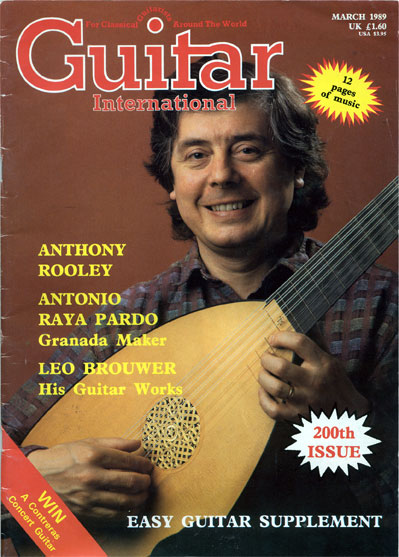

Anthony Rooley (of The Consort of Musicke)

interviewed in 1988

There are not many guitarists who have not been attracted by the music of the Renaissance period: and one of the world’s foremost musicians in that area is Anthony Rooley, lutenist and Director of the Consort of Musicke.

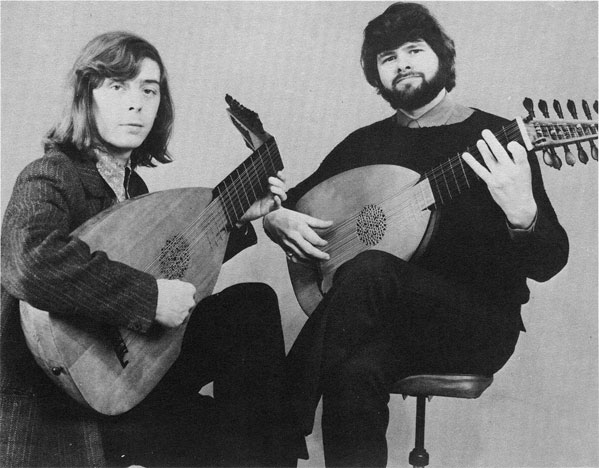

Few people have achieved as much in their chosen field. From early days as a guitarist, a fascination for Early Music led him to switch to lute, and a successful duet partnership with James Tyler (currently of the Julian Bream Consort). I remember their concerts as among those I made it a point never to miss, principally (I think) because of the life they breathed into everything.

Widening his horizons, Tony founded the Consort of Musicke in 1969. Notable in its meteoric rise was Tony’s musical (and subsequently personal) partnership with Emma Kirkby, now regarded as the leading soprano for music of the period. At the time of this interview, Emma had recently given birth to their son, Nicholas, and so was (unfortunately, from my point of view) not with the group, which today is universally regarded as one of the world’s foremost ensembles.

For players, one of the milestones for the less-than-expert was Tony’s contribution to the Music from the Student Repertoire series (Musical New Services); and although (as the interview made clear) Tony is still exploring and expanding his scope into new areas (largely vocal and theatrical), he had much to say about the interpretation of lute music and Early Music in general. But for a start, I asked him about his current activities.

[Laughs] It’s a bit difficult to answer that; a lot of things, it’s a very busy schedule, and I seem to have ended up doing the right thing at the right time—because in the last few years, it’s gone fantastically well.

Just looking at it, since starting the whole business back in ’69, it’s been like a steady rise, and I don’t regard myself as working in Early Music any more.

You don’t?

No, I dropped the term Early Music some time ago; I’m just working in music, full stop. Any label’s far too limiting for the kind of stuff we’re doing, and with the level of performance the group has been achieving over the last few years, I think we should be comparing ourselves with the whole range of chamber music, not just Early Music.

So, I want to specialise in 16th and 17th century repertoire, but I don’t feel I’m part of the Early Music movement any more—I’m doing my own thing within that chosen specialisation.

So are there areas of music which you feel are not within your ambit? Twentieth century music, for example?

Well, in fact we had a fairly lengthy work commissioned, which we performed in the States last year, by Stephen Dodgson, for Emma Kirkby, David Thomas and myself. It’s a terrific piece, it lasts some twenty-seven minutes—we haven’t yet premiered it in England, but we’ve done it three times in the States. And that was an important step.

