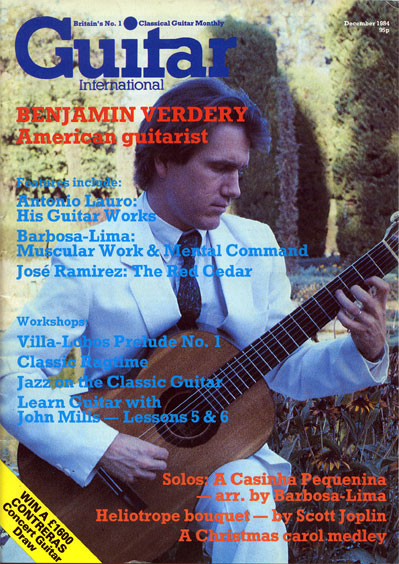

Benjamin Verdery

interviewed in 1984

Two years ago, Ben Verdery was unknown in Europe. Since then he has made his mark in three ways.

The first is his recording of Bach transcriptions ([originally] Sine Qua Non 79040), about which John Duarte wrote (in Guitar, Dec 83) “unquestionably the finest playing of Bach I have ever heard on six strings”.

The second is his playing, both as a soloist and a duettist with his wife, flautist Rié Schmidt, at Paco Peña’s Guitar Festival in Córdoba, in 1983 and ’84.

The third is that he so impressed John Williams that the latter invited him to play duets, first at Paco’s festival this year and subsequently at the Queen Elizabeth Hall.

Ben started playing at the age of nine. Like countless others, he was irresistibly attracted to it by seeing the Beatles in their Famous American début, on the Ed Sullivan Show. He taught himself, and played pop music in various ensembles until he was eighteen, when he became interested in jazz…

…but just as I started to take jazz lessons, I heard a harpsichord concert where somebody played Bach, and I thought it was so wonderful; and I’d been listening to more and more classical music at that time. Also I wanted to go to music school, and I knew I couldn’t do it playing Jimi Hendrix… but that summer I saw a classical guitarist (I wish I could remember his name now), and I was so impressed that I started to take classical lessons. I learned four pieces and that was it, just enough to get me into the Conservatory. I couldn’t sight-read, but I had a wonderful teacher, Phil Defremery, he used to come by my house and spend hours teaching me, because he was working at a college close by and it was on his way home. He’d have a cup of coffee and relax, and he’s play, too; that’s very important when you’re learning, so you can get the sound in your ears, and just observe.

I was four years at the Conservatory, where I studied with Frederick Hand, and again with Phil. In that time I also took three Master Classes, one with Alirio Díaz and two with Leo Brouwer.

I think that what was great, was that there were no other guitarists in my school—at least, it was both good and bad. I was the only one they let in for about two years, so I got to make up my own curriculum. At first I didn’t know what was going on, but then I got some ideas from my teacher, so I was able to play in chamber groups, and so on. It was interesting not to be in a big guitar program, because I always got to be with other musicians and to work with them very closely. That was wonderful. Also, that was where I met Anthony Newman, with whom of course I have a strong musical relationship; and he wrote a marvelous piece for me, and so did other composers on the faculty.

It’s pretty tough in New York, isn’t it? There’s a lot of competition.

There’s an overwhelming number of guitarists, yes. I think I’ve been really lucky. But I was brought up about 1½ hours from New York. So instead of trying to make it entirely in New York, I used to commute out there; because that was where people knew me, and I already had a base there. That helped me out for a year and a half, and I suggest it to all my students: when you get out of school, go where you’re known for a while, teaching and that kind of thing, instead of coming to the Big City where you’re one in a million.

I know classical guitarists in New York who play in restaurants and bars to earn a crust…

Absolutely. And I did that too, I played with Rié. We played restaurants, weddings, you name it. It was just a question of banging on people’s doors, and playing in any situation that you could. I played a lot of chamber music, particularly contemporary works where they showed me a guitar part black with notes, and I said “Sure, I’ll do it”, and I spent the next 28 hours losing my mind, and the piece got performed once… but it still really helped in terms of people getting to hear me. The important thing is to take the job, no matter what it is, and do your best. It helps to be able to put an English sentence together, and to get along with people, and to be able to bend with certain situations… there are necessary aspects too, like a good tape, and a photograph, some kind of résumé which you can make up yourself (or if you can’t write particularly well, have someone do it for you).

What do you think about competitions?

They have a positive side to them, people can hear you play, and it gets you motivated. I only did one, a chamber music competition with my wife, and it turned out to be beneficial, although we didn’t win. I was just on a jury, although I don’t expect ever to be on one again.

But I am basically against competitions, for the simple reason that most people go into them with the wrong attitude; they want to win, which I guess is natural, but it brings out the worst in people. Music can’t be judged like a horse-race. And no matter how fair they think the situation is, it’s not fair, there’s no such thing as fair in a competition. No matter what the system, it usually breaks down. You just can’t expect eight judges with completely different ideas of music to get together and come to a reasonable decision, I don’t know how it can work.

