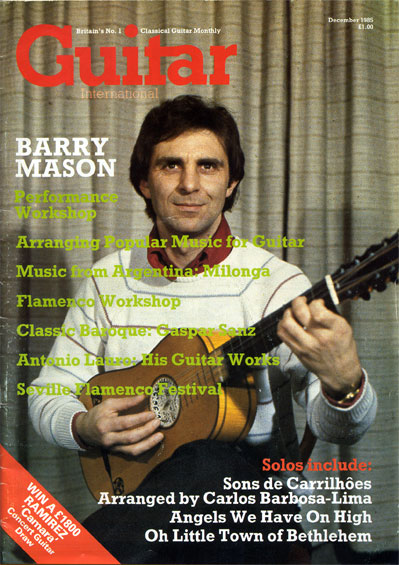

Barry Mason (of The Camerata of London)

interviewed in 1985

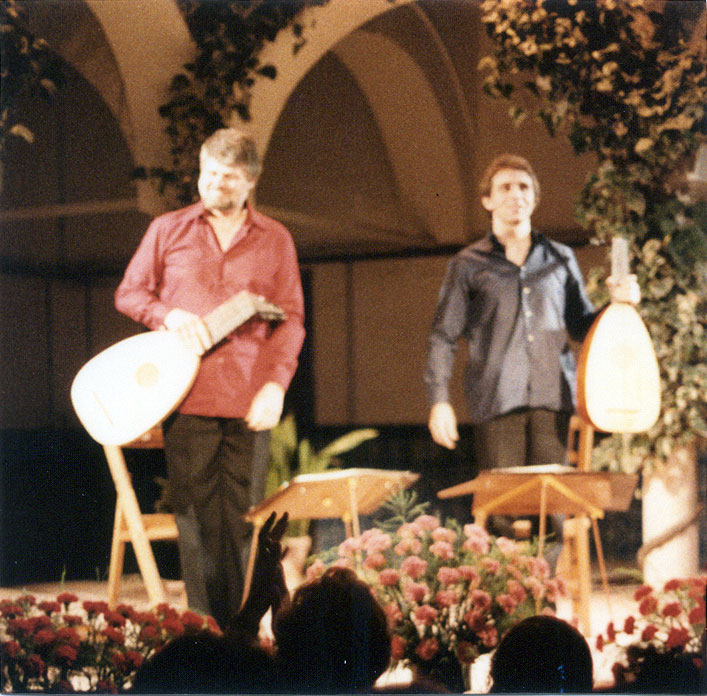

I first met Barry Mason when he was playing merry lute duets with Jim Tyler at Paco Peña’s festival in Córdoba, in 1984. Although we were both members of the Lute Society, we had somehow always managed to miss each other. Subsequently, however, I heard him at a meeting of the Society where he accompanied his wife, singer Glenda Simpson, and we had a lively discussion about modern performances of Early Music, on which Barry holds strong views. Some of these were reflected in his recent article on notes inégales; but he also has much to say about performance in general.

How did you get interested in Early Music, Barry?

Well, I started life as a classical guitarist at the Royal Academy of Music, where I enjoyed my first two years of playing classical guitar. Then I became more interested in the vihuela and lute repertoires; and I thought that to get a better insight into the music I would buy the instruments, and see if the music sounded any different, and whether it made any difference to the technique.

So I had a vihuela and a lute made, and I’ve never looked back. Because when I left the Academy I was taken up as a lute-player, accompanying singers, and got into the Early Music scene as a whole. After a couple of years I started making records with The Camerata of London. We filled the Purcell Room and Wigmore Hall, and arranged a festival in 1977; and things have gone from strength to strength since then.

What instruments do you play these days?

The basic 16th and 17th century plucked instruments which are the lute, vihuela and baroque guitar, using them for solos, accompanying, and continuo in small chamber ensembles (Monteverdi etc.).

The life of someone who plays one of these instruments is very different from that of a solo classical guitarist. The latter spends his time practising music that he’s probably bought, memorising it, then giving concerts around the World. For an early musician there are many more facets: one may spend a lot of time copying music out in the British Museum, or sending off for microfilm to the libraries of France, Italy or Spain. You spend a lot of time learning how to read the tablatures, how to play the appropriate ornaments for different periods, or getting the instructions translated. Then, more practical work is playing continuo in small ensembles, where one has to learn to read figured bass. So one looks to Thomas Mace’s Musick’s Monument for instructions on that. A great deal of my work is taken up accompanying lute singers, so I’m always delving into the works of John Dowland and Thomas Campion. In the past few years, for instance, I’ve made ten or fifteen records. You won’t see me listed on the cover, I’m in amongst the backing musicians; but it’s a very interesting and fruitful experience to do that.

