mother was an extraordinary wife, mother, cook and hostess. My father was headmaster of the Wooster School in Danbury, CT, an Episcopal minister. He loved to sing in church and knew one student piano piece that had chords, scales and arpeggios in it, which he learned when he was ten. My wife and I would laugh when he played it, which he did well! At age 14, I took up the blues harp, as I was an intense blues geek. He’d criticize me saying that I never played any tunes. One day he said, “Give me that thing” and he proceeded to play Yankee Doodle beautifully with vibrato. I’m not sure Little Walter could have done better! I never looked at him the same after that. So, he had music in him, but he was not a musician but a terrific preacher and public speaker.

How did you get interested in music?

Like thousands, maybe millions of kids in the 60’s, it was the Beatles. I can pretty much pin-point I Saw Her Standing There and I Want to Hold Your Hand. I literally had convulsions and sang all the wrong words. I couldn’t ever understand what Paul was singing, when he sang “and I held her hand in mine” I thought he was saying “And I held her hand in Hawaii”. This was long before I had been to Hawaii!

How did you get interested in the guitar?

I got interested in the guitar because of John Lennon and George Harrison. Now I find Greg Smallman’s guitar is the closest thing I could find that looks and sounds like their guitars! But it’s louder!

How did you get interested in the classical guitar?

I heard the harpsichordist and organist, Anthony Newman play a concert, which consisted of the Italian Concerto, Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue and Book 1 of The Well-Tempered Clavier. My reaction was analogous to the story of the Sea Frog explaining to the Well Frog how big the sea is compared to the well. The Well Frog, me, wouldn’t, couldn’t believe it so the Sea Frog brings him to see the sea for himself and when the Well Frog finally sees it, his head literally explodes. That’s what that concert did for me. I literally no longer had a head! I knew I was not going to play the harpsichord, so I sought out a classical guitar teacher. My mom bought me Julian Bream’s The Classic Guitar album and I fell madly in love with the colors he got. It was the closest thing to Jimi Hendrix that I’d heard. They’re both in love with color, among other things, and it influenced me tremendously.

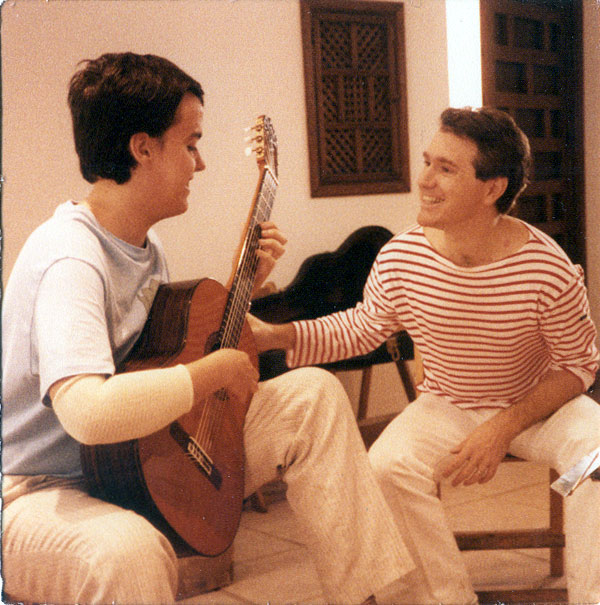

I of course owe a tremendous amount to my teachers, Philip de Fremery and Frederic Hand; also to pianist Seymour Bernstein and harpsichordist/organist Anthony Newman. They had the nasty job of trying to teach me. Fred used to tell me to get no sleep, take three tranquilizers and then maybe I would be teachable. During summers in college, the master classes I took with Leo Brouwer sealed my devotion to classical guitar. He gave me great encouragement at a time when some other teacher might have broken me, I’ll always love him for that. His album Classics of Cuba will always be one of my favorite guitar records

Since my conservatory years, many musicians have taught me so much. Although I never formally studied with John Williams or Paco Peña, I would have to include them among my greatest influences. In general I try hard to maintain a beginner’s mind; it is simply very exciting to be continuously learning.

What is your approach to modern works for the guitar?

The approach is similar to old music. I try especially as I get older, (and I’m quite old!) to study the score. Just read and re-read to let the piece speak to me without me pre-judging it, which is my specialty! Every time I think I know what a piece is about early on, I’m usually wrong. There is always another aspect of it to consider. Little by little, when I understand the musical language, I start fingering passages and consulting with the composer. It’s always exhilarating.

Do you try to fit them into the same programs as more conventional works, or do you prefer to devote entire programs to them?

I rarely play all-new-music concerts. Usually I integrate the old with the new. I tend to agonize over programs I love when I find two to four pieces that I believe work well together. They may be an electronic piece followed by Mozart. At certain guitar festivals, I’ve done all-new-music recitals because it’s so exciting to have such an open, educated audience and I really want people to hear my friends’ music.

How do audiences react to these works?