Contestants come up to me and say “What did I do wrong?”. And I can’t answer that. They played heroically, with eight people looking at them, some twiddling their thumbs, some smoking, some with their feet up… they’re given a time-slot and expected to do their best. They may not feel well, they may not have eaten properly, it’s an impossible task. And it has nothing to do with the reality of a concert, nothing.

But surely, the positive side is that when you get a brilliant young player who can do well under those conditions, it brings them immediately to the public attention; if it weren’t for the competition, he’d be just another face in the guitar crowd.

Sure, there are positive aspects. But lots of people who’ve won major competitions have never been heard of again. It doesn’t make a career necessarily: someone who does well in competitions doesn’t always make a great performer. People can win and think “Wow, Carnegie Hall tomorrow”, and that can be a very dangerous attitude.

The other important thing, and the reason I never did a solo competition, is that I never wanted to learn the repertoire. You’ve really got to learn it and love the pieces, and that’s another danger: being forced to learn a piece you don’t really love, and to play it in these conditions, could ruin the piece for you, and give you a bad taste about music. It’s a very delicate thing, because we’re dealing with emotions at the highest level, and under great pressure, and it can be an exasperating experience.

So it can (I’m not saying always) bring out the worst qualities in everybody, because it makes you competitive in an already incredibly competitive world. And my feeling is, if you’re going to do competitions, just watch out. As you say, there’s a lot to be gained, but you’d better see what you’re getting into before you send away for the repertoire list.

Where are you teaching these days?

I’m on the faculties of the Manhattan School of Music, Queen’s College and N.Y.U. In Manhattan I teach ensemble, which is coaching chamber music basically, and that’s a real fun job. And I love to teach privately, too. But now there’s a conflict with all the traveling.

Coming from a Rock background, do you find that students have a narrow attitude towards that music?

No, many of them are involved in Pop music. Today I have two or three that play incredibly well, who play in groups as a sideline. Then they come and play Bach. In America that’s very common.

Do you think it has any effect on their classical playing, for better or worse?

Better, I think: they always have a much more open mind, they’re willing to listen to any kind of classical music. Whereas some people who don’t have that background have fixed ideas in their heads, maybe that they just want to play Baroque music, or… So I find that, if anything, it’s helpful, it just gives them a broader outlook.

Oddly enough, though, I’ve often found that those people don’t like Classical music, I mean Sor, Legnani etc. They love Bach, contemporary music, Spanish music (I mean Albéniz, that era), and pretty much everything else.

Do you ever play arrangements of pop music or jazz or anything?

No. I do it for fun at home, but not on a program; I haven’t found a way to make it work for me, although Jorge [Morel] makes it work for him. For me, pop music on the nylon-strung guitar doesn’t sound real, it’s too much like cocktail music.

Where did you meet Rié?

At the Conservatory, and when she graduated we started out as a duo—I played a lot more duo concerts than solo.

Is repertoire a problem?

I never know how to answer that, it is and it isn’t. There’s actually an enormous amount of repertory out there, it’s just a question of sifting through it. Each year we find new gems, and new ideas for transcriptions, so that I think it’s possible to really put together a wonderful program, combining solos and duets.

Do you have a favorite kind of music? A preference for a period or a particular composer?

I must say I’m a nut for Bach, that’s why I started to play classical music. And if I were on a desert island, I would be more than content to have only his music.

However, there’s no music that I’m not intrigued by, and that I don’t eventually fall in love with: if anything, that’s a potential danger, because there’s so much that I want to do, it drives me nuts. I want to stay here [in Córdoba] and study Flamenco and figure out how it works. I’m now just starting to appreciate, and want to play, Spanish music like Albéniz, Falla and Granados—especially being here, for me it’s so important. I went to Cádiz just because I wanted to play that piece, and of course that’s where Falla’s buried. I can’t wait to get home and learn Córdoba. That whole music area is opening out for me, and I was never really attracted to it before last year. Playing Renaissance music is just starting to interest me, which it never did before. It takes time before you’re ready to play certain pieces. But I’ve always wanted to play Bach and contemporary music, those two things have been very easy for me.

How do you think contemporary music should be presented to an audience?

We shouldn’t put it in a separate category so much. The important thing isn’t that you should play contemporary music for the sake of it, but that you should play music you love—otherwise it’s not going to do anybody any good. I love to play music that someone I now wrote, I think it’s very special, and to me the composer-player relationship has been very positive and unbelievably educational. You play for them, you get their ideas, and you’re involved a lot in the creative process, which is very important.

This is a very exciting time to be a guitarist for that reason, as many people are writing for the guitar now—just this year I’ve heard several really good pieces, that I would play. The problem is that people only tend to play music that was written for them personally, everyone wants his own piece—I understand that, because I’m guilty of it too. But if someone likes a piece that was written for somebody else, they should play it, otherwise we’re never going to build a new repertory. And I still find that, although there are all these fantastic pieces being written, everybody puts his stamp on his piece, so that other people are afraid to play it.

So therefore we have not made the repertory any bigger: it’s still the Nocturnal and the Bagatelles, Leo Brouwer—all great music, but there’s a lot of other music out there. I really do think it’s a danger, people get their piece and they don’t want anyone else to touch it or look at it. That’s understandable for a period of time; if you have new pieces written for you, you should have them for a while. But after that, we have to give them up.