But I still remain specialising in this 200-year period. I’m opening it up by going deeper in, I’m opening it for everybody else to view, to let them get deeper in, too. That’s quite exciting, and it seems as though it’s working, because (as I say) the diary is full for two years ahead, and we’ve got recording projects stretching for... when I get back to England we just might be clinching a very big sponsorship deal (with a company whose name I can’t mention at this stage). But if it comes off, then we can really spread our wings. And I’ve moved away from seeing myself as a lute player and director of music theatre; because increasingly I’ve been working with large-scale things—fully costumed, choreographed and everything else.

Yes, I remember Cupid and Death a few years ago at the—Q.E.H. was it?

Yes, the English masque of the mid-1650s. And since I did that in London, I’ve done other productions elsewhere, with different numbers of people involved. Last year I did a student production of Psyche at the Darlington Summer School, a massive work by Matthew Locke, runs for three and a half hours, must have 120 people. And I’m finding that sort of thing really very exciting.

So I started out being a little old lute player, and I seem to be moving into all these other things.

Interest in Early Music has been well on the road for thirty or forty years now, even as regards the general public; and the amount of research being done has increased correspondingly.

What do we still not know? What would you like to know about the performance of Early Music that we’re still ignorant of?

I’d like to have even a two-minute recording of a vocal ensemble of around 1600, say from the court of Turin, performing a madrigal of Sigismondo d’India; because I would like to know how mannered the musical performance was, what style of mannerisms were used. I’ve built up a fair catalogue, because I approach his music in a highly manneristic way, which I think is demanded; but I would like to know, by having a brief glimpse of an original performance—which, of course, I’ll never get. And we’ll never get the backing up of literary sources and references to ever be certain.

So there’s an area where I wonder, am I going too far? Or am I not going far enough?

But there are lots of areas that need opening up, that’s just an example.

How concerned are you with authenticity per se?

To the extent that I believe... say in lute-playing: in the age when all that vast repertoire was created, I believe that they were closer to the instrument than we are today. And therefore, whatever they did, and whatever they thought about the instrument and the repertoire, the style, the ornamentation, I would suggest that we’ve something to learn from it. Because it was part of their everyday life, they were living and breathing the thing.

And of course, there was already two or three hundred years of tradition behind it.

Exactly. And exactly the same also for vocal polyphony; writing for five or six voices is such a skill, it needs such craftsmanship even to write a few bars; and I feel they were so attuned to what they were doing, that we must attune ourselves, as best we can, to understand their attitudes to life.

But that’s not the end of the story: because, having done that, I don’t think I’ll ever forget that I’m a man of nineteen-eighty-whatever, I really belong now, so I have to make a transition from an authentic enquiry into a performance that works today.

So, I’m quite prepared to compromise in a number of ways. For instance I don’t intend to travel with gut strings. Because coming off a jet plane in New York, doing a concert, then arriving here in San Francisco the next day—gut strings just don’t stand up to it, they go completely haywire.

Then too, there’s the consideration that there were technical limitations in the instruments and the materials that they were trying to overcome; and so replicate fastidiously every detail of something that they themselves would have improved if they could...

That’s a dangerous one though, because—would they have improved it in the direction that we’ve got? We can’t tell.

If someone had come up to John Dowland and offered him nylon strings, what would his reaction have been?

I don’t know; but if he had been jet travelling, I’m certain he would have taken my decision.

On the other hand, I think it’s important that there are those who are experimenting with every little detail; and I would back them up all the way, and I’m interested in their findings, because there’s always something to learn from that.

So I think that if you’re not locked into an habitual attitude: if you’re prepared to enquire, discover; then you’re in good shape. As soon as you think, “I don’t want to know about that, it’s not for me”, then you’re starting to build a wall around yourself, and you quickly get left behind—not only in terms of getting the bookings coming in, but in terms of awareness, and I want to lead, rather than get left behind.

Guitarists for the last several years have been more careful about playing lute works on the guitar; for example, you don’t just leave the third string tuned up to G, and if you get an F# just leave it out, as often used to be the case.