A lot of music from that time is written for unspecified instrumentation; what would make you choose one instrument rather than another? For instance, what is the difference between an archlute, a theorbo and a chitarrone?

Well, each instrument has a definite function—this is becoming clearer and clearer as musicians like myself research into it. One realises how an instrument came about, precisely what it was used for, and where it was used. The lute had 6 courses up to about the middle of the 16th century—e.g. Francesco da Milano is all for 6 courses. Then as the musical language got more complex, it developed, so that when you get to Dowland the music is invariably for 7-course lute, and often for 8-course. Then by 1610 you get an awful lot of music for 10-course lute. The 10-course lute went on for a long time, while these others developed around it.

When we get on to the early 17th century, we know precisely, for instance, how something like the chitarrone developed, in Florence in the 1580s. It developed from the Greek idea of having a solo voice accompanied by a kithara. Of course, they didn’t have any kitharas or lyres in 16th-century Italy, but they did have lute-players; so what they did was develop an instrument with very low octave basses which could make a very wide-octave-span chord. This meant that it could accompany the voice with a very rich texture, and reasonably loud.

The theorbo and the chitarrone are the same thing. They didn’t know what to call it so they named it after the ancient kithara. Then it became know in Italy as the tiorba, which means two heads—i.e. a nut here and a nut there. Then this became anglicised into theorbo.

So this instrument was developing specifically at this time for specific songs, up to about 1640 or 1650. It did have its limitations; when you get on to the time of Purcell and later composers, with their chromaticism, it’s not useful, because it’s too difficult to alter all the bass strings to suit the changing keys.

So one goes back to playing the archlute, which is just a big lute, with added basses. The theorbo’s first two strings are actually an octave down; because they were so long they couldn’t get them up to pitch, so they put them down. It’s got its own distinctive repertoire—in fact it’s the mirror image of the baroque guitar, which puts its bass strings up. It makes these discords (seconds) with the basses. It’s weird, but it’s all quite logical.

And then of course the baroque guitar came up, very quickly. It is interesting how it suddenly swept through Europe. Because music was becoming very homophonic, and it didn’t seem right to strum the lute, it didn’t feel or sound right. Then suddenly you have an instrument that could get a whole chord with rhythm: and in fact the first books printed were music for strumming, with chord-shapes. And a whole new system—alfabeto—was developed to help you strum. It’s rather like chord symbols today, but unfortunately alfabeto B means C, because they started with a cross and then went up B, C etc.… so it’s all one out of step with our common chords nowadays.

You have to understand the whole 17th-century idea of playing the guitar, which is completely different from the modern guitarist’s. Stringing comes into this, stringing the basses with different octaves to create a different sound. Then one has to look at ways of strumming; but it was used not just for this, but in court circles for developing its own technique, completely different from the lute’s or chitarrone’s, with its own distinctive repertoire—for example, the campanillas, fast running, bell-like lines between the 5th string and the top string; also, the baroque guitarists loved discords, so again you can get an interval of a second between the 4th and 2nd strings, sounding very strong, and then resolving to unison. The repertoire is full of these types of gimmicks. Unfortunately, most guitarists have not looked into these problems, and from the beginning of this [the 20th] century, the guitar transcribers have not understood this type of playing at all; so they have transcribed the music as they saw fit, and actually done it completely wrong, so the transcription is only a shadow of the original.

The whole problem of guitarists this half-century is that they have been primarily soloists. That’s fine for those one or two outstanding performers. Inspired by Segovia, they have looked to him for the path of light. But because he was a great solo performer, guitarists have only followed this aspect, and have forgotten the other, peripheral, talents needed to be a musician. The guitar is still looked upon as being out on a limb, and musicologists and colleges of education don’t respect guitarists very much; nor is the guitar an instrument one is asked to join in with. If a guitarist has to go to a recording session, or accompany a singer, he usually falls flat on his face. It’s interesting that these days, some summer schools are asking guitarists to read the bass-line, or join in duets, and I think this is a very good direction. Because ultimately it will allow the guitar to be assimilated into general music-making, which it hasn’t been for very long, long time.