Tell us about Anthony Newman.

He’s been a tremendous force in my life, musically. In America he’s one of the foremost harpsichordists, and certainly the foremost organist. He has countless records available, and is also coming out with a wonderful book called Bach and the Baroque—he’s also quite a Baroque scholar. So all my Bach is studied with him, and his wife Mary Jane, who is also a harpsichordist.

I think what is lacking is composer/performers. One of the reasons that music was (in a sense) so much more vital, I think, maybe a hundred years ago, is that most of the performers were composers—Rachmaninov was really one of the last. So you got great music written for the instrument, and Tony fits that bill. He’s written now two big harpsichord works, a flute and guitar work, and now this duo piece (The Gigue is Up)… solo piano works, trios, every combination. In today’s society everybody wants to be a superstar on their instrument, we’re geared towards that frame of mind, and we’ve lost touch with the creative process that was so vital throughout music history. That’s why people like Leo Brouwer and Anthony are so attractive to me, because they’re doing both. One of the dilemmas of contemporary music is that there’s a gap there never used to be between performer and composer. That’s one of the reasons Pop music is so attractive to me too, why it communicates so well: they’re writing music and playing it, groups like The Police.

So the closest I get to that is playing music by my friends and I really want to compose—I made a promise to one of my teachers this year that I would definitely write a piece, so I’ve got to do it or my name is mud. But also, of course, or standards of performance are now so high that it takes all many people’s life-energy just to play the right notes.

Have you always had a lot of facility?

For me it’s a maniacal thing. just craziness. I love to play fast, and I’m not saying that’s good. I’m slowly learning how to cool down. But I think a lot of it is to do with temperament, your playing reflects your personality, and I’m rather high-strung. I just sat down and played Villa-Lobos’s Study Nº 1 a million times until it sounded right, Sor’s Study Nº 12 (Segovia edition) was another one, hours and hours, and scales still feel that way, I’m a bit of an over-practicer.

How do you use your practice-time?

I don’t have a general daily practice schedule; I have certain pieces that keep everything in shape, and I do those. Practice is the most misunderstood thing among students that I’ve seen. First of all, you have to differentiate between practicing and playing, which most people don’t do: they think that if they play five hours a day, that’s practicing. The important thing is setting up goals for yourself, and they should be small goals, so that when you get up from the chair you’ve accomplished something.

I notice that you play with a cushion to raise the guitar, instead of a footstool, why is that?

I’m very concerned with posture, and for me the footstool creates tension and wastes energy (although I know it works for a lot of fantastic players). It made my hunch over, and I started to take Alexander Technique lessons, which I found very helpful. My teacher showed me this cushion, and I thought it might be interesting, although it looked funny. So I took it home, and the minute I tried it, I knew it was for me. I’ll never forget playing in Córdoba with it last year, and when I came out with it everyone giggled… It’s not macho, I realize that it looks ridiculous [laughs]. But it’s wonderful for me: it takes about two weeks to get used to, and the main thing is that your back is very straight, and you have two feet planted on the floor. It frees my neck tremendously, and that’s a really bad place for tension with guitarists: if your body’s in the correct position, you can learn to breathe properly, which a lot of people don’t do. I always tell my students “Open your mouth, look like you’re trying to catch flies, but do something”. I have a lot of tricks with my students which seem very silly, like, I’ll take a pencil and make them follow it with their eyes while they’re playing. And it’s amazing the feats they can perform, just by breaking the continual focus on the left hand and freeing the neck.

People feel they have to press down, and pluck, extremely hard; but each year I find myself backing off. You barely need any pressure to press down the strings, and the less you use, the better your sound will be. I really believe that sound comes from the left hand, not just the right. That’s one of the keys of Segovia’s sound, his sense of vibrato is—unbelievable. Students will kill the note, if you press down too hard you actually go out of tune. I always envision an imaginary tunnel between the string and the fretboard, so there’s space for the note to breathe.

We as guitarists all have to realize how little pressure you need. That’s one of the things that’s very evident to me when I watch John [Williams] play, there’s no effort, and that’s a great lesson. Of course, most of us have to start from a place of immense tension, I mean that’s what happened to me, I was so tense that I could barely play. So each year I let up, let up…

What’s it like trying to buy a guitar now in the States? I know the best European guitars are very expensive, but there are several American makers coming up, aren’t there?

Yes. Especially John Gilbert, in Woodside, California, and Thomas Humphrey, in New York. There’s a young man out in Long Island, just starting, that is showing tremendous promise—Patrick Caruso. I’ve just seen his fifth guitar, it’s unbelievable. I think if anything there’s a need to create a good student-model guitar, because most people in conservatory just can’t afford $3,000. There is a need for a $1,500 hand-made guitar.

What are your plans for the future?

I’ll be doing a record of concerti, and hopefully another record, of Spanish music. The flute-and guitar record with Rié should be out soon: that has all French music, Couperin, Coste, Debussy, Ravel and Poulenc.