But then again, you get the question of how far you’re going to take it. Are you going to abstain from using the right hand third finger? Are you going to play runs with the thumb and first? You must have heard performances of lute music on the guitar: how do they strike you?

To be honest, I haven’t heard much lute music on the guitar for a very long time. The reason is, I think, that there’s been an extraordinary explosion of lute-playing in itself, an awful lot of people have taken up the lute in the last... ten years? And, because I’m known as a specialist, and I run workshops and so on, it’s lute players that tend to come along.

I must say that my work’s focus has shifted towards the voice terrifically over the last ten years, and the lute is a supporting role, so I speak a lot about the art of accompaniment.

But occasionally I’ve had people accompany the voice on the guitar. And I give all credit to them. I think it’s better to use any instrument and have the repertoire aired. And in a workshop situation, the guitarist is sitting alongside lutenists also playing; his ears tell him where he should be going next, what his decisions should be. For one person, it might be that he should be taking up the lute; but for another, it confirms that he should be working hard on the guitar.

So I can’t make a general rule, really. I would say that for each individual—and when I’m teaching a student I expect him to develop his own line of enquiry and make his own decisions—the music itself tells you what you should be doing with it.

Tuning the third string down: well, I think that’s a matter of common sense, really, it’s a very small adjustment.

As to plucking techniques: the guitar responds so differently from the lute, that I would say that thumb and finger is hardly appropriate to the tension that a modern classical guitar is under. (If you’re playing a flamenco guitar it’s a big different, because it’s a lighter action, and you can make a case for that.)

But now that I’ve played the lute consistently for nearly twenty years, and hardly touched a modern guitar—when I pick one up I haven’t got the strength in my left hand to hold down a chord; because it’s strung under such tension, and despite the fact that the lute has double the number of strings, or more.

Though I must say that my guitar-playing years gave me a disciplined left hand, which I can use on the lute.

The right hand is a different matter. I see it like this: the classical guitar is made to project, and it’s been developed and constructed—strings as well—to make the loudest sound possible. And I think that concern for dynamic projection has almost overruled everything else; so that your technique has to be really strong, a lot of apoyando and so on.

The lute is quite another matter: it’s so lightly constructed, such a light tension, that if you lay into it like you do on a guitar, the thing just falls apart. It’s the opposite, it’s sort of a retiring mentality, where you draw the listener in, instead of projecting out to him.

And so all the right hand technique is aiming in the opposite direction: one is a meditative approach, the other an attacking approach.

Speaking of the right hand, I notice that most people these days play “thumb under”…

I don’t, I use what I think was Dowland’s technique.

But he changed, didn’t he, from “thumb under” to “thumb over”?

Yes, I think he was responsible for developing thumb and forefinger together, which allows you to go thumb under or over, you’ve got that degree of flexibility. You see, some of his Fantasias are so constructed that you have to have that flexibility, I think.

So I’ve tried to develop a technique as I think the most advanced lute-playing was around 1610. (I’m not interested in getting into the fancy French style of Gaultier and the rest—I like the music when it’s played by somebody else, but it doesn’t have enough in it to hold me.)

I love the repertoire of Francesco da Milano and so on, but I seem to be spending most of my time centred around 1600, with a vocal repertoire. So therefore, the lute music I play is mostly in a supportive role, and I play solos of the period to give the singers a break.

I think my playing technique is a accurate as we can know about … Dowland in his prime … Varietie of Lute Lessons, 1610. It’s not thumb under. Thumb under is, I believe, suitable for music earlier than that: but Dowland’s virtuosity led him to experiment with hand positions. And if you follow the history of lute playing, and you look at pictures from 1500 onwards, and look at the right hand, you have the finger, from almost running parallel with the strings, swinging right the way round to the baroque instrument, with the thumb ever further out than it is on a guitar.

It’s a quadrant, isn’t it that’s described: and you can find the information from iconography from 1500 to 1700, giving you that full span. And I think Dowland, operating right in the middle, is just—sensible. It’s a relaxed hand position, and so on. Oh, we lack a lot of information to be wholly precise, but I have a feeling that what I’m doing is about right.