If you go back to the 17thcentury, then it was, because the guitarist then was a “proper” musician: he accompanied the songs, he played with orchestras, he did his solo work—an all-round musician.

Do you think it’s possible to return to that?

I think it’s more possible. The guitar does have its distinctive place in music-making, which is more or less solo repertoire. But if guitarists were taught the proper rudiments of performing music with others, they would get much more work in their fields, such as TV or theatre work; rather than trying to make it as a soloist, which is really only open to a few gifted people at the top.

For every first-rate soloist, there may be ten or twenty B-line people. They shouldn’t be thrown on a heap and told they’re no good—they are capable of performing other duties in the guitar world.

In fact, out of ten guitarists I knew at the Royal Academy, the only one who has made it as a 100% classical guitarist is David Russell (although one or two are making a living with it one way or another, and in fact one is doing quite well as a continuo player).

Even David may go on for five or ten years and find he’s a bit fed up with the whole thing. It’s difficult to know even if we’re training solo guitarists properly: if they’re doing OK now, then fine, but some of the very good ones actually fall by the wayside later. Because after you’ve been doing it for five years, where do you go next?

Music’s supposed to be its own reward, isn’t it?

It is. But if you’ve been constrained by being a solo guitarist, you still come to a problem later on where you haven’t enjoyed playing music with other people. And I feel it would benefit all players and teachers of the guitar if they looked back to their natural heritage. I’m not saying everyone should play early music, but if they knew and learnt about the techniques they would make much better musicians, soloists, accompanists and continuo players.

Certainly you see the same set of faces at each guitar recital, and you never see any of them at an Early Music concert.

Indeed. This is the kind of thing I’m talking about. And another thing I think is very bad—even for the solo guitarists—is that they do not understand a lot about the music pre-Sor. They don’t understand what ornaments they’re using, what ornaments mean, the whole style of 17th-century music. And any violinist, cellist or pianist at the colleges cannot understand why guitarists play the 17th-century music like Villa-Lobos

An exaggeration, surely?

I think it’s true to say that classical guitarists haven’t paid proper attentions to this information even though it’s there; hence the inability to accompany or read continuo.

I’m not saying everyone should rush out now and learn it perfectly. I feel they should be aware of the 17th-century music, know about lute music and tablatures… not necessarily to work hard at it, but at least to understand it—and also play together.

At the moment I’m about a third of the way through writing a tutor on figured bass for guitarists; because all the 17th-century solo guitar books start with a tutor on how to read from the bass line—they don’t tell you anything about how to finger or play the piece, they tell you about figured bass. And that is indicative of the period—the guitarist was an all-round musician who played with others.

But what I find interesting is that 17th-century music is so lively. And it’s something again, that classical guitarists tend to shy away from, that you’ve got to strum this instrument. It had many different flamenco-style patterns—in fact it was called guitarra española by everybody, including the French and Italians.

This is an area of particular interest for you at the moment, isn’t it?

Indeed. I’m doing a lot of work on the baroque guitar, and have got a whole repertoire together. I’m doing a concert at the Wigmore Hall next month, playing a whole spectrum of baroque guitar music—starting with the beginning of the 16th century and ending up with the middle of the 18th. So you have familiar composers such as de Visée, Sanz, Corbetta, and the rarer ones such as Le Cocq, Pelligrini, Granata.

Where do you find all this stuff?

The British Museum is a fantastic storehouse of music. You can handle quite a lot of the original prints of de Visée… nearly all the vihuela composers are there, I remember particularly there’s a lovely Fuenllana print in red and black…

…Then there are fantastic rare manuscripts, especially the music of Weiss—mounds of it—and Santiago de Murcia.

Other sources of music are microfilms, friends like James Tyler, who lends me private books or originals; or nowadays, of course, facsimiles, which are quite expensive, but they’re worth their weight in gold.

You teach using videotape, I believe.

I’m a great believer in using as many techniques as possible to enable the student to learn. So I’ve been using video now for a number of months, in teaching the classical guitar and lute. And I think I’m having quite outstanding results because the pupils not only experience the pressure of camera and lights, they also get accustomed to concert performance. And they see and hear precisely what happens, after each recording. On playback, one doesn’t even have to tell them what is going wrong, they can see it for themselves.