Different works express different emotions. I enjoy emotional contrasts in a recital. I’m not the best judge of an audience’s reaction. Sometimes I’ll play a new work that’s a bit introspective and judge the audience’s response by the applause. This is a trap. Often someone will come to me afterwards saying how moved they were by such-and-such a piece, and I see how my instincts to play the piece were good. The pieces on Soepa all were audience-tested and I really believe in them as works of art. The title work is one of the most popular new works I’ve played in some time, but I know since I’ve played them all that audiences have been moved by these works and this was the catalyst in recording them. The recording was particularly exciting to make because each composer was present to act as producer for his piece, with the exception of Prince. Those are more arrangements-compositions and I believe he was busy! (I have since found out that he knows I’m playing his music, and I look forward to possibly meeting him.)

Do you feel a responsibility to educate audiences, or merely please them?

I feel a responsibility to tell the truth. In the sense of playing music that I really believe in. There are several pieces in our repertoire which I love teaching but wouldn’t devote my limited time and emotional energy to. Audiences want to know you are committed to a piece 110%. That does not mean that each work has to be as emotionally complex to play as the Bach Chaconne, or Henze’s Royal Winter Music, or that you don't allow yourself performances to grow into a work. It means only that you feel it and want to share it with your audiences.

What is your own approach to composition? What sort of inspiration drives your works?

It varies. I’m about to embark on two different compositional voyages, if you will. Sounds very Spinal Tap! What exactly is a compositional voyage? Should I bring sun-screen? I’m very aware of whom I’m writing for. I try to let go of that because it can be inhibiting.

I’m happy to say I’ve been commissioned to write a guitar orchestra piece for the Tidewater Guitar Orchestra, which uses the terz and bass guitar. I’ve been listening to their CD, getting that sound in my head as a starting point, and familiarizing myself with the instrument. This will be my fourth guitar orchestra piece. The other piece or pieces involve guitar duets.

I’ll be spending a week writing music with Andy Summers. I’m currently listening to his music. He’s recorded 12 CDs since he turned in his badge with the Police, and they’re varied musically. This is interesting because I’m quite emotionally attached to Andy’s sound and musical outlook. Here I’ll sketch things and not finalize anything as I think there will be a lot of co-writing.

I generally have some emotion or theme. On my new CD with Ufonia, each piece has a theme. Several are written for specific people or places, similar to Some Towns and Cities. It’s a great place to start emotionally. At that point, it’s critical for me to decide what the harmonic and rhythmic language will be. It’s always amazing to me that once you start a piece, it begins to write itself. The more I impose certain ideas the worse it seems to sound.

I was asked to write a piece by guitarist Mesut Ozgen, a fabulous professor of guitar and director of the guitar ensemble at UCSC. It started out being a guitar and orchestra piece for eight parts and ended up being for eight or more guitars, two violins, a soprano sax or a wireless electric guitar, and a basketball player. Believe me, I didn’t start out thinking the piece would involve a basketball player, but that’s where the piece took me. The piece is entitled Pick and Roll, which is a play in basketball that I found analogous to a musical suspension. The basketball player comes in at the last quarter of the work and I’ll say no more. The students and the basketball player did a great job.

What is your approach to teaching?

We are all individuals with varying degrees of desires, talent and learning capabilities. At Yale, I teach primarily graduate students, and I’m constantly amazed at how varied their education in undergraduate guitar, and general music studies are. So I give a lengthy interview, helping me to know the students past repertoire, including technical exercises and études, performance experience, and future aspirations. As the beginning lessons unfold I try to become familiar with the student’s strengths and weaknesses, and try and improve both of them

I know several wonderful guitar teachers in America who know what a young aspiring guitarist should study at university level, but simply don’t have the funding to offer all they would envision—I’m speaking mainly about guitar pedagogy, literature and fretboard harmony and intensive chamber music experience. There are schools that do a great job in all these areas and those that simply don’t have the funding. I’m delighted to see how well they do without the additional funding.

How do you feel about conventional approaches to teaching?

I try to reflect each year or two on what a young guitarist should know. I try to have a master plan—a curriculum both undergraduate and graduate. Starting with a structure gives me the freedom to divert from it according to the individual.

Basic understanding of music, technique, chamber music, ensemble playing, sight-reading are essential. A stronger emphasis on fretboard harmony would be welcome. Most of my students who’ve studied jazz guitar have a more secure understanding of the fretboard than those who don’t. Students can practice modes and whole tone, pentatonic scales in addition to their major and minor scales. This will help their sight-reading and they’ll be happier.

Something I address although briefly in my book Easy Classical Guitar Recital (Alfred Publishing)—sorry about the title, some of the pieces are not so easy—is re-evaluating how we learn a piece from the very beginning: how the teacher introduces us to the piece is far too random and casual. In addition, I try to get the student to analyze how he or she practices. One question I’m fond of asking is: “Where is your mind when you're practicing?” So often students practice and simply don’t advance because their goals are too vague and generally too ambitious.