One of the tenets of lute-playing is that slurs are anachronistic. But some of the cadential ornaments, such as in the Fantasia No. 7 from the Varietie, are almost impossible without using slurs, if you take the piece at normal speed. Would you agree with that?

[Laughs] They’re not really possible for me at the moment because I’m out of practice. But I would disagree, I would prefer to pluck out those cadential figures. It’s in more lyrical passages that I find myself wanting to slur for musical reasons, and a slur is one of the ornaments that a player of any plucked instrument is going to use. But I would use it, not for speed, but for expressive reasons. That’s my opinion, anyway.

You see, I think we’ve got to be careful about the speed thing. Have you heard Paul O’Dette play? He’s the Fastest Lute in the West; and he carries it off. I respect Paul’s playing terrifically, I think he’s one of the best players we have; but, I feel that there needs to be more poetry there. Now, Paul might turn round and say, Rooley’s out of practice, he can’t play fast. Well, I am, OK. But I know poetry when I hear it, and I think that that’s really what moves the heart of the listener, more: it’s how you use the silences, and so on. And that’s done with as much skill, but it’s of a different kind, and it’s a less obvious kind of virtuosity.

So we’re talking here about two very different kinds of personalities—which is as true now as it was then. It’s an authentic problem, but it’s not one that we have written up, at all. So it can never be solved.

But take the question of playing with fingernails, of not (we know for certain that Alessandro Piccinini advocates playing with nails).

There are about six scraps of information on the subject. And this is a ludicrous argument that we’ve got ourselves into, which began in 1975, and got really hot by about 1976 or ’77, when the received opinion became, “You cannot be authentic and play with nails”. Which is absolutely bananas: because of these six shreds of information that can be assembled, three of them say, don’t play with nails because it’s a horrible sound (which shows that somebody did play with nails); one of them says precisely that you should play with nails because you get the best kind of sound; one is ambiguous; and the other says that flesh is more beautiful.

This suggests to me that in the 16th century, some played with nails and some played without.

Now, this isn’t the end of the argument, because it depends on the length and shape of the nail, and how the individual’s finger is constructed. And if you look, everybody’s finger is very different.

What I’ve developed for my playing is something of a compromise. I don’t meet the string with the nail, but I have the nail long enough to support the flesh in front of it; and this gives me an edge of projection which I don’t find with players who work with no nails. It gives focus to the sound.

Is there any part of the repertoire that doesn’t appeal to you?

I think French repertoire doesn’t speak to me at all.

What about the lyrics of some of the madrigals? And all that stuff about Nymphs and Shepherds written by people who wouldn’t have known a sheep if it fell on them?

I don’t like the trite material very much; I think it depends how it’s done. The Consort’s known as I Lamenti in the trade, because we do so many grievously heavy programmes. And that’s fine, I don’t mind that. I’m a cheerful chap, not a depressive—I don’t do melancholy music because I’m a depressive, it actually cheers me up. And the audience’s reaction is the same too.

There are other things I don’t much care for: I find I need to select my sacred music quite carefully. Some of it seems to get quite glutinous, in the wrong sort of way. I do find too much church music gets up my nose, even though it’s superbly crafted.

Are we talking about Palestrina, that sort of thing?

Yes, Palestrina—actually, some sacred pieces of Byrd. There are some stunning, stunning pieces, but there’s lots of wallpaper as well. The latest recording of Josquin by the Tallis Scholars (which won all the prizes last year) is a superb example of sacred music sung with real verve: they take surprisingly fast tempi and really make it work—and to hear those motets really ringing out! Fantastic. So often it’s not so much the repertoire as the attitudes that are gathered round it.

But I find myself increasingly interested in the pagan side of the Renaissance, rather than the Christian side—the love of Plato, and the whole Classical tradition. There was a constant battle between the Greek strand and the Christian strand, and I find orthodoxy really gets up my nose.

Plus of course you’ve got the heavy Arabic influence in Spain.