So you see this teaching method in the future, do you?

Definitely. Certainly for musicians who are wanting to be performers or good teachers, then it is necessary to see the whole of yourself perform.

How do you decide the specifics of interpretation?

It’s a very difficult subject, because I’ve these problems all the time, which editions to go by and who was right. I now go back to the original and try and sort through the manuscript, so the difficulty doesn’t arise too much. But I can imagine for guitarists it’s very difficult.

In this respect I’ve got many heroes: musicologists, such as Pujol, who years and years ago, long before anyone knew what the word vihuela meant, published the complete works of the vihuela. They were written out in staff notation, all in odd keys, but, never the less, very useful for the beginner. I played just about every piece Schott published of the vihuela collections, and it’s very difficult to slam those pioneers of previous decades, because they were not to know of the differences from the modern guitar.

I think one’s got to be as cautious as one can and try and get back to the original source as far as possible. There are one or two good editors around. John Duarte, for instance, edits old music properly, but there are ignorant arrangers who arrange the music thinking it is 20th-century music with a 17th-century tune, so they tend to put in idiosyncratic ornaments or slurs which don’t belong there at all.

Do you think modern guitarists could improve the music by, for instance, paying runs with thumb and forefinger?

I don’t think it’s too much of a problem, the style of the right hand, because they obviously used all sorts of fingering anyway. Fuenllana speaks of three different techniques, so I’m sure they used what suited them. I think the idea of style is more important than the old technical problems of fingering.

With dance music, it’s important to understand the background—was it a formal dance, a country dance, what type of ornaments to use—and then play it with whatever technique you have, as stylishly as possible.

For the average guitarist today who wants to find out something about these things, but isn’t a professional—can’t go traipsing around museums, for example—what works could he buy, or get from his library, that would be most informative?

A book to read is James Tyler’s The Early Guitar, which is something you can dip into—if you want to find out about Sanz, for instance, you can look up the chapter on the Spanish school—and that’s a good beginning.

He’s also just recently published a book which might almost be directed at classical guitarists who want to understand the music of the 17th century, called A Brief Tutor for the Guitar. The other thing, of course, is articles in Guitar International magazine. Then there’s a whole range of pamphlets the Lute Society puts out. Diana Poulton’s done one on lute technique, and shortly she’ll be completing a book on the history of the lute, with just about all the facts that are known about it.

Why did you write the article on notes inégales for Guitar International a few months ago? The subsequent correspondence seemed to question your facts.

It was prompted by hearing a classical guitarist playing the D Minor Suite of de Visée at a local concert. Afterwards I spoke to the performer about the interpretation of de Visée’s music. He explained that he didn’t know anything about the French style of playing, and neither did his teacher!

The article was therefore intended as a starting point for those classical guitarists (not baroque guitarists) who would like to approach this subject, and to begin playing baroque pieces with a little more insight. Of course, I am familiar with the wider aspects of this subject, from the instructions of Sancta Maria to Jazz, and I agree with Rafael Benetar, John Duarte and Gérard Rebours and their comments about the difficulties of quantifying the exact note-values of notes inégales. I realise also the generalisations are not as accurate as lengthy essays; but the fact remains that of all the music played by classical guitarists (in concerts or privately), the French Baroque composers come off worst.

We baroque guitarists know most of the facts, but it seems as if it is going to be a long time before we hear classical guitarists playing de Visée in the style of the 17th century, and not à la Villa-Lobos.

Discography

With The Camerata of London

| Year | Title | Vinyl | CD |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1977 | The Muses’ Garden for Delights | Buy LP | ? |

| 1977 | Popular Music From The Time of Queen Elizabeth I | Buy LP | Buy CD |

| 1978 | Music for Kings and Courtiers | Buy LP | Buy CD |

| 1978 | The Queen’s Men | Buy LP | ? |

| 1980 | English Ayres and Duets | Buy LP | Buy CD |

| 1985 | Music of Thomas Campion | Buy LP | ? |

| 1990 | Shakespeare’s Music | ? | Buy CD |

With Glenda Simpson (mezzo soprano)

| Year | Title | Media | Download |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | Now, What Is Love? | Buy CD | ? |

As a soloist

| Year | Title | Media | Download |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | Masters of the Baroque Guitar | Buy CD | ? |