I’m quite concerned about a student’s hands and body working as efficiently as possible. I also want the student to maintain a sense of curiosity, desire, and creativity. More specifically, they should be curious about the form and structure of a work, and have the desire to probe deeper into that piece and be creative in their interpretation. This may mean at times allowing for the fact that they might have a better idea of, for instance, a tempo or dynamic marking of a certain passage than what’s on the page.

In general, I hope to inspire confidence and maintain the sense of joy and discovery they had when they started playing. Life is so short and precious, and there are many psychological traps for students to fall into. They can get burned out, and need to keep their focus on how short their stay in music school is and keep their goals attainable.

That having been said, students need to take more responsibility for their own creativity—so often, laziness sets in. They learn their pieces, go to classes and the year is over. Perhaps each year a student should be required to do some artistic endeavor: either an outreach performance, a composition, recording of something that’s entirely their own and they’ll present it at the end of the year in some fashion. I do these types of projects at Yale in different guises. For example, every other semester my students have to either write an étude or make an arrangement of any given work. I’m pleased to say that many of the students enjoy these projects and some have even had them published.

How do you feel about masterclasses?

I love teaching masterclasses. I try to put the emphasis on “class” and not the “master” part. I like to involve as many people in the class as possible through questions and addressing them as much as I can and not just focusing on the performer. One of the keys for me is creating an atmosphere that relaxes people and helps them enjoy the experience of playing for their peers. It’s wonderful when the class is in a quiet, beautiful room or generally warm environment, for example in someone’s home. That can be beautiful.

I often like to have the students play a little concert before I teach them. This has a few advantages. One is that I can see how I might vary the lessons to make it more interesting for everyone. It also allows the student to perform an entire piece or movement, which they need to do. We all need performance experience, so why not make that formally part of the masterclass?

My wife and I hold an annual class on the island of Maui in Hawaii. Part of the emphasis is on performance and last year we gave two concerts; one at a Buddhist temple, and the other at a small church where you can hear the waves lapping up against a stone wall when you are in the church. All the students perform so beautifully because they’re so inspired by the setting and receptivity of the audience.

Often the amateur guitarists attend the class with scores and ask the most questions. I advocate students coming with scores and a tape recorder. It’s a rare opportunity which some miss by being judgmental. I love to hear my peers teach when they come to Yale. Masterclasses are wonderful events that we often take a little too lightly.

As time is of the essence in masterclasses, different people get different lessons, but it often means what I say to B or C applies to A. If you’ve attended many masterclasses, you’ll know that spending a whole lesson on fingering can be a near-death experience when you are an audience member! When I do see a fingering that frightens me, I try to point it out, show an alternative and move on.

What’s the deal with your Sony recordings? Why are they unavailable? I notice they’re sitting on Michael Chapdelaine’s recordings, too!

Without going into detail, the label I was with—Newport Classic—had three of my recordings: Reverie, Some Towns and Cities and Ride the Wind Horse. These were bought along with many others by Sony. At the time, everyone I knew told me how great it would be to be associated with Sony. Those recordings have been buried in a vault or black hole since 1995. I naively thought that Sony would re-release them, because this is what I was told by someone at Sony.

My advice to any young guitarist is to have an entertainment lawyer advise you before you sign any document pertaining to your career. I didn’t do this and instead took people’s advice on what to do, which was the easy way. I can’t really blame anyone but myself for not taking more time to evaluate that contract. As artists, we get involved in different musical ventures for different reasons. However small a project is, it should be treated seriously because it just may lead to something larger. In fact, one hopes that it does and you want to be legally protected and educated before this.

My last two CDs are, like so many artists’ CDs, self-produced. It’s a great feeling to have complete control. I’ll do the same with my printed music. It’s time-consuming, but I sleep better at night.

I would rather blame myself for a mistake than a record company. The record business is in such disarray that it’s very exciting. I don’t think it’s ever going to settle down to be what it was in the days of LPs. As artists, we will always want to record our chosen repertoire and have people hear it. That’s a given. How we do it, and what form it will take will be constantly changing. In a relatively short time, we have gone from LPs to cassettes to CDs to downloading music. It’s important to be optimistic and realize an artist has more options than ever. There are always going to be companies of some sort for those who want them, and other options for those who don’t. There is no free lunch; you make compromises either way.

Finally, what are your future projects?

After having produced two CDs, one of my own music, Ufonia, and one of my friends’ music, Soepa I’m excited about preparing a new CD of entirely dead German/Austrian composers. It will consist of Bach, Mozart, Strauss and Schubert. In addition, I’ll be writing several new pieces for guitar and other instruments, as well as two new books that I’ll talk about at a later time. We’re obviously living in a violent time, and I feel more than ever, very lucky to play such beautiful music on the guitar. I’m very inspired by all the moving music that’s being written in America and other countries as well. Composers such as Arvo Part, John Adams and countless others, make me very optimistic for the future of music.

Discography

I have omitted the original discography and bibliography, as they can be more advantageously found these days on Ben’s website.