Well, that’s going earlier than my repertoire. I love medieval music, just as I love Bach (but never play it). I’ve decided to focus between 1500 and 1700, for very clear-cut reasons, I think. I mean, I love a wide range of music. A lot of people think of me as such a specialist that I must be narrow-minded, but I’m not. (I love Indian music, I still listen to a lot of it. There’s a singer, Parveen Sultana, who’s the most phenomenal singer, and I learned so much from listening to her. I listen to Sarah Vaughan.)

Transcriptions are something I’ve really got excited about recently. Because I’m working with voices and planning programmes around vocal repertoire, I find that singers need a rest at some point; but what do I play, on the lute? There’s no music surviving from that period—I’m thinking particularly of England after 1620. I don’t want to get involved in French lute tunings and so forth: it really doesn’t appeal to me, and I don’t play French repertoire anyway.

We do know that Vieux Gaultier was working in England, and a few scraps of manuscripts show use of various French tunings, because French styles were popular. So one could say that I’m shirking the problem. But the repertoire doesn’t go on that far—what can you do when you’re doing a program of Blow and Purcell? You could do Thomas Mace (very dull music); and after that, we have nothing which is specifically English.

So what I’ve started to do recently is transcribe from works which were used as stock material—like Music’s Handmaid, published by Playford, a small suite of dances for the harpsichord. Some of these fit on the lute extremely well. And we know that certain versions did exist for the lute, they just don’t survive now. Then you get a version for cittern (a rather cramped version without a bass line), and a version for solo violin. And if they felt free to mess around with this stock material, then I feel that’s an invitation for me. So I’m working with an authentic repertoire, but adapting it to a playing condition which I like, writing my own divisions or decorations for repeats, and so forth.

When I recorded Renaissance Fantasias, I thought it would be the last solo record I would get around to making, because my attention’s elsewhere; but in the last few months I’ve begun to think that maybe there’s a record for me to make of my own transcriptions.

I don’t go for the idea that to be authentic, you can only play things that have happened to survive by chance—Dowland would have considered that ludicrous in the extreme. I think that the spirit of authenticity is continuing the process of creativity.

Is there not an element of snobbery involved as well? If you can’t be better musically than someone else, at least you can be more authentic?

Oh, that’s certainly true. I could name a number of people in Early Music who’ve taken that position for that very reason.

But I think that’s a long way behind us, you know; that’s why I don’t use the label Early Music any more.

When you discovered Emma, did you have any idea that she’d become what she is, i.e. the leading female singer of Early Music in the world?

Yes, I did, actually. I mean, when I first heard her voice I was just knocked out by it (the fact that I was also knocked out by her is now history). I didn’t know quite how successful she was going to be—she’s really become the voice of this time, because it’s now gone beyond Early Music. People were critical at first, and said “Thin piping, schoolgirl voice”. And even now you get the occasional critic (like Tom Sutcliffe) saying “Must be fed on a diet of plain yogurt”.

But this is far from the truth. If anyone actually listens to how the voice has developed over the last ten ears, it’s quite remarkable. The instrument has become every more focussed, and fuller—a wider amplitude, without losing its clarity.

I think performance is really about this: every time it should have a feeling as though you’re actually composing it in the moment—the skill of the performer is to create it as though it was happening for the first time.

Partial Discography

Tony’s discography, with that of the Consort, was already formidable at the time of this interview; it is now so multifarious as to defy my powers to track. I have therefore reproduced, in the Vinyl section below, the one Tony originally supplied, together with such links as I have been able to find. Below that is a Digital section, with a representative selection of available recordings.

For more information, see the External Links at the bottom of the Consort’s Wikipedia entry.

Vinyl

Anthony Rooley

| Title | Label | ID | Vinyl |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Cozens Lute Book | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 510 | Buy LP |

| Renaissance Fantasias | Hyperion | A66089 | Buy LP |

With James Tyler

| Title | Label | ID | Vinyl |

|---|---|---|---|

| Renaissance Duets | L’Oiseau-Lyre | SOL 325 | Buy LP |

| My Lute Awake | L’Oiseau-Lyre | SOL 336 | Buy LP |

With Emma Kirkby

| Title | Label | ID | Vinyl |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Lady Musick | L’Oiseau-Lyre | D186D4 | Buy LP |

| Olympia’s Lament | Hyperion | A66106 | Buy LP |

| Time Stands Still | Hyperion | A66186 | Buy LP |

With Emma Kirkby et al.

| Title | Label | ID | Vinyl |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amorous Dialogues | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 587 | Buy LP |

| Duetti da camera | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 588 | Buy LP |

| Pastoral Dialogues | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 575 | Buy LP |

With David Thomas

| Title | Label | ID | Vinyl |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gemma Musicale | Hyperion | A66079 | Buy LP |

With The Consort of Musicke

| Title | Label | ID | Vinyl |

|---|---|---|---|

| Byrd: Psalmes, Sonets & Songs | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 596 | Buy LP |

| Byrd: Consort Music | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 599 | Buy LP |

| Coprario: Songs of Mourning, etc. | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 511 | ? |

| Coprario: Funeral Tears, etc. | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 576 | ? |

| Danyel: Lute Songs | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 568 | Buy LP |

| Dowland: First Book of Songs | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 508–9 | Buy LP |

| Dowland: Second Book of Songs | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 528–9 | ? |

| Dowland: Third Book of Songs | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 531–2 | Buy LP |

| Dowland: A Pilgrim’s Solace | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 585–6 | Buy LP |

| Dowland: Mr Henry Noell Lamentations | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 551 | Buy LP |

| Dowland: A Miscellany (instr.) | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 556 | Buy LP |

| Dowland: Lachrimæ (instr.) | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 517 | Buy LP |

| Dowland: Consort Music (instr.) | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 533 | Buy LP |

| Dowland: Complete Lute Music (instr.) | L’Oiseau-Lyre | D 187D 5 | Buy LP |

| Gesualdo: Fifth Book of Madrigals | L’Oiseau-Lyre | 410 128-1 | Buy LP |

| Gibbons: Madrigals & Motets | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 512 | Buy LP |

| Holborne: Pavans & Galliards (instr.) (with the Guildhall Waits) | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 569 | Buy LP |

| d’India: Eighth Book of Madrigals | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSDL 707 | Buy LP |

| Jenkins: Consort Music | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 600 | Buy LP |

| Lassus: Lagrimi di San Petro | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSDL 706 | ? |

| H. Lawes: Psalmes, Ayres & Dialogues | Hyperion | AA66135 | Buy LP |

| W. Lawes: The Viol Consorts (instr.) | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 560 | Buy LP |

| W. Lawes: The Violin Setts (instr.) | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 564 | Buy LP |

| W. Lawes: The Royall Consorts (instr.) | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 573 | Buy LP |

| W. Lawes: Dialogues, Psalms & Elegies | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 574 | Buy LP |

| Maynard: XII Wonders of the World | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 545 | Buy LP |

| Marini: Le Lagrime d’Erminia | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 570 | Buy LP |

| Marini: Violin Sonatas | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 576 | ? |

| Monteverdi: Fourth Book of Madrigals | L’Oiseau-Lyre | 414 1481 | Buy LP |

| Monteverdi: Fifth Book of Madrigals | L’Oiseau-Lyre | 410 291–2 | Buy LP |

| Monteverdi: Madrigal Erotici | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSDL 703 | ? |

| Morley: Ayres & Madrigals | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSDL 708 | Buy LP |

| Notari: Love & Languishment | Hyperion | A66140 | Buy LP |

| Schütz: First Book of Madrigals | Harmonia Mundi | IC067 169 5271 | Buy LP |

| Trombocino: Frottole | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 593 | ? |

| Ward: Madrigals and Fantasias | L’Oiseau-Lyre | D238D2 | Buy LP |

| Wilbye: Madrigals | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 597 | Buy LP |

Anthologies

| Title | Label | ID | Vinyl |

|---|---|---|---|

| Le Chansonnier Codiforme | L’Oiseau-Lyre | D186D4 | Buy LP |

| Lamento d’Arriana | Harmonia Mundi | IC165 1695043 | ? |

| English Madrigals etc. | Hyperion | A66019 | ? |

| Music for the House of Fugger | L’Harmonia Mundi | IC165 1695541/2 | ? |

| A Musical Banquet | L’Oiseau-Lyre | DSLO 555 | Buy LP |

| Musicke of Sundrie Kindes | L’Oiseau-Lyre | 12BB 203–6 | Buy LP |

| The World of Early Music | L’Oiseau-Lyre | SPA 547 | Buy LP |

Digital

Anthony Rooley

| Title | Label | CD | Download |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Cozens Lute Book | L’Oiseau-Lyre | Buy CD | Buy MP3 |

| Renaissance Fantasias | Hyperion | Buy CD | ? |

With James Tyler

With Emma Kirkby

| Title | Label | CD | Download |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Lady Musick | L’Oiseau-Lyre | Buy CD | Buy MP3 |

| Olympia’s Lament | Hyperion | Buy CD | ? |

| Time Stands Still | Hyperion | Buy CD | ? |

With Emma Kirkby et al.

| Title | Label | CD | Download |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amorous Dialogues | L’Oiseau-Lyre | Buy CD | Buy MP3 |

| Duetti da camera | L’Oiseau-Lyre | Buy CD | Buy MP3 |

| Pastoral Dialogues | L’Oiseau-Lyre | Buy CD | Buy MP3 |

| Purcell: Songs & Dialogues | Hyperion | Buy CD | ? |

With The Consort of Musicke

| Title | Label | CD | Download |

|---|---|---|---|

| Byrd: Psalmes, Sonets & Songs | L’Oiseau-Lyre | ? | Buy MP3 |

| Coprario: Songs of Mourning, etc. | L’Oiseau-Lyre | Buy CD | Buy MP3 |

| Danyel: Lute Songs | L’Oiseau-Lyre | Buy CD | Buy MP3 |

| de Rore: Il Quinto Libro Di Madrigali | Musica Oscura | Buy CD | ? |

| Dowland: First Book of Songs | L’Oiseau-Lyre | Buy CD | Buy MP3 |

| Dowland: Second Book of Songs | L’Oiseau-Lyre | Buy CD | Buy MP3 |

| Dowland: Third Book of Songs | L’Oiseau-Lyre | Buy CD | Buy MP3 |

| Dowland: A Pilgrim’s Solace & Mr Henry Noell Lamentations | L’Oiseau-Lyre | Buy CD | Buy MP3 |

| Dowland: Lachrimæ (instr.) | L’Oiseau-Lyre | Buy CD | Buy MP3 |

| Dowland: Honey from the Hive | BIS | Buy SACD | ? |

| Dowland: Earth, Water, Air & Fire | Gaudeamuss | Buy CD | ? |

| Gesualdo: Fifth Book of Madrigals | L’Oiseau-Lyre | Buy CD | Buy MP3 |

| Holborne: Pavans & Galliards (instr.) (with the Guildhall Waits) | L’Oiseau-Lyre | Buy CD | Buy MP3 |

| d’India: Eighth Book of Madrigals | L’Oiseau-Lyre | Buy CD | ? |

| Jenkins: Consort Music | L’Oiseau-Lyre | Buy CD | ? |

| W. Lawes: Dialogues, Psalms & Elegies (instr.) | L’Oiseau-Lyre | Buy CD | ? |

| Monteverdi: Second Book of Madrigals | Virgin Classics | Buy CD | ? |

| Monteverdi: Fourth Book of Madrigals | L’Oiseau-Lyre | Buy CD | ? |

| Monteverdi: Fifth Book of Madrigals | L’Oiseau-Lyre | Buy CD | ? |

| Monteverdi: Sixth Book of Madrigals | Virgin Classics | Buy CD | ? |

| Monteverdi: Eight Book of Madrigals | Virgin Classics | Buy CD | ? |

| Monteverdi: Madrigal Erotici | L’Oiseau-Lyre | Buy CD | ? |

| Monteverdi: Madrigali Guerrieri et Amorosi | Virgin Veritas | Buy CD | ? |

| Morley: Ayres & Madrigals | L’Oiseau-Lyre | Buy CD | ? |

| Porter: Madrigals and Ayres | Musica Oscura | Buy CD | ? |

| Trombocino: Frottole | L’Oiseau-Lyre | Buy CD | ? |